SINGAPORE: Like an anecdote straight from an Alanis Morissette hit, I took leave to catch up on my sleep debt, only to begin writing this commentary.

The irony would be amusing if my inability to switch off wasn’t so problematic that it has resulted in a permanent imprint of burnout on my psyche.

It’s easy to blame the COVID-19 pandemic and its engulfing sense of malaise for burnout, but burnout has existed since time immemorial. We simply have a term to describe the phenomenon, allowing ourselves to talk about it more openly now.

READ: Commentary: I’ve been career oriented my whole life, until the COVID-19 pandemic took my ambition

LISTEN: Returning to the office – can you say no?

The first step to solving burnout is to recognise that you’re charred to a crisp, that you’ve reached your limit, and that your constant inability to function isn’t just “stress”.

Some signs of burnout include irritability towards things that didn’t use to irritate, avoidance of tasks you need to complete, and a lack of ability to keep up simple routines, such as checking one’s email every morning, according to senior clinical psychologist at the Institute of Mental Health (IMH) Shivasangarey Kanthasamy whom I spoke to.

Not being able to maintain simple routines has been coined “errand paralysis” in Buzzfeed reporter Anne Helen Peterson’s seminal piece on millennials as the burnout generation.

The majority of these so-called simple tasks would benefit the procrastinator, but “not in a way that would actually drastically improve (their) life”.

“They are seemingly high-effort, low-reward tasks, and they paralyse me,” she writes, citing examples like scheduling a doctor’s appointment or returning library books.

(Photo: Pixabay/cuncon)

What’s interesting is, this paralysis doesn’t make you stop doing things altogether. It just makes you stop doing the right – or productive – things.

CAN’T STOP, WON’T STOP

While burnout results in physical and psychological exhaustion, we don’t put our entire life on pause once we’re debilitated, even though we should.

READ: Commentary: Burned out while working from home? You should check your work-life boundaries

Ironically, we develop counterintuitive means to cope with the tiredness, unwittingly trapping us in never-ending fatigue.

Take doomscrolling, a term coined by Canadian journalist Karen Ho.

It is, according to NPR, to “incessantly scroll though bottomless doom-and-gloom news for hours as you sink into a pool of despair”.

Even though the behaviour stems from a need to regain some semblance of control amidst uncertainty, American clinical psychologist Dr Amelia Aldao warns doomscrolling creates a “vicious cycle of negativity” and fuels our anxiety.

READ: Commentary: Why do you not feel like working from home? You’re probably procrastinating more

The phenomenon may be more widespread than we know.

A recent comic from the New Yorker shows a man in bed, with his laptop propped atop his covers. The caption reads, “Wow, it’s only 11 – that still leaves time for me to ruin tomorrow by staying up doing nothing on the Internet.”

Then there was a semi-viral tweet by journalist Daphne Lee, who wrote about a Mandarin term she learnt that loosely translated to “revenge bedtime procrastination” – a phenomenon in which people who don’t have much control over their daytime life refuse to sleep early in order to regain some sense of freedom during late night hours.

(Photo: Unsplash/Niklas Hamann)

Might it be that the act of obsessively doing, doing, doing is so deeply ingrained in burnout that we’ve come to equate productivity to meaningful work?

Indeed, IMH psychologist Ms Kanthasamy shares with me. She recalls a case where her adolescent client’s mother felt irritated seeing her at home during the circuit breaker and not doing anything productive. In her own parenting experience, she has also felt like she wasn’t “doing enough” if she let her daughter watch Peppa Pig.

Complementing societal and cultural factors, Ms Kanthasamy says a huge internal motivating factor for chasing productivity is the thought of getting a rewarding end result, like an achievement or better self-worth, for attaining a concrete outcome.

Naturally, even in our downtime, our tendency is to do something, rather than to just be.

READ: Commentary: Sleeping more is essential to performing well at work and school

READ: Commentary: Putting in 50 hours while WFH, it’s a struggle to draw the line between work and home

WORK HARD, REST HARDER

Perhaps the most effective solution to combat the culture of overwork is to turn rest into another goal we actively pursue, another item on the to-do list, another intentionally scheduled activity.

Enter a German university offering grants to people who want to do absolutely nothing. According to British news site, The Independent, the University of Fine Arts in Hamburg is searching for people to take part in a project “examining laziness and lack of ambition”.

To win one of three €1,600 (S$2,600) Euro scholarships, applicants have to convince the panel that they will be “inactive in a particularly interesting way”.

It might seem like a tongue-in-cheek solution, but adopting its philosophy in our workplaces could be the start of solving burnout.

After all, we don’t have long-term solutions to burnout that don’t involve quitting one’s job or the rat race entirely – consequences that suggest we’ve already passed our breaking point.

Cursory solutions, such as taking a few days off work, going on a staycation or building fancy nap pods in workplaces, also generally don’t address the root cause of burnout, says Ms Kanthasamy.

But she reminds me that an individual who’s more mindful and self-aware would usually know when to take a break before even reaching burnout.

In that case, staycations or nap pods act as preventive measures, not solutions.

READ: Commentary: A necessity Singaporeans cannot afford – more sleep

READ: Commentary: I used to think a staycation was a poor alternative for being overseas. Then I took one

Making sure employees rest could include having “rest KPIs”, where the measure of success is how well you can unplug, do anything else but work, and be as unproductive as possible for the period of rest.

Better yet, adopt a system of punishment, which Singaporeans seem naturally attuned to. If someone were remotely contactable during their leave, they should get penalised rather than commended.

All this is easier said than done. Many of us still feel guilty for taking leave, even though it’s our entitlement. This mindset is what leads us to clear emails or check in with our colleagues while we’re on holiday to remain “on the ball”, often resulting in the need for another holiday to recuperate from said holiday.

But when teams are sometimes staffed to the leanest degree possible to maximise profit, perhaps organisations too should also review how they treat human capital.

(Photo: Unsplash/Siavash Ghanbari)

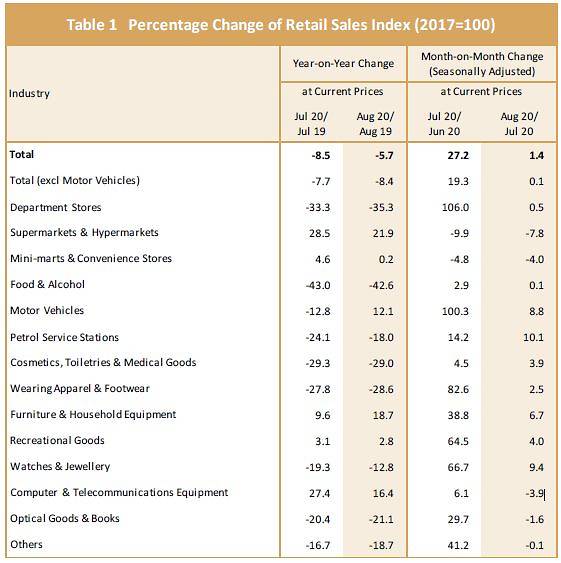

According to Microsoft’s Work Trend Index Report, 37 per cent of respondents in Singapore cite increased rates of burnout over the past six months.

“There is a need for greater flexibility and empathy, where companies can help employees create a distraction-free environment and be more flexible and empathetic in their delivery of work,” shares Rosalind Quek, the general manager of Modern Workplace at Microsoft Asia.

For instance, she says Microsoft has partnered with Headspace to bring a curated set of mindfulness and meditation experiences, which will offer workers the ability to schedule ad-hoc or recurring time for mindfulness breaks anytime.

But incorporating rest as a systemic solution ultimately involves more than change in policy or processes to shape culture. It also requires a fundamental change in mindset about how we view rest.

READ: Commentary: Coronavirus isolation a rare chance to catch up on sleep

READ: Commentary: The sandwiched generation, with kids and seniors, is staying home most days too in Phase 2

REST FOR THE SAKE OF REST

Quite evidently, the cure to burnout is an equally systemic culture of rest.

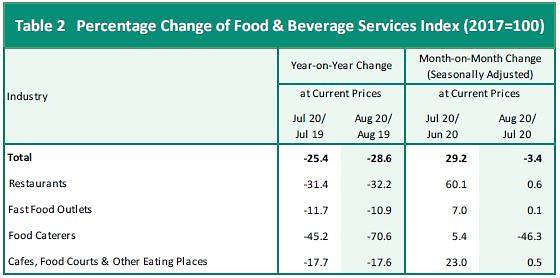

Surveys tell us the obvious: Singaporeans lack sleep. In 2018, a YouGov survey showed that only 48 per cent of Singaporeans get seven to eight hours of sleep daily.

Still, we continue to make sleep a secondary priority because staying awake to slog feels more intuitive.

To rest, we must first believe we deserve to rest – not because we’ve worked hard, nor because we want to gather energy for the road ahead, but simply because rest is necessary for a fulfilling life.

(Photo: Unsplash/Drew Coffman)

Hustle culture teaches us that we need to earn our rest. If we haven’t been working for 12 hours every day for a week, haven’t produced a remarkable piece of work, or haven’t finished that one task on our to-do list, then we don’t deserve to take a breather.

We also see rest as a means to increase our productivity, so we can churn out more work in the long run. For instance, Shopee encourages its employees to rest in its nap pods to up their productivity. And sometimes the more persuasive argument for rest is ironically whether getting more sleep might land us a promotion.

READ: How one firm is upping productivity – by helping its staff to sleep

READ: Commentary: Getting more sleep might land you that promotion

While the long term benefits are clear, rest is important for its own sake, even if we don’t do anything productive with a well-rested body and mind.

The pressure to be more productive after a period of rest ironically negates the point of letting your body and mind take a break. It only keeps the wheels whirring in the back of your mind, withholding you from a true state of rest.

Importantly, the ability to rest shouldn’t be seen as a privilege only accorded to those who can afford to hit pause on work.

“Rest is not a luxury. It’s a need, not a want. It’s a need for you to function,” reminds Ms Kanthasamy.

READ: Commentary: Millennials, the burnout generation

When society is able to embrace rest for its own sake by understanding its value on our bodies and minds, and even our relationships, rather than how it can make us productive, then perhaps we might finally make significant progress in eradicating the culture of burnout.

We can only hope the fight to rest doesn’t exhaust us any further.

Grace Yeoh is a senior journalist at CNA Insider.