SINGAPORE: As a young officer cadet in the fledgling Singapore Air Defence Command (SADC) – the predecessor of the Republic of Singapore Air Force (RSAF) – in the late 1960s, Lieutenant-Colonel (Ret) Prasad Menon was not spared the menial task of painting runway markings with a brush.

“There were not enough people,” Mr Menon, now 68, told Channel NewsAsia from his home in a quiet estate just minutes from the Kranji War Memorial. “If we had people like grass cutters, we used to say: ‘Can you help us out here?’”

The RSAF has come a long way as it gears up to celebrate its 50th birthday this year. Now it boasts more than 200 aircraft such as the F-15SG, and has over 100,000 personnel across six commands. And machines are used to paint runway markings.

As an officer cadet, Mr Menon spent a lot of time in the Seletar control tower, which the British left sparsely equipped. (Photo: Mindef)

Mr Menon, who now works as a consultant advising the RSAF on its airspace policy and operations, offered a glimpse into the organisation’s past through his years as one of its first-ever air traffic controllers.

“For night flying there were no lights, so we had to use something known as goosenecks,” he said, referring to lit kerosene tins placed along a runway. There weren’t enough people to light those too, so firemen had to chip in.

“You had to make it work, you had to make it happen,” Mr Menon added. “It was a pioneering spirit and improvisation that was there for all the elements of the air force.”

THE EARLY DAYS

Mr Menon was a pioneer of the air force. His father ran the medical centre in British-controlled Royal Air Force (RAF) Tengah, and they lived in a comfortable home on the outskirts of the base, which was located just across a nearby bridge.

British aircraft in RAF Tengah, 1963. (Photo: John Cunningham)

“Like all children growing up, it was the aircraft roar that gets you,” he recalled. “We would hear them doing circuits.” After all, getting into the base was “not a problem”. The gates were manned by auxiliary officers who lived together with him.

RAF Tengah base front. (Photo: John Cunningham)

“I don’t think they gave you passes those days, but you had to register,” Mr Menon added. While he acknowledged that there was a “clear division” when it came to what belonged to the British, locals were still allowed unfettered access.

Mr Menon would dine, play football and attend Christmas parties in the base. But there was still something else he yearned for. “The idea of flying was, of course, something that everybody around the air base hopes for, but know they will never get.”

The McGregor Club, one of the recreational facilities in RAF Tengah. (Photo: John Cunningham)

Things changed quickly. In January 1968, the British announced that they were going to pull out. They would hand over RAF Seletar first. Tengah was next.

The news hit hard, especially for families with fathers working for the RAF. Mr Menon worried for his dad’s job, but a novel “opportunity” arose: “You could say yes, people aspired to join your own air force.”

Then 18, Mr Menon had just completed the equivalent of the A-Levels, and was waiting to enter university to read law. That was until an advertisement in the newspaper caught his eye: Recruitment for air force pilots.

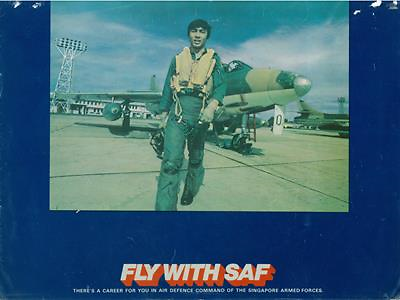

A Singapore Armed Forces (SAF) recruitment brochure for pilots in the 1970s. (Photo: Mindef)

He immediately shelved plans to study for a degree and enlisted as a cadet pilot officer in June that year. His parents offered their full support. “Whether they were really happy internally, I do not know, but they gave me all the encouragement.”

His father kept his job, and worked in Tengah till the day the British pulled out. For a short time, father and son were colleagues, but the “thrill” of joining the air force soon turned serious.

“After we joined it was quite clear that we had to provide Singapore with a credible air defence system,” he said. “That I must tell you is a very real feeling. Everybody felt the urgency and resolve to take over safely and be a force that others would respect.”

“Where it all started”: Mr Menon and 30 other officer cadets were part of the SAF Flying Platoon, set up with the formation of the SADC. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

Three months later the SADC was formed from scratch, as it hastily borrowed two Cessna aircraft from the Singapore Flying Club. The arrival of eight Alouette III helicopters, making up SADC’s first operational unit, came next.

Mr Menon said there was “anxiety” in the early days of the SADC.

“Can we continue to operate on an airfield for 24 hours if necessary? Where are my men going to come from? Do I have sufficient spares for my radars?” he said. “We knew that people were trying their level best.”

Tried they did. Everyone was consumed with putting in the training hours, he added. They realised the “enormity” of the work ahead. “People were stretched, but I don’t think anybody complained, really.”

An Alouette III helicopter landing at Seletar. (Photo: Mindef)

One of the biggest challenges then was manpower, Mr Menon said. The SADC had started with fewer than 100 personnel, and it needed people of various specialisations – pilots, engineers, air traffic controllers. “Each vocation has got to attract its own people.”

But it did attract people. They joined because of the good training opportunities. “The exposure is enormous,” he added. “They can quickly see how their contributions benefit the country.”

A DIFFERENT PATH

Mr Menon’s home is filled with air force memorabilia – commemorative plaques, a signed model of a jet fighter, a pair of headsets he used to wear as an air traffic controller.

Why did he become a controller instead of a pilot? The bespectacled man – shirt neatly pressed and tucked in – spoke softly and eloquently, recounting what would be his proudest days in the force.

Mr Menon donned this type of headset during his days as a controller. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

It began in October 1968, with a “very unfortunate” bout of pneumonia. “I was subsequently told I was being sent to air traffic control,” he said. “In those days you don’t argue with your superiors.”

Naturally, he was disappointed. “But you have to do the best you can and strangely enough you grow into your job,” he added.

For two-and-a-half months Mr Menon went through a civil air traffic controller course to learn how to manage aircraft and ensure they don’t collide. Then he jetted off to Shawbury, England to learn the military side of things.

Mr Menon at RAF Shawbury for the military air traffic controller course. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

His time in the United Kingdom was “eye-opening” because he worked with new systems and was attached to an aerodrome, where he managed live aircraft. “We were very serious with what we did,” he said.

Upon his return in October 1969, Mr Menon was commissioned as an officer. Part of the pioneer batch of six air traffic controllers, he was posted to Seletar for a two-year training stint before returning as a full-fledged controller to Tengah, “where I had grown up”.

Mr Menon’s commissioning certificate. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

Life had come full circle, but there was no time for nostalgia.

By then the SADC had bought eight Cessna 172K Skyhawks for its first flying unit, the Falcon Squadron. The hardest part of Mr Menon’s job was the “intensity”. “Everybody was training, so there was a lot of aircraft,” he said.

Compared to now, the workload for controllers then was heavier, because Singapore’s pilots were training locally “all the time”. Military aircraft from Australia, New Zealand and the UK were also flying in and out for exercises.

“Sometimes, we would have as much as about 40 to 50 aircraft at our dispersals, but not all from Singapore,” Mr Menon said, using the term to describe where airplanes are parked.

The SADC’s first Cessna was hand-painted by its airmen. (Photo: Mindef)

Working hours were stretched too. Shifts ran from 7.30am to 1pm for morning flying and resumed at 6.30pm till 11pm for night flying. “We try and get some rest, but those are things you have to do,” he added. “I think they’ve improved it now as they should.”

Nevertheless, he has fond memories of those days. In 1973, a British aircraft was forced to make an emergency night landing in poor visibility at Tengah. Mr Menon guided the plane down without a hitch.

“The pilot came up to the tower to thank us,” he said. “Very nice, very gracious of them to do that. But that’s your job; that’s what you’re there for.”

THE PROGRESS

The interview had gone on for more than an hour, but Mr Menon remained every bit as enthusiastic. He grew more animated as he talked about how the air force developed.

In September 1971 the final British aircraft flew out from Tengah, making it the last flight out of a British-controlled aerodrome. Sembawang and Changi followed soon after. Singapore flags were raised – the handover was complete.

Mr Menon was hosting officer for then-Prime Minister Lee Kuan Yew at an SADC dinner, where Mr Lee told attendees about the imminent name change. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

Four years later, the SADC was renamed the RSAF. Mr Menon started taking on more important appointments.

In 1981 he became commanding officer of the flying support squadron, calling it a milestone in his career. He also served as head of the flying support branch, before performing a similar role at air force doctrine.

Mr Menon (first row, middle) oversaw the redevelopment of Tengah in 1980, as new taxiways and runways were built. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

Mr Menon retired in 2001 as head of the airspace branch, based at the RSAF headquarters in Bukit Gombak, after 33 years in the force. Even then he was still deeply involved – he was in the midst of negotiating a bilateral issue when “they were chasing me to get this formally done”.

“So I took some time off from what I was doing, met the chief (of air force), collected the certificate and went back to work,” he mused.

Mr Menon’s retirement certificate, five Presidents later. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

It’s no wonder then that Mr Menon accepted an offer to continue as a consultant. He felt like he had more to give. But does he still have the same energy? “I would like to think so,” he said with a laugh.

The years that followed saw “tremendous growth” in the RSAF, as it shifted focus from air defence to deterrence.

“We became a full spectrum air force, which means that we are able to handle crises in peace and war,” he added. “We made use of technology that was coming in – weapons, unmanned aircraft.”

The RSAF acquired its first F-16, a multi-role fighter, in 1983. (Photo: Mindef)

The RSAF helped out in foreign crises too. Mr Menon helped to coordinate the humanitarian response to the 2004 tsunami in Aceh, where it set up a mobile air traffic control tower to replace the one that was badly damaged.

RSAF aircraft were deployed in Indonesia to help with disaster relief efforts. (Photo: Mindef)

He’s particularly proud of this effort. “They landed there in driving rain,” he said, adding that a “small group” started deploying the tower at 11pm and got it up and running by 5am the next day.

“It was very significant because people were going to an area where we knew very little about the terrain and facilities. And this spirit of improvisation that had been part of our culture for so long continued to be shown.”

LOOKING BACK

Mr Menon said the air force of his time would have needed help pulling off an operation of such scale.

“We didn’t have the infrastructure, certainly not the experience,” he said. “We do what we can, but the level of assistance and the speed at which we can move things shows how far we have come.”

The day before he retired, Mr Menon returned to his roots by controlling an aircraft at Tengah for one last time. (Photo: Ruyi Wong)

So, how different would things be for Mr Menon had he joined the air force of today?

“For one, I think I would have more answers than I had before,” he said. “I would come into an organisation that is well-established. I didn’t have that when I joined; we were learning as we went along.”

Still, Mr Menon has no regrets about his career. In June, he will celebrate 50 years in the air force, at the same time it commemorates its golden jubilee.

“Given the circumstances, I’m happy,” he said. “How many opportunities can one get to work on something one is so passionate about for such a long time, and see it grow?”