When driverless cars become the norm, they will cause a redrawing of the transport map so major it will make the changes due to Uber and GrabCar look like a few pencil marks.

A Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) study has predicted that combining self-driving cars with car-sharing means Singapore’s mobility needs can be met with just 30 per cent of the current one million vehicles.

Imagine the scale of the disruption to the billion-dollar car industry, thousands of driving jobs and miles of space now reserved for roads and carparks.

The Transport Minister himself thinks this remapping of land transport is inevitable.

Last month, when Parliament debated his ministry’s budget, Mr Khaw Boon Wan predicted that “private cars will likely start to go the way of horse carriages, if not in 15 years, definitely in 20 or 25 years’ time”.

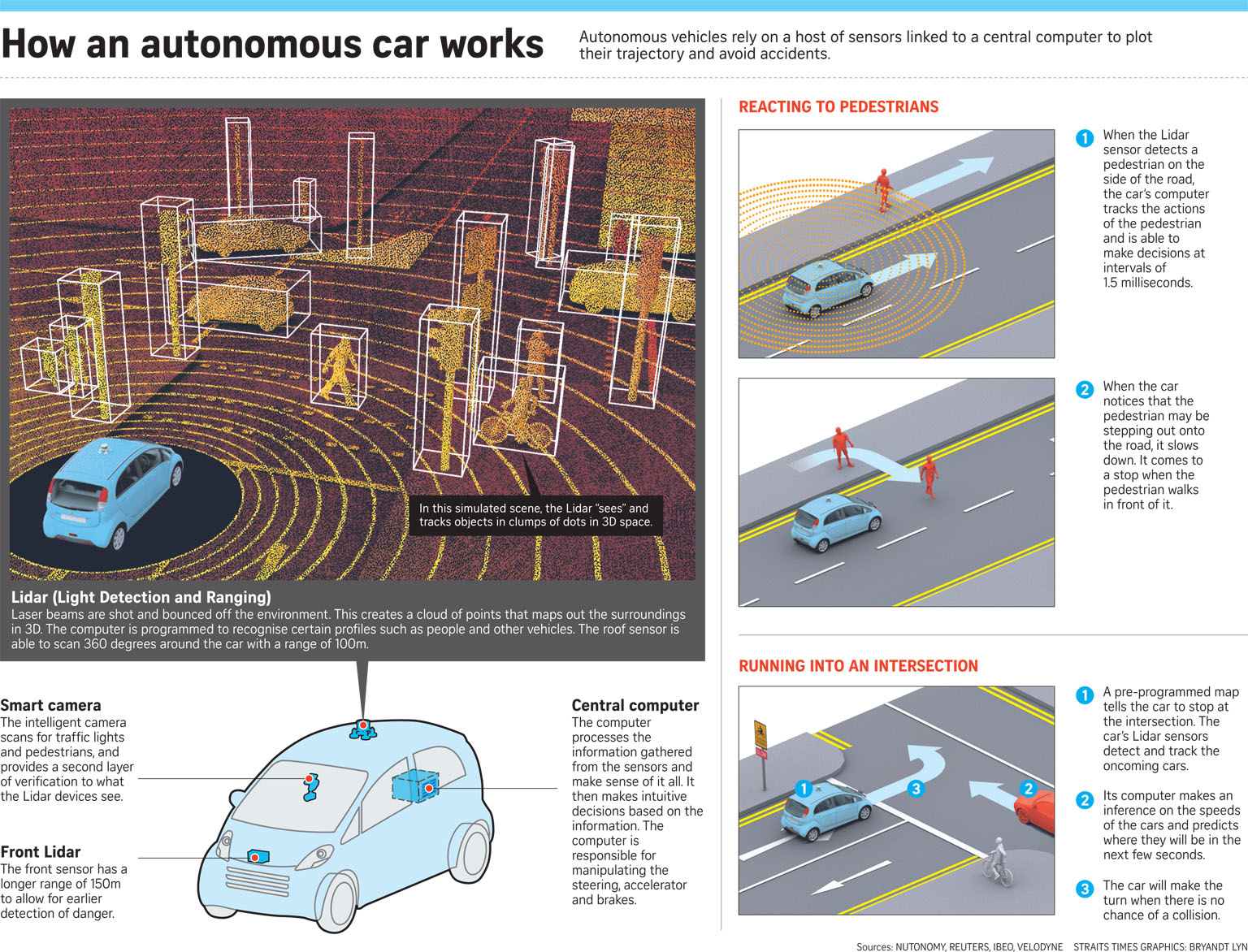

Between now and then, experts predict a steady shift towards autonomous vehicles, starting in controlled environments such as container ports, airports and education campuses. That will happen within the next five years, they reckon, because existing driverless technology – which employs sensors, cameras, laser-light scanners and mapping systems – is ready for use in such spaces.

Professor Wang Danwei, director at the Nanyang Technological University’s Centre for System Intelligence and Efficiency, says: “Drivers and other (human) users in these areas can be educated on how to behave towards these new systems.”

In fact, from the middle of this year, self-driving vehicles will be plying Gardens by the Bay. In just over two years’ time, on-demand driverless shuttles are expected to ferry visitors about on Sentosa.

Prof Wang believes that self-driving public buses can be deployed if the road infrastructure is equipped with transponders to guide the vehicles, and bus lanes are reserved primarily for their use.

For commuters, though, the big change will come when they can summon driverless pods via an app to help them travel the first and last miles to a transport node such as an MRT station, and when self-driving taxis take to the roads to ferry people from point to point.

But those disruptions could still be at least 10 to 15 years away, or even longer. That’s because more research and development are needed to enable self-driving cars to safely go onto crowded public roads with other human drivers, experts say.

THE LEAP TO PROACTIVE DRIVING

In February, a Google self-driving SUV (sport utility vehicle) collided with a bus in Mountain View, California, after the SUV’s computer wrongly assumed that the bus driver in an adjacent lane would slow down.

To be fair to autonomous cars, it must be said that that was the first accident involving a Google self-driving car after the company’s fleet had clocked more than 2.25 million km on the roads, a feat many experts consider impressive.

But for driverless cars to make the leap to being truly robust, safe, and reliable, the software algorithm used to drive them needs to shift from thinking “reactively” to thinking “proactively”, says Dr Marcelo Ang, acting director at the National University of Singapore’s Advanced Robotics Centre.

What’s the difference?

At a road intersection without traffic lights, for example, a “reactive” self-driving car will use a set of parameters to “decide” when to go, Dr Ang says. These are based on how far away oncoming traffic is and whether such traffic is in the car’s “safety zone” – a computer-defined radius around the car that tells it to stop.

“But a proactive algorithm will predict, (for example) whether the oncoming car has an aggressive driver, and will know in the next one to five seconds how the environment will change and plan the action accordingly.”

More importantly, however, such an algorithm is constantly learning from experience – akin to humans.

“After the action is made, the algorithm rates itself – how well did it perform? If it crashed, it won’t make the same prediction and action again,” says Dr Ang, who is also a co-investigator at the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology’s (Smart) Future Urban Mobility unit.

If the process of “deep learning” – mimicking a human brain’s ability to recognise patterns through huge data sets and make predictions – can be programmed in self-driving cars, it would propel them to the next level.

But that could take around a decade more, Dr Ang reckons.

SEEING THROUGH THE RAIN

Driverless cars also have to overcome some very real physical shortcomings that currently limit their usefulness.

This may come as a surprise but researchers have yet to work out how to get such cars to work reliably in bad weather. Heavy rain, for example, is not something such cars can deal with. That needs to be fixed if driverless cars are to become a true point-to-point, on-demand mobility solution which can be relied on at any time of the day, says Prof Wang.

Explaining why these smart cars struggle with a weather phenomenon that humans take in their stride, Prof Wang says: “When it rains, human (drivers) can (visually) ‘lock in’ the yellow road markings, and consider the rain drops as disturbances.

However, the laser scanners and cameras on the driverless cars are affected by the poor visibility.”

To tackle this, Prof Wang together with researchers at the ST Engineering-NTU Corporate Laboratory are experimenting with signal-processing techniques so the car’s computer can “remove” the rain, in the same way that a human does.

An alternative solution is to change the frequency at which the car’s cameras capture the road images to account for the intervals between raindrops. “When the frequency is right, we can see through the rain,” Prof Wang says.

READY, GET SET, GO!

While the road to a driverless future is still fraught with challenges, governments, carmakers and tech companies around the world are already paving the way for its eventual acceptance.

In anticipation of these vehicles hitting the streets, lawmakers in American states such as Nevada and California have enacted regulations to allow autonomous cars on the road.

In Singapore, the Government formed the Committee on Autonomous Road Transport in Singapore (Carts) two years ago.

Last October, Carts identified four main tracks along which the Government will encourage the use of self-driving vehicles: mass transport on fixed and scheduled services for travel within and between towns; shared services for point-to-point and first- and last-mile travel; freight; and utility operations, such as road sweepers.

Other countries are more ambitious: China has plans for a draft road map to put autonomous cars on streets and highways within three to five years.

The British government has said it will allow driverless car trials on highways by the end of next year, and has committed £150 million (S$296 million) to harness new technologies, including a “Wi-Fi road” that could see cars and infrastructure wirelessly connected.

The key to making driverless cars a reality in Singapore will be private sector-led trials.

Singapore has given the green light for three groups to carry out such trials along a 6km test route in research-cum-business park one-north – a real-world environment with heavy and light traffic situations, and motorists and pedestrians on the roads.

The three organisations with approval to test-bed their vehicles there are the Institute for Infocomm Research under the Agency for Science, Technology and Research; the Singapore-MIT Alliance’s Smart; and start-up nuTonomy, an MIT spin-off.

Associate Professor Park Byung Joon of SIM University says that, given Singapore’s dense road network and heavy vehicular traffic, care must be taken to mix self-driving cars with human-operated ones as the technology is, in his view, not mature yet in this respect.

“In the future, when every car is autonomous and driven by a computer, it’s not a problem. But now, there will be some issues – how computers and human drivers mingle. Driverless cars drive by the book and law, but humans don’t,” he says.

But when the technology matures, Prof Park says, Singapore can be an ideal test-bed for research firms precisely because of its traffic density, and the Government should open more road spaces to attract such companies here.

“Even the quietest heartland area in Singapore is going to be a far more complex environment than what Google is testing in, in the US,” Prof Park says.

CONSTRAINTS AS FUEL

Singapore’s constraints, including its land and manpower shortage, may well fuel its drive to automate driving sooner rather than later.

The city state has close to a million motor vehicles on the roads, and the 12 per cent of land space set aside for roads is close to being fully utilised.

“Building more train lines,” says Dr James Fu, nuTonomy’s director of Singapore operations, “will eventually lead to a marginal increase in transport efficiency.”

That’s because “people will say they don’t live near a station, and they want more stations. But more stops will just lead to longer end-to-end travelling time for everyone,” he adds.

Dr Fu is hopeful that as the authorities open up more road estate – such as that in one-north – the technology powering today’s driverless cars will evolve in sophistication.

“Driving in an urban environment with other human drivers – that’s the biggest challenge. But people are confident of solving this,” he says.

“People’s driving behaviours are different in Orchard Road, the CBD and Jurong East, for example. So the more access you have to different kinds of public roads, you can see the limitations of the current algorithms, what situations they can and can’t handle. Right now, we don’t know what we don’t know, ” he adds.

Besides roads, driverless cars have the potential to alter city infrastructure by reducing the need for carparks. In a sharing economy, autonomous vehicles will not need to be parked as they can drop off their passengers and proceed to the next destination.

Road space can also be yielded to pedestrians and cyclists as autonomous cars will have the ability to travel closer to one another, and at road speeds which are constant, and less erratic than their human counterparts.

Perhaps the greatest gain and the one most espoused by its proponents is safety. Studies have shown that around 90 per cent of road accidents are due to human error, and driverless cars – whose computers are never tired or distracted – are touted to be safer.

“The driverless car,” says Dr Ang, “is not affected by emotions. When you overtake it, it doesn’t get angry. It’s not affected by tiredness, is more objective and has the potential of exceeding a (human) driver’s capabilities.”

This article was first published on May 14, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.