SINGAPORE: The year was 1972 and 12-year-old Jeremy Monteiro was in the living room of his family home. He was crying.

His concerned mother asked why.

“I said, ‘Mum, I have never heard anything so beautiful in my life.’ I decided then that I wanted to be a professional musician and more skilled towards jazz,” he tells me during our interview.

When I ask him what he was listening to, he pauses. For a moment, I feel he might start crying right there in front of me. But he doesn’t.

Instead he tells me with a faraway look on his face – as if he were again listening to the jazz record that made him decide the course of the rest of his life – Brown Ballad composed by Ray Brown, performed by Quincy Jones, featuring Toots Thielemans on the harmonica.

“Just the way Toots was playing the harmonica. The whole thing was so beautiful, the melodic lines were so impeccable.”

About 30 years later, he would share the stage with Thielemans at the Victoria Concert Hall as part of the Singapore Arts Festival.

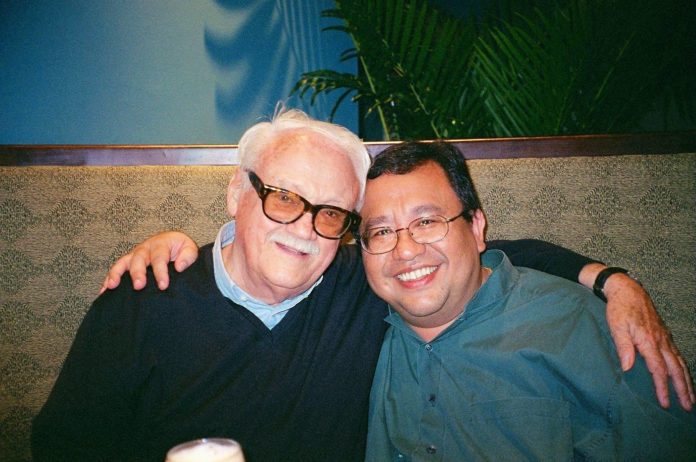

Jeremy Monteiro with his idol, Belgian-American jazz musician, Toots Thielemans. They met and performed together in 2002. (Photo: Jeremy Monteiro)

Dubbed Singapore’s King of Swing, Mr Monteiro, a jazz pianist, singer and composer, has won multiple awards including the Cultural Medallion in 2002 and performed with jazz greats such as James Moody, Ernie Watts and Lee Ritenour. He is also known for composing National Day songs such as One People, One Nation, One Singapore.

Today, he performs at festivals and jazz clubs all over the world and produces albums for himself and others. In fact, he will be producing Laura Fygi’s next album.

SERENDIPITY

Mr Monteiro shot to international fame with his 1988 performance at the prestigious Montreux Jazz Festival in Switzerland.

“Although I played for only one night, the coverage in Singapore across many media lasted almost eight months. This allowed me to suddenly come to the forefront of the collective consciousness.”

He was the first Southeast Asian musician to perform with an American band on the main stage of an international jazz festival.

“It was serendipity. It just so happened that the Montreux festival director was having a meal at a cafe where they were playing an album of mine. He heard it and said, ‘We must get this guy’.”

At that point he was a nobody. He was part of a band, Monteiro, Young and Holt. Young and Holt were the original drummer and bass player in the Grammy award-winning Ramsey Lewis Trio from the US.

“They started to come to Singapore in the 80s. When they came over, I started playing with them and I asked them to form a project band with me.”

Monteiro, Young and Holt received a three-minute standing ovation at Montreux.

Redd Holt, Jeremy Monteiro & Eldee Young. Redd Holt is still actively at 83 years old in Chicago. (Photo: Jeremy Monteiro)

He hadn’t imagined any of this when at 16 he decided he was done with school.

“I was a decent student until I hit secondary 3. At that point, I started to become very interested in music.”

He had been taking music lessons since he was seven years old and music was an intrinsic part of family life.

His father, a policeman, moonlighted as a jazz guitar player. He would have jam sessions at home and bought jazz records that would fill the house with melodies practically all day.

“I was trained in classical piano, but I loved jazz more because I could extemporise, improvise. It was a wonderful mode of expression for me.

“I can’t really explain it. Playing music centres me. It allows me to to feel a congruency between my mind, body and soul. Instrumental music especially is the language of the heart. It allows me to communicate without saying a word.”

HIS DAD “SABOTAGED” HIM

While his dad was a musician, his son’s ambitions to go into music full-time made him nervous because “it wasn’t an easy life.”

“He started to sabotage me in the best possible way, wanting me to concentrate on my studies. He said he’d send me to the best university if I did well for my O-level and A-level exams. I deliberately didn’t do well at O-levels because I didn’t want to go any further.”

When asked if he felt any fear taking what’s deemed to be a risky path in a Singapore that emphasises academic excellence, he says, “No, I didn’t feel any fear. Maybe it was just youth.”

His fearlessness paid off. He committed himself fully and did just fine, starting as a musician at Chinese nightclubs to pay the bills.

His mother was pivotal in his entry into jazz clubs in Singapore.

She was a private nurse to an old man who had just had heart surgery at the time.

“He owned a club and when she told him I was a jazz pianist, he gave me a job.”

For many years, Mr Monteiro was a session pianist and performed on more than 300 pop records.

GENERATIONS OF JOBLESS MUSICIANS

While Mr Monteiro still makes “decent money” doing jazz gigs, both overseas and in Singapore at corporate events and clubs, he bemoans the dearth of jazz clubs in Singapore.

Many have closed over the years.

“The Government has done amazing things with education. Having things like School of the Arts, and La-Salle and the Nanyang Academy of Fine Arts. My worry is that a lot of musicians who graduate from these institutions end up having no gigs. They just have nowhere to play. They’re jobless.

“I’m already established so I can get jobs overseas and at functions in Singapore. But all these musicians will be coming out with their degrees or diplomas in music and what they end up doing is going back to teach the next generation of jobless musicians.”

Perhaps there is no demand for jazz musicians, which would explain the club closures.

“Well, people started getting more distracted. There are so many things you can do at home now to entertain yourself.”

But he believes that if live entertainment were to be made available in heartland neighbourhoods, there would be a healthy demand.

“Nowadays, we have new towns that have everything. So of course, people don’t want to leave their neighbourhoods.”

LOOSEN PUBLIC ENTERTAINMENT LICENSE RULES

“If we made live entertainment available at neighbourhood cafes and restaurants, I’m sure people would go. Our public entertainment license restrictions need to be loosened.”

There are obstacles.

“Within neighbourhoods, they worry about noise. There was one case of noise complaints from a particular establishment. They had some problems with licensing after that. But when I went to investigate, you couldn’t hear the music from outside the club. It was because at midnight, for some reason, everybody spilled over to the front of the club, and started making a whole lot of noise. The complaints were because of these people.

“So you should control the crowd that’s making noise. Maybe don’t serve alcohol at these establishments. But don’t control the bands, and the licenses.”

He’s deeply frustrated by this issue which he deems a “failing of our scene.”

“Our public entertainment rules and regulations are actually meant really for a time when there were gangsters in Singapore and girly bars and so on. Today, we have a different scene where there are also things like folk music places or jazz places that we can have. Provisions need to be made for these all over Singapore.”

Jeremy Monteiro performs all over the world, from Bangkok to New York. (Photo: Norhendra Ruslan)

This is especially important because making money out of CD sales is not lucrative anymore, he points out.

He rails against piracy and even music services like Spotify.

“It’s the lesser of two evils, but it’s still institutionalised piracy because the songs are going for a very low fee.”

But some have argued that piracy may not be such a bad thing. It at least increases exposure and that exposure generates more in terms of concert ticket or merchandise sales.

“Generally, people need to understand that to take someone’s music for free is the equivalent of walking into someone’s house and walking out with their things. We feel violated as artistes, musicians or filmmakers when people steal our work like that.”

What’s the solution then?

“The Government is doing things like blocking sites. It’s a bit of a cat-and-mouse game but I think they’re very much on it. They should be even more stringent because entertainment could actually be a huge part of the economy.”

To do his part to support the local jazz scene, he has started the Jazz Association of Singapore.

He’s rallying to bring jazz to the neighbourhoods and launching a scholarship programme for young artistes.

They also have an orchestra mentored by Grammy award-winning musicians and mentors.

THE LAST EMPEROR OF JINGLES

Mr Monteiro’s talent goes beyond jazz.

“In the past, at any one time, there would always be someone who had about 70% of the jingles market. In the early 80s, it was me. It helped me pay for my ‘jazz habit’. I had the means to, if there were a jazz festival somewhere in French Riviera, jump into the plane and go and listen.”

But even though he never saw jingle production as a passion, he put his all into it.

“My mindset was: I will produce the most amazing piece of music ever written in the history of mankind. That’s how I approach everything. Of course, after I walked out of the studio, I would just forget about what I did because that wasn’t really my artistic expression. But thankfully, even throughout my jingle career and my pop session work, I would go to my jazz gigs at night. These made me decent money too.”

His reign in the jingles production market came to an end after 10 years.

“Computer music started coming around and people could actually set up little bedroom studios. Many came from overseas too. That was the end of being able to have dominance.”

Hence he became known as “The Last Emperor of Jingles”.

He stopped altogether in the early 90s to focus fully on his jazz career and continued releasing albums.

In fact, one of his first few, Faces and Places, outsold saxophonist, Kenny G’s album in 1987.

FEELING FEAR

While he didn’t feel any fear as a teenager starting an unconventional career, Mr Monteiro did feel fear as an adult.

Between 1981 and 1991, he opened and closed seven recording studios.

“When I started getting really successful in jingles, I realised I didn’t like paying tens of thousands of dollars to recording studios every month. So I wanted to have my own. I would always find means to open the next one, maybe bigger and with better facilities. But the seventh one was bad. It was more than half a million dollars of investments and then, all of a sudden, my business went away because of the new production houses from overseas that opened here.“

He had about S$800,000 worth of debt and spent 10 years paying it off.

“I feared not being able to provide for my family, but we managed being very, very frugal.”

Today, he owns Showtime Productions, which is a business vehicle for his activities.

It books musicians for corporate functions and conventions and represent artistes.

While the business failures were painful, Monteiro says his childhood experience made it easier for him to accept a frugal lifestyle.

His father opened up a successful business after he retired from the police force.

“He got quite wealthy to a point where I remember we used to have two drivers in the family. One for him and my mum and one for me and my sister, Sheila. We’d go school in a chauffeur-driven car. But then the business took a turn for the worse and all that went away.”

“It was a culture shock. We moved from a big house to a small apartment. From travelling in a chauffeur-driven car to taking bus number 209 from our flat in Taman Jurong to school.”

It wasn’t tough for long though.

“I got over it. I remembered what my uncle said. As long as you have enough to eat, a comfortable bed to sleep in and a piano to practise on, it’s enough.”

“I’ve been made to feel humble many, many times and nowadays I never just judge a book by its cover. Some unassuming fella could jump at the piano and just kick your butt!” says Jeremy Monteiro. (Photo: Jeremy Monteiro)

NO GRAMMY OR OSCAR

The young Monteiro had bold ambitions. He wanted to win a Grammy and an Oscar for scoring a Hollywood film.

But none of this happened.

“I’ve only reached the entry stage of the Grammy Awards which is just below nomination.

“The one time I had a chance to do a score for a Hollywood B-movie, the project didn’t go ahead.”

Indeed, a lot has been said about Monteiro having performed with the greats of the scene, but why hasn’t he managed to become one of them in terms of recognition?

Was he just not good enough?

“At one point there were some people who wanted to try to help me be nominated for a Grammy. When I listened to what the process was all about, how political it was and how much money you needed just to get nominated – you have to have at least S$35,000 dollars to spend on PR agents and to even be heard – I thought to myself, do I really want to spend that kind of money?”

But why not? Isn’t that kind of recognition worth it?

“At that time, I didn’t have the money to even think about doing stuff like that and now, I wouldn’t want to waste my money on that anymore.”

“I don’t really care about being famous anymore. I’m happy with being recognised in this region. Most people start off with just loving the music and then they move on later on become more commercial. I’ve actually gone the other way.”

I ask if he fears that his not caring about being famous would be seen as as excuse for simply not being good enough.

“But the thing that drives me to write, play and practice is totally different now. It’s no longer those things. Now my impetus is just really to produce the best possible music that I can produce. I’m lucky enough now where there’s a flow, there’s enough of an income that I don’t really worry so much about awards. I just completely feel in love with music again. ”

OUR COLONIAL HANG-UP

However, the lack of recognition of local musicians on home soil bothers him.

He attributes it to Singaporeans’ “colonial hang-up”.

“Some bands in the past had a good run. But even then, sales were not fantastic, not like those for American artistes.”

This unfortunately extends to all other products as well.

Two years ago, he launched J Monteiro watches in celebration of his 40th anniversary in music.

“I went in with a very prominent Singaporean watch maker who has got an international brand that’s now global. When we started off, we were struggling but the moment we decided to move our manufacturing from Hong Kong and Singapore to Germany, our sales went up because of the ‘Made in Germany’ mark.”

“You might be able to find quick fame, but if you’re not ready to put in the work for the long-term, you won’t get anywhere,” says Jeremy Monteiro. (Photo: Jeremy Monteiro)

GOVERNMENT NEEDS TO REACH OUT TO ARTISTS

There are many other positives in Singapore though. He praises the Government’s efforts to support the arts.

“Things like the Arts Creation Grant are unheard of in some countries.”

However, he says the grants application process, while less onerous than before, is still an issue.

“It’s still quite onerous. So sometimes the people who get the grants are not those who necessarily deserve it, but those who are really clever at filling up forms.”

Mr Monteiro feels the authorities could also afford to boost outreach efforts.

“An old artist with a lot of talent who spends a lot of time in his studio may not be aware of your grants. So have an arts officer go and help these artists.”

However, hardship is par for the course, he says.

“In New York, the best actors on Broadway and off Broadway are waiting tables two-thirds of the time to pay their bills. It’s part of journey. When you get better, you’ll make more.”

“Complaining doesn’t do any good. You’ve really got to just get on with it.”

LEARNING LESSONS AND MAKING AN IMPACT

“With social media these days, a lot of people survive on the dopamine rush of ‘likes’. You might be able to find quick fame, but if you’re not ready to put in the work for the long-term, you won’t get anywhere. It’s a lesson many artistes learn.”

He himself has learnt many over the years including humility.

“I’ve learnt to remember that we are masters of our own level. Nothing more, nothing less. There will always be people who are much better than you are.

“I’ve been made to feel humble many, many times and nowadays I never just judge a book by its cover. Some unassuming fella could jump at the piano and just kick your butt!”

While he’s proud of his musical career, he does have some regrets.

One of them is having lost money in his production businesses.

“I would actually be quite rich now if not for the fact that at some point I lost everything, lost all my money, almost lost my home. I think to myself, why did this happen? Why did I have to suffer this?”

He quickly turns this around though.

“Maybe the universe designed this to happen because I’m actually, by nature, quite a lazy person. If I were rich, if I had won the lottery or if I had never lost any money, I’d be sitting on a pile of cash now, but I would not have done all the things that I’ve done and I would not have worked so hard to create music, to reach out to audiences.”

When asked about the proudest moment of his career so far, Mr Monteiro struggles.

“Having done this for over 40 years, I really can’t remember everything. Sometimes the best performances happen in an empty jazz club late at night when there are only six people listening to you. Someone in the audience of six could be tearing because they loved the way you played a ballad.”

No doubt, Jeremy Monteiro wants to continue having this impact on others, similar to the impact his idol, Toots Thielemans had on him more than 40 years ago.