Singaporean workers had much to cheer about last year.

Citizen unemployment was low and the labour market remained tight with more jobs chasing available workers, even though redundancies grew as well.

The nominal median wages of Singaporean workers grew 6.5 per cent last year.

After adjusting for the negative inflation of 0.5 per cent, the real growth of wages was 7 per cent.

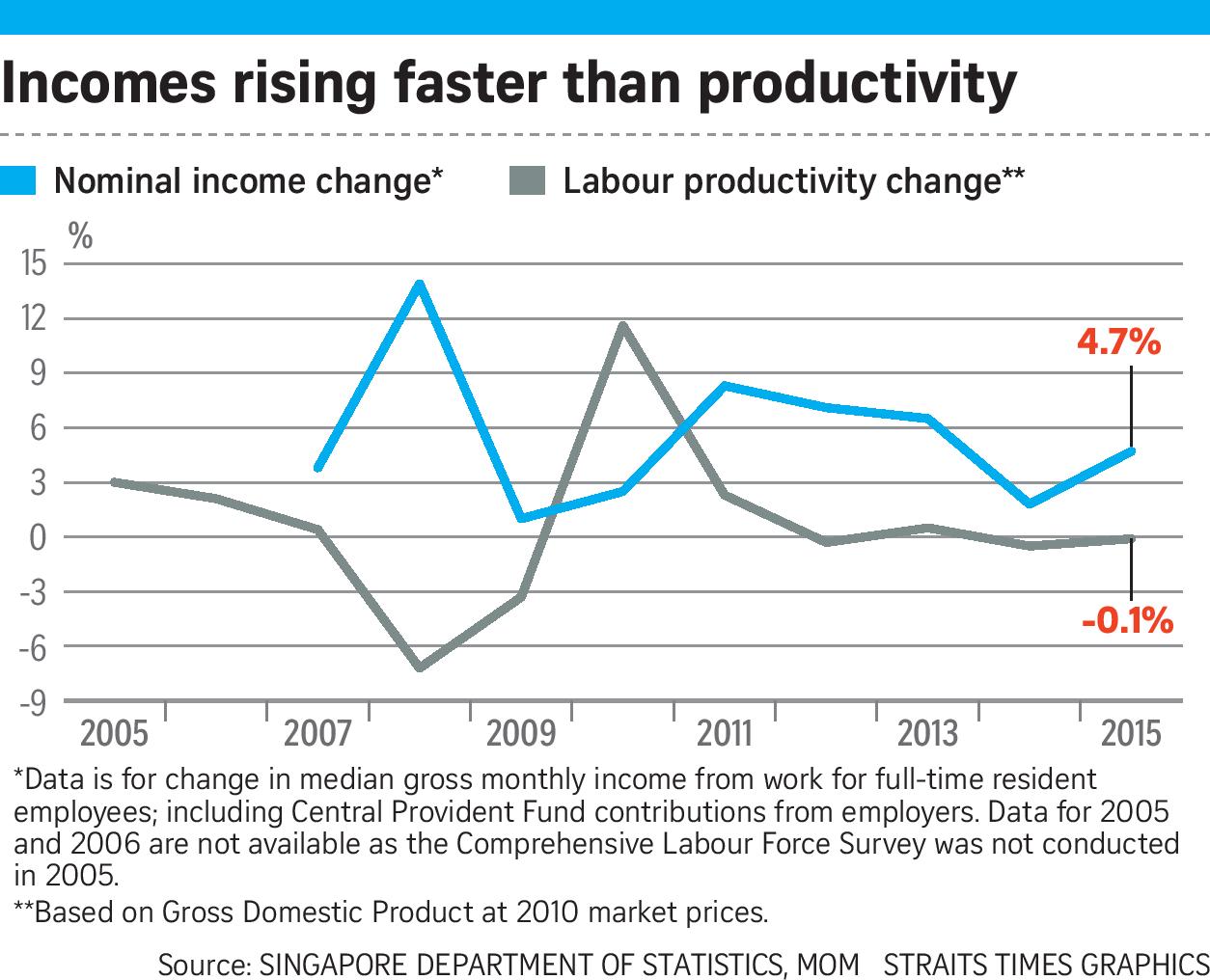

But even as wages raced ahead, productivity growth remained tepid. It shrank by 0.1 per cent last year.

This has led some analysts to question if these wage increases are sustainable over the longer term.

Can too much wage growth be a bad thing in the long run?

PRODUCTIVITY VS WAGES: A SIMPLE EQUATION

The problem of wage growth outstripping productivity growth in Singapore is not a new one.

In fact, a chart drawn up by The Sunday Times on productivity and wage changes in the last decade found that wages grew faster than productivity in eight of the past nine years.

The only year when wages lagged behind productivity growth was in 2010 when productivity grew 11.6 per cent and median gross income grew 2.5 per cent as Singapore rebounded from the global financial crisis. (See chart.)

When asked if it is worried about wages rising faster than productivity, the Manpower Ministry (MOM) would only say: “Wage growth may fluctuate from year to year, and it is useful to look at a longer period.”

It did not shed more light on the reasons behind the 7 per cent wage hike of Singaporeans or the long-term trend of wage growth.

But wage growth without a corresponding rise in productivity is a recipe for disaster, said economists.

In the recent debate in Parliament on MOM’s annual budget, Manpower Minister Lim Swee Say put out some simple maths to illustrate the dire situation of low productivity.

Economic growth is a combination of both manpower growth and productivity growth.

The problem with Singapore, however, is that recent growth has largely been powered by manpower growth.

Over the past five years, the Singapore economy’s growth of about 4 per cent a year was powered solely by manpower growth, while productivity was more or less stagnant, Mr Lim told Parliament.

Add in a shrinking local labour force and a slowing foreign workforce growth, and the result is simple: Growth will fall.

“Without a breakthrough in productivity growth… low growth will become the new norm,” he warned.

And if productivity does not improve, the country’s economic competitiveness over the long run will take a hit, economists pointed out.

Said Singapore Management University (SMU) Professor of Economics Hoon Hian Teck: “Wage growth that outstrips labour productivity growth translates into declining profit margins, business closures, and layoff of workers.

“Unless accompanied by a depreciation of the Singapore dollar, the increase in unit labour costs also implies a loss of international competitiveness.”

Singapore Business Federation (SBF) chief executive Ho Meng Kit agreed.

“If wage growth continues to outpace productivity growth, we will price ourselves out of a globally competitive market. Our businesses will be uncompetitive,” he said.

In a paper published in February, Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) economist Foo Xian Yun found that from 2005 to last year, labour productivity grew annually by 0.5 per cent.

But the real wages of the resident labour force grew by 1 per cent annually.

If employers’ Central Provident Fund contributions were added, the annual wage growth was even higher at 2 per cent.

“It will be difficult to sustain increases in wages over the longer term without a corresponding increase in productivity, given the potential impact on our economy’s competitiveness,” she warned.

SEARCHING FOR SOLUTIONS

But while it is easy to understand the maths behind the productivity challenge, fixing it is a lot harder.

For one thing, it is a difficult task just trying to get an accurate measure of productivity.

Economists point out that the way labour productivity is measured – gross domestic product divided by the total number of workers – is too crude.

This is because of the large pool of lower-skilled, low-wage foreign workers present in the Singapore economy, said labour economist Hui Weng Tat from the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy.

Many of these low-skilled workers end up doing low-value jobs and are also not eligible for subsidies to upgrade their skills.

As a result, overall productivity is pulled down, especially if companies continue to rely on large numbers of foreign workers.

“Productivity performance is the outcome of joint team effort of both local and foreign workers,” said Associate Professor Hui.

The other fear is that should wages continue to push above market rates for an extended period of time, when a recession hits, workers could take a hard hit, with large numbers of layoffs.

On the flip side, the rapid wage growth could also be the result of distortionary factors in the economy.

Government policies in recent years also probably accelerated the pace of wage growth among Singaporeans, said economists.

Prof Hui said government wage subsidies like Workfare Income Supplement (WIS) and the Wage Credit Schemes could have raised wages without corresponding productivity improvements.

The WIS scheme was introduced in 2007 to boost the income of low-wage workers.

The Wage Credit Scheme was introduced in 2013 as a three-year scheme under which the Government co-funds 40 per cent of the wage increases that are given to Singaporean employees over 2013 to last year. It has been extended to next year at a lower co-funding level of 20 per cent.

Said Prof Hui: “Both schemes increased income without providing incentives for the employer to raise productivity through training or job and process redesign.”

Correspondingly, the national push to raise productivity, which includes programmes like the Productivity and Innovation Credit scheme launched in 2010, has not made a tangible impact on the productivity numbers.

NOT ALL GLOOMY, YET

But while economists and businesses are clearly worried about Singapore losing its competitiveness should wages continue to push ahead of productivity, some said that it is not all doom and gloom yet.

For many companies, including multinational firms, the decision to set up shop in Singapore rests on a multitude of factors.

Labour is a big part of that equation but firms also have other reasons for wanting to do so.

So far, Singapore has managed to retain its top billing in many international surveys of economic competitiveness.

For instance, it ranked second in the World Economic Forum’s Global Economic Competitiveness Report last year.

NUS economist Tilak Abeysinghe noted that commercial rents became lower in the second half of last year.

“There may not be a substantial erosion of international competitiveness as yet,” he said.

SMU’s Prof Hoon said that there are other factors that continue to make Singapore attractive to foreign investors.

“Our strong legal and corporate infrastructure, our strong economic link with the global economy, and a forward-looking and eager-to-learn workforce all provide us a margin of advantage,” he said.

It comes down to whether Singapore workers are able to make themselves invaluable to employers, said SBF’s Mr Ho.

“So long as our workers provide a premium to the companies they work for exceeding their cost, they will be competitive.

“However, that premium is no longer a given. It has to be worked for and earned,” he warned.

The productivity push has also made progress since it was launched, with the Government taking a more targeted approach in tackling it now.

Earlier this month, Deputy Prime Minister Tharman Shanmugaratnam identified the laggard in the productivity race: the domestic sectors of the economy.

From 2011 to last year, the average annual productivity growth in outward-oriented sectors, such as manufacturing and finance, was 3.2 per cent. But in the domestic sectors such as construction and retail, it was 0.2 per cent.

Mr Victor Mills, chief executive of the Singapore International Chamber of Commerce, is not surprised by how the domestic and export sectors responded to the productivity push.

“The export sectors have no choice (but to innovate) because they’re competing globally,” he said.

Lastly, Singapore’s challenge is not a unique one as others are also grappling with the same problem. This gives the country some buffer to find the right solutions.

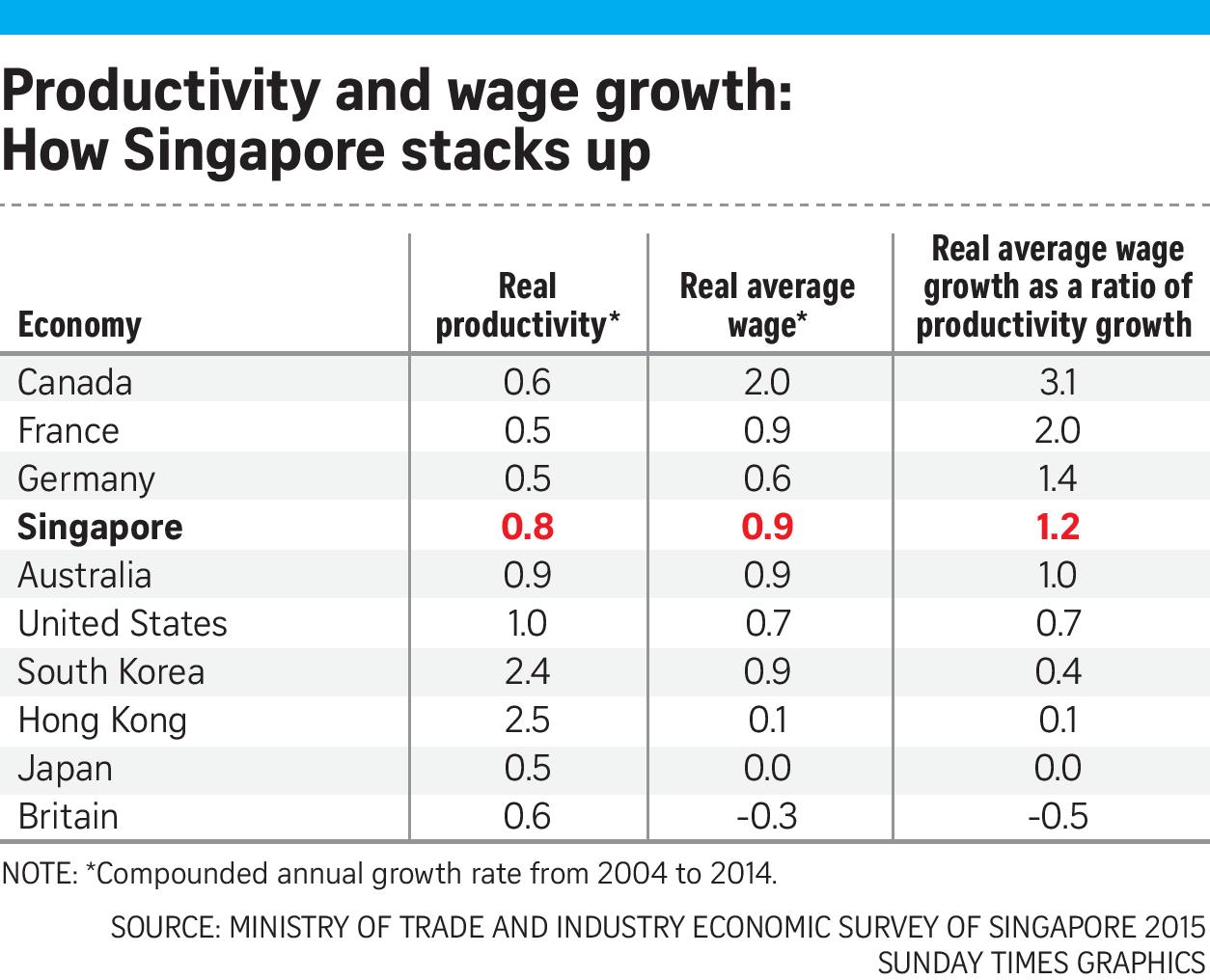

According to the MTI paper last year, the wage and productivity growth trends of nine developed economies from 2004 to 2014 showed that in countries like Canada, France and Germany, productivity also lagged behind real wage growth.

But in countries like the US, South Korea and Japan, real wage growth was lower than the productivity gains over the same period.

Said Ms Foo: “Apart from helping export-oriented sectors to restructure into higher value-added products and services, emphasis should also be placed on raising the productivity of domestically oriented sectors in order to sustain wage growth in these sectors.”

The $4.5 billion Industry Transformation Package introduced in the recent Budget is proof that the Government has not given up the fight to raise productivity.

Workers and employers now need to roll up their sleeves and get down to the hard work of getting more value from the same amount of resources.

Singapore’s economic competitiveness and its workers’ wages depend on it.

This article was first published on April 24, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.