SINGAPORE: It is not often that a book by an academic makes the bestseller lists.

But for the past four months, sociologist, Teo You Yenn’s This Is What Inequality Looks Like has flown off the shelves of local bookstores, and was even brought up in Parliament by Nominated Member of Parliament Kuik Shiao-Yin in her speech about income inequality in Singapore.

In recent weeks, as Parliament convened to debate the President’s Address, the income gap took centre stage again, with Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong and others raising the issue of inequality.

Mr Lee emphasised the need for society to maintain an “informal and egalitarian tone”.

Education Minister Ong Ye Kung argued for developing more pathways and opportunities in education and training, and changing mindsets about academic qualifications.

This would, to some extent, increase social mobility.

But Dr Teo feels that changes need to be bolder. During our interview, she mentions re-examining what is rewarded and what is punished in the education system and whether standardised tests like the PSLE do more harm than good.

To listen to the full interview, click here.

Her work, however, goes beyond education to examine the impact of the challenges families face and, as we talk, it becomes clearer that she feels universal welfare is something worth seriously considering even though Singapore’s policies are largely geared towards self-reliance.

In fact, Mr Ong said that while the Government must and will continue to extend assistance to the disadvantaged, self-reliance is a more dignified option over “easy and unconditional” handouts.

DISCOMFORT, ANGER, SADNESS AND ADMIRATION

To understand Dr Teo’s call for bolder measures, perhaps one must get acquainted with her work which began with a “simple goal”, she says.

It was to better understand the everyday experiences of those living with low incomes.

In her book, she says she visited two HDB rental flat neighbourhoods over the course of three years. Each household had an income of S$1,500 or less.

The Associate Professor and Head of Sociology at Nanyang Technological University admits that her own high-income lifestyle was very different. Merely the act of travelling back and forth between her home and those of the people she spoke to was a powerful experience.

“The stark contrast made me extremely uncomfortable. I also felt a great deal of anger at the injustice of the disparity. I felt at various time a great deal of sadness. I felt empathy, but I also felt admiration.”

She notes in her book that regardless of their circumstances, those she spoke to cared deeply for the well-being of their children and it was common for them to, for example, skip meals so that their children could eat.

“They are giving up real things. I think that is to be admired and acknowledged.”

It was to make this group of people seen that she wrote the book in a manner quite contrary to traditional academic writing.

She inserts herself and her perspectives on the findings because she says it was “key to shifting our lenses for viewing inequality and poverty more fully”.

She also visited six other neighbourhoods a few times to get a sense of how different neighbourhoods might be.

She made 90 visits in total, spending three to four hours each time and speaking to two or three families during each visit.

An HDB rental block. (Photo: Teo You Yenn)

In all, she spoke to more than 200 people, growing comfortable in their homes while listening to their stories.

As I wrote this, I realised that listing these statistics risks reducing the people she met to impersonal, disembodied numbers.

Dr Teo herself was careful not to do this. Hers was an immersive experience. She would sit on their living-room floor and listen to how day-to-day challenges were holding them and their children back.

But she tells these stories in the book largely as a matter of fact and without embellishments.

She tells of the mother who is afraid to walk through the nearby shopping mall with her kids because she’s afraid they’ll ask her to “buy this, buy that” when she can’t possibly afford to.

She tells of the family who had to share a 2-bedroom interim rental flat with another family. The bathroom floor was “so disgusting” that the children wouldn’t enter it without slippers on. They were eventually evicted when they couldn’t pay the rent and ended up living in a rented van.

She tells of how their children are impacted as a result of such conditions and how they have problems thriving in our education system as a result.

ALL OF US HAVE A STAKE

It doesn’t take any embellishments for their stories to make one consider how, while Singapore has prospered as a nation and many of us have progressed, there are others who seem to be standing still.

Dr Teo says while she hopes policymakers read the book, she did not write the book for them.

“I wrote the book for all Singaporeans. Many Singaporeans care about the problems of poverty and inequality, have aspirations toward greater equality, and are interested in knowing more about how to think about these issues. All of us have a stake in thinking about and discussing what we want to see in our society.”

She says her work urges us to not see the poor in Singapore as merely people who have “fallen through the cracks”.

Instead, she encourages a careful consideration of how policies that have benefited others could be systemically working against this group.

“I TRY NOT TO HELP MY DAUGHTER WITH HER HOMEWORK”

Before we discuss policies, she emphasises that the choices each of us make can also have an impact.

For instance, by demanding ever higher standards for our children in school are we encouraging practices that marginalise this group further?

In her own life, she has already made some adjustments.

“I try not to help my daughter with her homework. No tuition, no enrichment classes. My husband and I try not to intervene too much, so that she doesn’t have more advantages than she already has. She’s average. I think she has plenty. She’s grown up surrounded by books. She has been read to for years and years and years. For me, there is a strong sense that if you have certain privileges, you also have responsibilities and duties.”

She quickly qualifies this.

“But I don’t, by any means, want to imply that what I do is also what others should do. I really don’t expect parents to not help their kids given our conditions. I think, in our context, it is reasonable for parents to give their kids tuition and to supervise their homework.”

However, she reveals that many middle-class parents have told her that her chapter on education was “difficult” to read.

“It forces them to think about what we are doing that perpetuates the system, that when we do what we think is best for our kids, it’s creating certain kinds of rules of the game that other kids can’t play.”

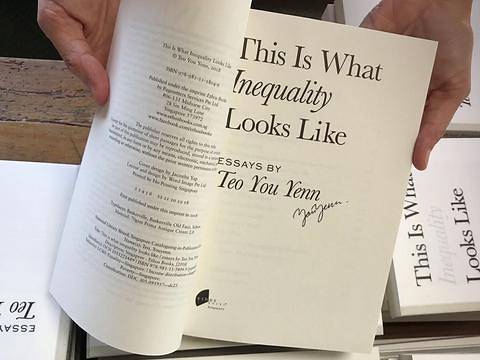

Teo You Yenn’s book, “This Is What Inequality Looks Like” has been flying off local bookstores’ shelves. (Photo: Ethos Books)

WHAT IS OUR EDUCATION SYSTEM REWARDING AND PUNISHING?

On a policy level, what is rewarded and what is punished within our education system needs looking at, she says.

She points out what Singaporeans already know and have had vociferous debates about.

“Although there is a lot of public spending on education, we also know that too much of success in schools depend on private investments from parents in education and so there needs to be significant changes within education so that the private investments are not so significant in shaping the success or failure of kids in school.”

When I point to Learning Support Programmes in schools for those who don’t have the benefit of “private investments”, she explains that while these can help, it remains challenging for the kids to catch up since the more advanced pupils continue to move forward at a fast pace.

In her book, she explains how by Primary 3, many children from low-income families are tracked and banded into lower-performing classes.

They become “well aware of where they stand vis-à-vis others”. Many become demoralised, she says.

Key to this is how the reward system is structured.

“What should be required of kids should be things that are taught in schools rather than outside of schools.

“There need to be adjustments to what is being rewarded and when it’s being rewarded because we know that in our system, being an early reader and an early writer, for example, is a huge advantage. Requiring that children, when they enter Primary One, already know how to read and write, immediately puts at a disadvantage the kids who do not have the kinds of conditions that allow them do that at that point.”

The system, she believes, works even against general developmental principles.

“Because children have such different developmental capacities, some may just not be ready to read and write. It doesn’t mean that they are incapable. Learning is partly about what people think and believe they can learn. Many of the kids I see are demoralised quickly once they enter school. These are smart kids. These are kids who have capabilities and yet they are demoralised very quickly because they are framed as ‘weak’.

When asked how to remedy this situation, she puts it simply.

“All anybody needs is time. Give it more time. We don’t have to be so quick to judge which child should be in which lane, which child should be in which kind of band. When we do that, we are losing our very precious human talent.”

EXAMS ARE DESIGNED TO “CREATE HIERARCHY”

It’s no surprise that she is a proponent of scrapping the PSLE.

“We know what exams are like and what they test. If we are very honest, we also know that the fact that we did very well in a certain exam, doesn’t mean we really learnt those things that we were able to reproduce in the exams. I would say that if you ask me now about math, physics or chemistry, or any of the other things I aced my exams in, I have to be very honest and tell you that I’m not sure I learnt that much through that process.”

She encourages experts in pedagogy to weigh in on issues such as the benefits of specialised learning and how best to teach kids so that they can develop their capacities well.

At the core of it, Dr Teo is convinced that “a huge purpose of the exams obviously is to sort and to create hierarchy”.

“It is to reward kids differently for how well they do on those exams. If we come back to merit, if we believe that it is important that we reward people for what they can do, their capabilities and the value they can therefore bring to society, then I think we shouldn’t be using these standardised exams that don’t necessarily capture those abilities and competencies.”

She is careful not to be too prescriptive in terms of offering alternatives, choosing instead to leave it to experts in the field.

She does, however, offer her experience as a university professor.

“In any given course in a university, there will be many different components of evaluation. We look at attendance, how they interact in a classroom and what they contribute to discussions in a classroom. We look at the extent to which they can collect different kinds of evidence and data to build their arguments, we look at the extent to which they are able to read things and synthesise those things in essays, we look at how they can compile different kinds of visual information into a presentation and present it in class. We try to have a range of different kinds of evaluation methods.”

A primary school student reading in the school hall. (File photo: MOE)

SUCCESS STORIES ARE THE EXCEPTION

When others say that back in the day, they too grew up with disadvantages that they managed to overcome and why can’t those in the lower-income group today do the same, she feels they are missing a huge piece of the puzzle.

“I think social context is important. I think most of the people saying that now would not expect their children to grow up like they did. We should not have double standards for our children versus other peoples’ children. Reasonable people would say, ‘Well, I grew up like that but I can also understand that today I would not expect my kids to grow up in those same circumstances’.

“But also, what kids need to thrive now is different from what kids needed to thrive even when I was in primary school in the 1980s. When I was growing up, my parents spent zero hours teaching me or helping me with homework or tuition and it was fine. I could still excel. That is the same amount of time my friends’ parents were spending on their homework – zero. That was the norm. We were playing fair with one another. If you believe that merit is important, then we were playing fair and we were playing fair to see who had more merit.”

While there are several success stories of social mobility achieved as a result of education, she claims they are exceptions.

“We do not need to close the door on any individual’s story, but we must be able to place them in the wider context of larger empirical patterns, rather than cherry-picking isolated cases of exceptions.

“In the three years when I did my research, I saw that for most low-income families, even just passing the PSLE is an achievement. Most of the kids get streamed into low tracks. A single case stands out in my mind of a child who might make it into university. These are not good odds for success, they are extremely poor ones.The doors to upward mobility through education are very much narrower for them than for kids from more affluent families.”

She doesn’t deny that today, as she looks back, she sees a period in Singapore’s history where social mobility was much more common.

MISGUIDED COMPARISONS

Growing up, she says her parents “experienced a great deal of upward social mobility”.

When she was a child, she could see “with a certain amount of money, come a lot of different choices and different opportunities that open a lot of doors”.

“I think it was an important part of my life experience growing up. I could see that I had all kinds of opportunities that my parents didn’t have and that certainly, my grandparents didn’t have. I also had certain kinds of opportunities that other members of my extended family may not have had. I think a lot of other Singaporeans experienced this.”

The question is whether that had a direct link solely to individual effort and educational policies or was it also a question of something larger.

Dr Teo points out that success today is often attributed to a person’s hard work, their ability to overcome their adverse circumstances and if they aren’t able to, it is seen as a personal failing.

It’s clear she feels otherwise.

“The huge improvement in people’s lives that we’ve seen over the last decade is partly because Singapore became so much wealthier over a very short period of time and so there was definitely an expansion in the overall wealth of the country and that expansion certainly also meant that a lot of peoples’ lives did improve. So part of the upward social mobility is not necessarily about climbing a static ladder. Part of that experience is about the fact that we grew up in those decades when Singapore experienced a wide expansion.

“That kind of radical growth in terms of development and in terms of the wealth of a country is not going to be replicated. That’s a historical anomaly. Given that we are at a different point in economic development today, that story is not going to play out for the people who are now young and who are making their way into the adult world.”

HELP IS AVAILABLE BUT CHALLENGING TO ATTAIN

A cleaner pushes his trolley in a shopping centre in Singapore. (File photo: AFP/Roslan RAHMAN)

She acknowledges the increase in social spending in Singapore but the way assistance programmes are structured often diminishes their impact and if, as a result, parents are in a state of constant insecurity, their children are naturally affected.

“A lot of how the state structures access to public goods depends heavily on their employment. The quality and quantity of services people can access is still very much dependent on that.”

In her book, she gives the example of childcare options for parents from low-income households. While others might be able to afford foreign domestic helpers and other care options, these individuals have to deal with many more limitations.

Government-linked childcare centres are heavily subsidised and affordable, but the subsidies are tied to the mother’s employment.

She calls this “a circular problem”. Without help with childcare, the women are unable to find jobs in the first place. Without stable employment, they are not able to secure a place in childcare centres.

“The underlying principle for this is that wage work is the primary form of work that should be valued and also that that’s the most important thing about being human. The problem with this is that given that people earn such unequal wages, if access to public goods is still dependent on wages, then those inequalities are not going to be reduced.”

This is borne out in many other ways when such individuals seek assistance. In her book, she explains how many of them remark that means-testing entails intrusive probing and if they can avoid it, they would, even if it means forgoing assistance.

She also points out that many of these individuals work in jobs with little stability.

They work shifts that could change often and there is often no guarantee of how many hours of work they’ll get a week. They are also seen as “easily replaceable” and their employers do not take too kindly to requests for leave to take care of their children when the need arises.

This instability, no doubt, poses challenges for parenting their children but also brings us to another critical facet of the issue.

“I see particularly through this research that there are a lot of people who work as hard as I do, who are no less than I am, but who end up with very different outcomes because their employment does not give them the wages that could help them rely on themselves.”

In past columns, she has spoken about corporations that pay some of their workers badly, and wealthier segments of the population who enjoy certain goods and services at low prices.

“We know that the benefits of the world’s wealth have become increasingly monopolised by a smaller and smaller group of corporations. Those are outcomes of specific regulations on parts of states in various different countries. Those are the outcomes of specific practices. It’s not some invisible hand of the market doing those things.”

Changing this, she feels, requires an acknowledgement on the part of states that it is something they have a measure of control over and not something that is an inevitable by-product of globalisation and capitalism.

But societal change on the part of consumers and businesses is important too and this is one of the reasons for her book – to encourage us to realise our blind spots.

IS UNIVERSAL WELFARE THE ANSWER?

Ultimately, I wonder what she thinks policymakers should be doing differently to tackle inequality as a whole.

Considering the Government’s robust narrative of self-reliance, how can initiatives be designed more effectively taking this into account?

“It’s important to pose the question differently, not in terms of, ‘Can this person afford to do this?’ We need to ask, ‘Well, what is it that every person needs?’ And as a society what do we need to do so that people can meet all these basic needs as a baseline? We can have reasonable discussions about what we can collectively agree on are basic needs.”

She is currently in the midst of research that aims to gauge what society considers “basic needs” that everyone should have regardless of their personal ability to afford them.

“Universalism in meeting fundamental needs, such as housing, healthcare and retirement security, would protect everyone in society from precarity, instead of making dignity and security dependent on private earnings and wealth.”

Arguments for universal welfare, she feels, should not be discredited outright.

“People are very reasonable in terms of thinking about what is basic for a decent standard of living. Universal welfare in this context is not a slippery slope. Empirically, I found that people value work. A lot of sociological work has shown that the value of work, the meanings people take from work go beyond the income they earn from the work. Work is a very important part of peoples’ sense of self and peoples’ sense of worth. The assumption that if you don’t make life difficult for people, they won’t work, is just not true.”

But if more were done in this regard, the rest of society too must be willing to do more.

“There needs to a serious conversation about whether taxes may be worth paying to reduce the insecurity and divisiveness that inequality inflicts on us all. This is especially given the room for more progressive taxes. The personal income tax rates for high earners, as well as wealth taxes such as estate taxes and capital gains tax are lower than in many other countries. To have this conversation across society on an informed basis, we also need the publication of more transparent and detailed information about projected revenue and expenditure.

“The countries that the world knows have done a lot better on these issues are the Scandinavian countries, Sweden, Norway, etc. I think economically, these are all places that are doing quite well. Often the argument is made that if you did a lot of these things, your economy would go bust and that’s just not empirically true.”

These countries may have a greater commitment to redistribution, but certainly a fine balance has to be struck to prevent a descent into a failed welfare state.

As we come to the end of our conversation, I ask her how she might feel if her position on issues is seen as being too idealistic and impossible to implement.

What she says next is something she feels ought to be applied to her own views too.

“Research, writing and telling stories about society are often dominated by people who are in positions of relative power. This would include politicians and intellectuals. I think it’s important that people in positions to either make decisions or tell stories, don’t tell their stories or make decisions as if their perspectives are the universal perspectives. The act of making decisions or telling stories should be one that includes the voices and perspectives of people outside that narrow class of people.”

It was why she inserted herself into her research to make it clear to readers where she is speaking from – her lenses and her blind spots – and for them to then make sense of the work and evaluate it independently.

She sees it as her “responsibility and duty” to further her research in the hopes of finding not just answers, but questions as well.

“I hope to continue to learn from people who are coming at this issue from different places, who have different perspectives and different expertise to share. Knowledge production is not a static thing. There are more things to do and more questions and more puzzles to answer.”