IN recent years, Southeast Asia has seen a surge in demand for a skilled workforce able to fill looming gaps in industries dependent on new and emerging technologies.

Unfortunately, the supply of such talents in the current labour market has largely fallen short.

As the wider Asian region deals with ageing populations and massive migratory shifts, The Economist predicted an “impending collapse” of the Asian workforce as governments struggle with developing human capital.

To strike a balance in its working populations, Southeast Asia reportedly needs to attract six million workers. By 2030, Thailand would be in dire need of workers between the ages of 15 and 64 and the same goes for neighbouring Singapore, Malaysia and Vietnam.

Trends over the past decade, however, paint a worrying picture, as close to 50 percent of Asian employers found hiring to be difficult amid a backdrop of the highest global talent shortage since 2007.

Structural problem

While there is high demand for skilled employees, graduates in the region often don’t measure up, leading to youth unemployment.

In Southeast Asia in 2017, youth unemployment was lowest in Singapore at 4.6 percent, followed by Thailand’s 5.9 percent, Vietnam’s 7 percent and the Philippines’ 7.9 percent, Malaysia’s 10.8 percent and Indonesia’s 15.6 percent.

Commenting on Malaysia’s situation recently, local politician Yeoh Bee Yin noted that the country’s youth unemployment rate is up to three times higher than the national unemployment rate (3.17 percent in 2017). For comparison, 10 out of every 100 youths are unemployed while the same is true for only three in every 100 workers of all ages.

There’s a growing skills mismatch in Asean’s labour market. Source: Shutterstock

She noted that one in four graduates has remained jobless six months after graduation.

“This implies that our tertiary institutions are not producing the workforce that is needed by the market. There is a mismatch between the supply and demand of the workforce. That is the first structural problem,” she said in an editorial.

“Growing up, we are told that a university degree is a ticket to a successful life, or at least a better life than our parents. It doesn’t apply anymore today. Many of our young people today, even with university degrees, are not earning enough to cope with the rising cost of living.”

This mismatch is real. Of the thousands of available jobs in the country, only 23.5 percent are high-skilled positions suitable for university graduates.

SEE ALSO: How are Southeast Asians today faring differently to their parents?

Earlier this year, Myra, a 29-year-old University of Brighton master’s degree holder described how she was never able to get a job that paid her more than RM3,600 (US$900) a month despite her credentials and years of experience.

“I am so, so upset and disappointed,” she said.

Despite holding degrees, many like Myra live in relative poverty: earning below RM2,700, the living wage recommended by Bank Negara Malaysia, Malaysia’s central bank.

Azzief Khaliq, who holds a Masters in Communications from Universiti Sains Malaysia, said there was little or no incentive for him to work full time as his credentials do not set him apart from those with lower qualifications.

His MA, he said, “is pointless in the workforce.”

“There seems to be an odd lull in that sort of 4 or 5-year employment experience area I find myself in, where it’s either real entry level stuff or stuff that seems to want more out of the employees than I can offer.”

Rising industries

With a combined GDP of US$2.4 trillion, Southeast Asia’s economy is ranked the seventh largest in the world and is pacing itself to rank as the fourth largest by 2050.

However, the progress is stymied by skills shortages, particularly in tech.

The Information Technology (IT) sector is one of the highest on the list of skills that are scarce.

Kimberlyn Lu, Country Manager of recruitment firm Robert Walters Malaysia, said there is a rising demand for quality candidates with niche tech skills in the region.

SEE ALSO: Are Southeast Asia’s education systems preparing workers for the future?

“IT is an industry that is rapidly growing, and candidates with niche skills, such as cloud architects, cybersecurity professionals, data mining and analytics experts for example, are not only sought-after by IT companies, but also traditional companies looking to digitalise,” she told Asian Correspondent.

“The digital economy and growth of online retail has also driven the demand for sales and marketing professionals in the e-commerce sector. Candidates with both digital and merchandising skills are also highly sought-after.”

In human resource, and legal and compliance fields, the firm has also seen companies seeking out talent who not only have specialised knowledge within their fields, but who can also act as business partners, and play strategic roles in building up businesses.

Initiatives

Malaysia’s Human Resources Minister M. Kula Segaran. Source: Facebook

Malaysia’s Human Resource Minister M. Kula Segaran, in a statement to Asian Correspondent, said the country’s youth unemployment rate was not much better or worse than those of advanced economies like Norway (10.1 percent) or Australia (13.5 percent).

“This is due to the fact that job seekers among youth are in a transition period (job-hopping) while actively searching for better and suitable job opportunities.”

Nevertheless, Kula Segaran says his government has been doing its part, including one initiative to provide jobs through www.jobsmalaysia.gov.my targeted at fresh graduates.

In the first six months 2018, a series of jobs fairs and carnivals organised by the ministry helped the placement of 95,387 job seekers, he said.

SEE ALSO: Employment: The 10 most in-demand skills for 2019

The ministry has also established a one-stop centre involving government agencies like JobsMalaysia, the Social Security Organisation (Socso) and Human Resources Development Fund (HRDF) to provide professional consultancy services for jobseeking and training.

Last year, a total of 1,694 trainees were successfully placed in jobs via the Graduates Enhancement Programme For Employability (Generate) programme that equips unemployed graduates with soft skills.

“(This includes) widening apprenticeship and industrial training programmes to increase youth employability through soft-skills enhancement dan on-the-job training programme,” he said.

In neighbouring Indonesia where youth employment remains a worrying trend, the median age of the country’s population is 28. And its working-age population as a share to the total population is fast expanding, exponentially increasing the current demand for employment.

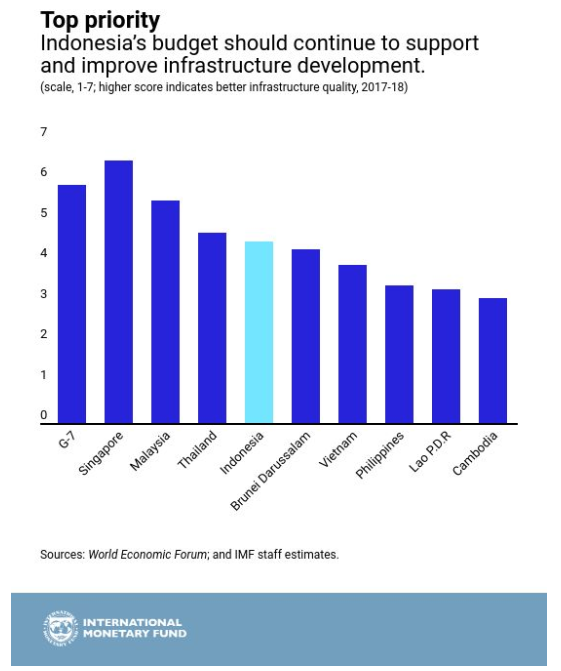

To create jobs, the International Monetary Fund has urged the government to prioritise infrastructure development to spur private investment and generate growth, which would, in turn, result in more employment opportunities.

Additionally, the IMF also suggests reducing state control and entry barriers, particularly in the power and transport sectors, as well as lowering trade and foreign direct investment restrictions to boost competitiveness.

“Emphasis should be given to improving coordination among different ministries and local governments to avoid conflicting regulations.”

The republic’s education quality also needs enhancement, which means more efficient spending by strengthening the link between compensation and performance in the education sector.