SINCE Trump’s ‘Indo-Pacific’ speech in November 2017, Japan’s strategic vision towards the Indo-Pacific region, the ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific Strategy’ (

The FOIPS is a strategic vision that primarily aims to maintain the existing international order – premised on a set of principles such as the rule of law, a free market economy, and fundamental rights – in the Indo-Pacific region.

How can Japan achieve this vision? The FOIPS is an evolutionary concept, its form constantly changing over time. Regardless, its backbone rests on the alignment strategy, which envisions “US In, China Down, Asean/India/Australia Up .”

SEE ALSO: US partnership offers alternative to Chinese investment in the Pacific

In maintaining peace and stability, it is imperative for Japan to ensure America’s strategic commitment to the region.

In particular, responding to China’s potential challenges to the existing international order is vital in the context of its strategic outreach to Eurasia, Africa, and Eastern Europe. If such challenges are perceived as threats, they are to be constrained, if not contained.

Japan’s ‘Pivot to Asia’

This, however, is not enough.

Securing the vast geographical areas of the Indo-Pacific region requires cooperation with Japan’s regional partners,

Asean is important in shaping the regional multilateral norms and legitimacy in Southeast Asia and beyond. India and Australia as democratic states are important players in safeguarding the existing international order, covering the Indian Ocean and Southern Pacific respectively.

Of course, Japan’s FOIPS framework was not created overnight.

The origin of the vision dates back to Prime Minister Shinzo Abe’s opening speech at the Sixth Tokyo International Conference on African Development in August 2016.

The speech emphasised the importance of economic development, including the need for quality infrastructure between Asia and Africa as well as sea lines of communication between “the seas of Asia and the Indian Ocean.”

SEE ALSO: ‘China model’ threatens press freedom in Asia Pacific

Abe’s personal commitment to the Indo-Pacific region can be seen through a number of his addresses over the last 10 years, highlighting that the strategy was born mainly out of Japan’s reaction to the emergence of potential obstacles put forward by China to existing international rules and norms.

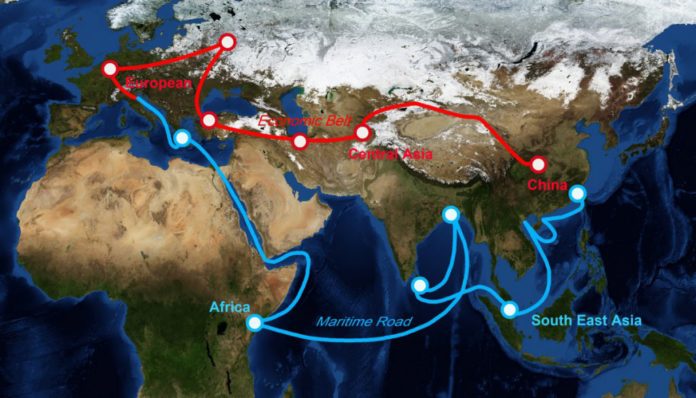

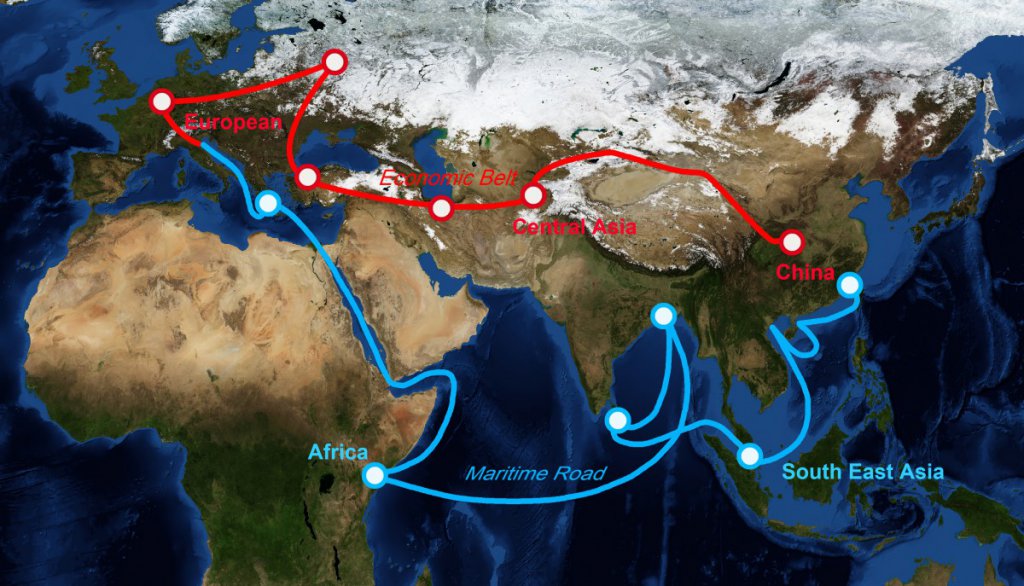

One such concern was the increasing visibility of China’s Belt and Road Initiative, which has pushed infrastructure development throughout the region since Xi Jinping’s two speeches in Kazakhstan and Indonesia in 2013.

Japan’s other worry lay in China’s refusal to abide by the South China Sea Tribunal Award promulgated in July 2016.

The core elements of the

Xi & Abe – back to ‘normal’?

Admittedly, policymakers in Tokyo are yet to clearly indicate whether the

But this is because the strategy is vague by design. Such vagueness allows Japan the flexibility in

This was well illustrated by the Japan-US Summit in November 2017 for three reasons.

Firstly, Tokyo was able to get the US on board with the concept of a ‘Free and Open Indo-Pacific’ to keep China in check.

Secondly, the two countries

Finally, they agreed to the non-exclusive nature of the strategy, which leaves Japan’s options open for cooperation with China in future.

SEE ALSO: China’s foreign policy is buying influence, but not respect

To date, the implementation process of Japan’s Indo-Pacific strategy has been relatively smooth.

The Quad, a cooperative framework between Japan, the US, Australia

On top of this, this year,

Looking ahead, however, there exist three main challenges.

First, it is imperative for Japan to ensure very close policy coordination with its allies and partners. The nature of the FOIPS is intentionally unclear, leaving room even for allies and partners to be easily misguided.

This is particularly the case for the US, as American policies towards China are becoming more competitive, even as Japan is attempting to engage with and shape China’s behaviour.

To maintain strategic consistency and avoid misunderstandings, therefore, constant and close communication is key in achieving agreed upon objectives.

Abe’s Trump diplomacy

Second, Asean’s relevance requires greater clarification.

Without clarification, other countries in the region are likely to either neglect Asean or be entangled in its slow decision-making procedure.

Third, Japan needs to identify the strategic scope of the

Ambiguity might prove helpful when responding to the uncertain nature of regional affairs, but without clarifying its scope and the means to achieve its objectives, Japan risks strategic overstretch.

SEE ALSO: Debt-trap diplomacy: Can Africa reject China’s easy money?

These are difficult tasks, but the policy’s vagueness would potentially increase strategic uncertainty in the region.

In December, Japan will issue its new National Defense Program Guidelines, which aims to strengthen its defence capabilities, including its naval power projection.

As a first step, Prime Minister Abe should explain to his domestic and international audiences the status and future of the

This piece was first published at Policy Forum, Asia and the Pacific’s platform for public policy analysis and opinion.