SINGAPORE: Life changed for Ahmed Sumon on Jan 20 last year. He had been dismantling a structure at a construction site in Tampines when he was suddenly pinned to the ground with a metal bar on his back.

He was unconscious as he was moved out of the worksite. His company sent him to a clinic at first, where he was prescribed painkillers, he said.

But after a few days, the pain was still unbearable. He got himself admitted to hospital, where an MRI scan showed he had fractured his spine.

The 30-year-old was unable to work for the rest of his time in Singapore. He returned to Bangladesh in February this year.

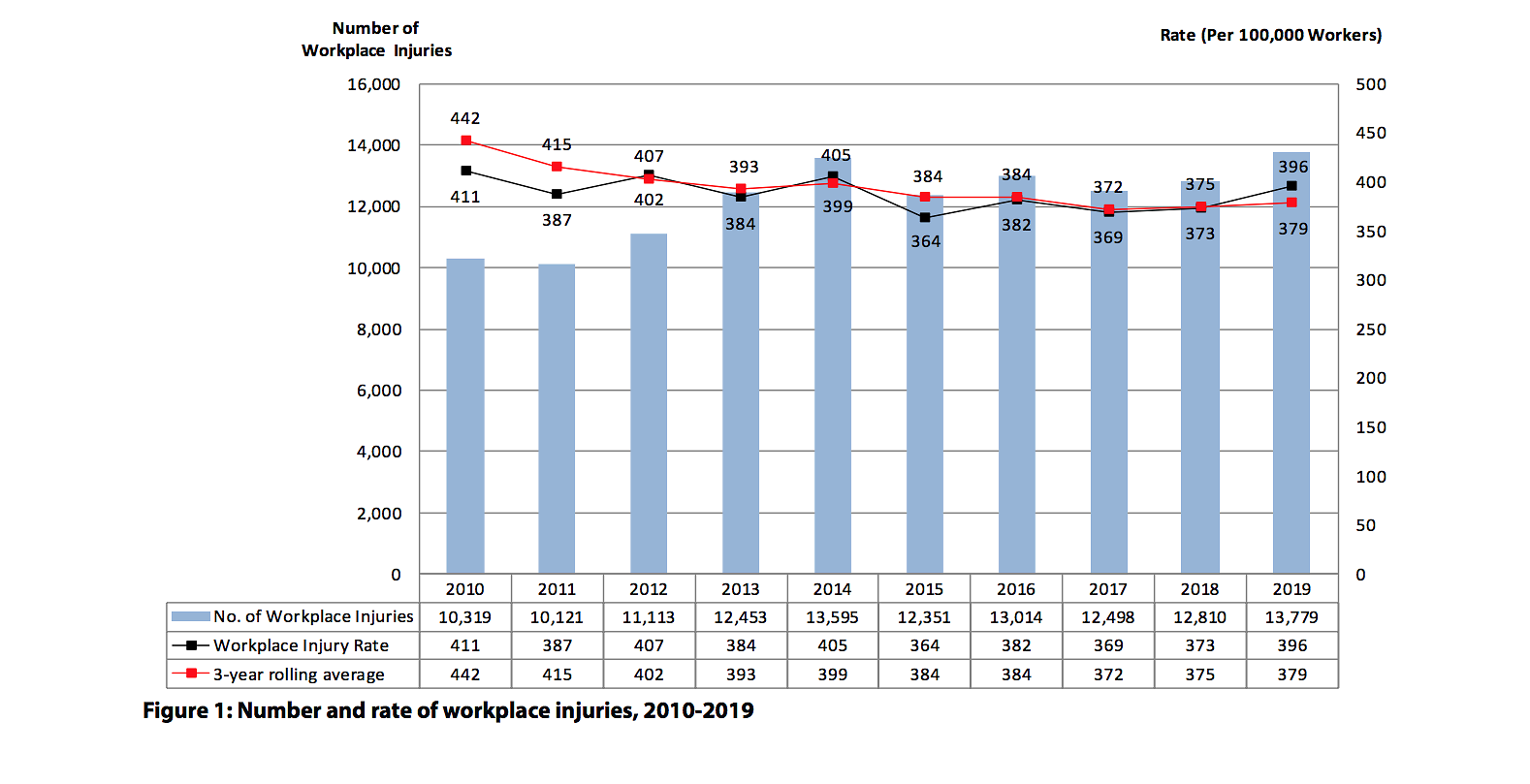

Mr Sumon is one of the 13,779 people who were injured on the job last year, according to the Workplace Safety and Health (WSH) 2019 report.

Last year’s rate of injuries was at a five-year high, with an injury – fatal and non-fatal – rate of 396 per 100,000 workers. The construction and manufacturing industries were its top two contributors.

“This is a cause for concern as every worker deserves to work in a safe and protected environment, and every worker should have the right to return home safely,” said Melvin Yong, assistant secretary-general at the National Trades Union Congress (NTUC) – a sentiment shared by construction and manufacturing industry firms and observers.

And though 2019’s workplace death rate was at its lowest since 2004, the trend seems to have reversed in the first few months of this year.

Last month, Minister of State for Manpower Zaqy Mohamad revealed that more people had lost their lives through workplace accidents so far this year compared with the same period in 2019, despite the ongoing “circuit breaker” meaning that most workplaces are closed.

READ: More fatal workplace accidents despite decline in work activities due to COVID-19 pandemic

There were 14 fatalities recorded from Jan 1 to Apr 17 this year compared to nine within that period in 2019.

Mr Zaqy called it a “worrying trend” that reinforced the need for employers and workers to press on with efforts to improve workplace safety and health.

Injured workers could experience a loss of future earnings, Mr Yong said, as well as having to bear additional costs of treatment and rehabilitation beyond what their workplace injury compensation can cover.

Among foreign workers, there is also the issue of debt.

Before coming to Singapore, most of these job seekers pay a recruitment fee to brokers in their home countries. While authorities in Singapore place strict controls over how much local employment agencies can charge the worker, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) has said that it has no jurisdiction over the fees charged by agencies in the sending countries.

Becoming incapacitated causes “immense distress and anxiety” among workers who feel helpless about no longer being able to earn money for their families back home, said Desiree Leong, a case worker at Humanitarian Organization for Migration Economics (HOME).

In addition, there are worries over how they are going to repay their outstanding recruitment fee debts, and injuries that might worsen if their employers delay treatment, Ms Leong said. Most of the workers that the non-profit sees – usually just under 150 cases a year – sustain back injuries, while others have lost fingers or their limbs crushed.

Some of the ducks that Mr Sumon bought to start his duck farm. (Photo: Ahmed Sumon)

Overseas job brokers usually collect a few thousand Singapore dollars from each worker, said HealthServe case worker Yvonne Loo, although she has met some charged a fee as high as S$10,000.

In Singapore, there are nearly a million work permit holders, as of December 2019’s official figures. Aside from the quarter of a million foreign domestic workers, the rest are typically foreigners working low-wage jobs in construction, manufacturing and shipyards.

They earn about S$600 to S$700 each month, said Ms Loo, with about 20 per cent of that amount going to pay for lodging and food.

By working overtime, Mr Sumon earned a bit more – S$1,200 a month, most of it remitted home to his wife, his unemployed father and a mum paralysed by stroke.

But having came in and out of Singapore four times since 2012, Mr Sumon said that he had racked up a debt of S$20,000 in total owed to various employment agencies in Bangladesh, which he coughed up through loans from banks and friends, and by selling his father’s farmland and cows.

Mr Sumon chose to start a duck rearing business with whatever compensation money he had left as job prospects are low in his village and ducks cost less than other poultry animals. (Photo: Ahmed Sumon).

He has managed to settle the debt, half of which came from his S$16,000 work injury compensation. Left with S$6,000, he used S$5,000 to start a duck farm business – job prospects in his village are low, especially during this COVID-19 situation, he pointed out – and the rest to look after his family of five.

DOESN’T PAY TO CUT COSTS

Workplace injuries bear heavy costs not just on a worker’s life, but on a company’s bottomline too, construction and manufacturing industry players noted.

The more the number of injured workers, the higher the costs as companies accrue stop-work orders and medical expenses, said Dr Goh Yang Miang, a former chairman of The Institution of Engineers, Singapore’s health and safety engineering technical committee.

Employers also have to bear the costs of training new workers who replace the injured party, increased insurance premiums after every injury, productivity downtime with each injury and legal fees should the worker decide to take legal action in lieu of file for workplace injury compensation, said Mr Yong.

To better protect construction workers, MOM is planning to improve the mandatory construction safety course by including experiential elements in it by 2022.

The course, which is called ‘Apply WSH in Construction Sites’, is available abroad as well.

However, the Tripartite Alliance said in response to CNA’s queries there are “currently no plans for the AWSHCS course to be conducted overseas”.

Some developers, like JTC and the Land Transport Authority, have already made it compulsory for workers to undergo a safety course that has experiential components in it before they work on their projects.

At the JTC-initiated Construction Safety School, which is operated by the SCAL (Singapore Contractors’ Association Limited) Academy, workers undergo an eight-hour class that includes two hours of simulations, which includes the experience of falling into a pit and getting electrocuted.

The participants are tested after the class on their ability to spot safety hazards and protect themselves.

Since it opened last June, 120 companies – or 2,400 supervisors and workers – have gone through the course, an academy’s spokesperson said.

“We believe that the workers are better able to retain whatever they’ve learnt when they experience what it feels like to get injured on the job,” he said.

SAFETY IS PARAMOUNT, BUT ALSO HARD TO ENSURE

Businesses acknowledged the importance of protecting their workers, but they pointed out some of the challenges in doing so.

Most times, contractors are up against tight timelines, with financial penalties imposed for late delivery, said Peter Soh of EPRO Engineering.

Schedules are often accelerated to avoid delays, while overtime is unavoidable in many projects, the electrical engineering contractor’s managing director said. This time pressure ends up potentially affecting safety performance.

Mr Soh added that because contracts are typically awarded based on price, some contractors will try to cut cost, which translate to fewer safety supervisors on site, and cheaper materials and equipment.

The suspension trauma simulator, which allows workers to feel whats it is like to fall with a harness strapped on. (Photo: Corine Tiah)

Dr Goh added that more recent construction projects are closer to other buildings and facilities in the vicinity, so there is less space at the worksite for workers to manoeuvre around equipment and machines.

Even if the company conducts multiple safety briefings, the employees also bear responsibility to be on guard at work, said Mr Soh, who has 13 employees. Less experienced workers may still lack safety judgment that is developed on the job.

Manufacturers operate in a “highly dynamic environment”, noted Singapore Manufacturing Federation’s president Douglas Foo. Employees, raw materials and completed goods are moving around production lines all the time.

“Workers themselves cannot be complacent, thinking that they are experienced in any one area and therefore cut corners which may then compromise their own safety,” he said.

Rajan Rajgopal, the chief executive of Denselight Semiconductors, said that the firm has spent more than S$100,000 on alarms and sensors that alerts workers when there is a chemical leak – the main safety risk among semiconductor manufacturers. Maintenance cost about S$20,000 a year.

The company has to install multiple systems around the fabrication plant, since one sensor only detects one type of gas at one time, he said, and semiconductor producers use several different gases in their manufacturing process.

While expensive, “it is a one-time initial cost that is worth it, as even one safety incident is more than what you want,” Mr Rajgopal said.

For Mr Sumon, one accident was all it took to change the course of his life.

He started raising ducks because as much as he wants to come back to Singapore, he is unlikely to do so as he is still unable to do any heavy lifting. He also has other concerns.

Mr Sumon outside his fledging duck farm back in his hometown in Bangladesh. (Photo: Ahmed Sumon).

“If I come to Singapore, I have to borrow money again. I’m scared (to do so),” he said.

Yet, he said, “I miss going to many places, meeting my friends.”

“I’m thinking about Singapore all the time.”