SEOUL – When the lawyer representing the woman at the centre of a scandal engulfing South Korean President Park Geun-hye met his client upon her arrival in the country from Germany on Sunday morning, he was blunt.

“I told her: ‘You are now all alone. No one will protect you, not even the Blue House’,” said Lee Kyung-jae, referring to South Korea’s presidential compound.

Prosecutors have said they are looking into whether Lee’s client, Choi Soon-sil, 60, used her friendship with Park Geun-hye to influence state affairs by gaining access to classified documents and benefited personally through non-profit foundations.

The alleged influence exerted by Choi, an informal advisor with no official government role, has baffled and infuriated many South Koreans, thousands of whom gathered on Saturday night in central Seoul calling for Park’s resignation.

The saga has dominated headlines and prompted the resignations of several of Park’s closest advisors, further weakening the president in the fourth year of a single five-year term and sending her approval rating to an all-time low.

Park, 64, has described Choi and Choi’s late father as old acquaintances who helped her through difficult times.

She said in a brief televised statement last week that she had given Choi Soon-sil access to speech drafts early in her term, apologising for causing public concern.

Choi told South Korea’s Segye Ilbo newspaper last week that she received drafts of Park’s speeches after Park’s election victory but denied she had access to other official material, influenced state affairs or benefited financially.

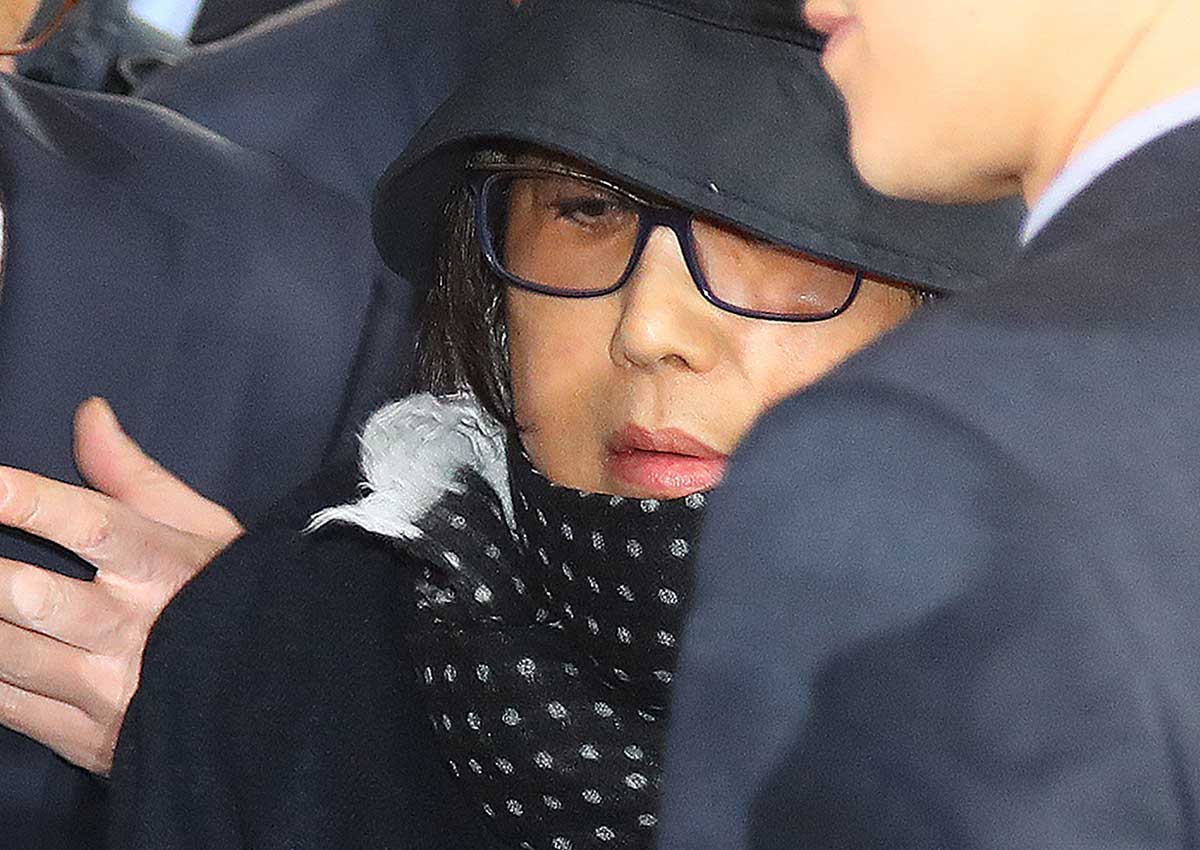

“I committed a crime I deserve to die for,” said Choi, using a Korean expression to convey deep remorse that her lawyer said is not an admission of legal guilt, after pushing through hundreds of journalists as she arrived at the prosecutors’office on Monday.

“Please forgive me.”

Choi was arrested under an emergency detention warrant late on Monday.

She arrived at the prosecutors’ office on Tuesday in handcuffs, escorted by correctional officers.

Some former presidential officials and politicians have described Choi as the most powerful person in South Korea, exerting control over Park’s policy direction and the hiring of senior government officials.

“When I worked at the Blue House, people were telling me if you get near Choi Soon-sil … you will quietly be gone,” Cho Eung-chun, who was a senior presidential secretary in 2013 and 2014, told parliament on Oct 18.

“I raised issues about privatisation of public power and opaque decision-making processes so was kicked out,” said Cho, now an opposition lawmaker.

The Blue House said it did not have any comment on the matter given there is an investigation by prosecutors.

Choi’s lawyer Lee said he expects investigators to focus on three areas: allegations about her daughter’s college admission, whether money from charitable foundations flowed into companies set up by Choi, and reported leaks of classified documents.

The allegations against Choi were first reported by South Korean media, and Lee said it was too soon to comment on whether any of them were true. “I hope prosecutors will conduct a fair, thorough investigation into the allegations,” Lee told Reuters.

PUBLIC EYE, PRIVATE PERSON

The intensely private Park, whose father led the country for 18 years after seizing power in a military coup in 1961, has long been criticised for relying on a group of close advisors who have closely guarded access to her.

Shin Dong-uk, the husband of Park’s estranged sister Park Geun-ryeong, said the president’s relationship with the Chois undermined the relationship between the sisters.

“My wife was close to Park when they lived together, sometimes as a driver, or secretary or stylist. Then after my wife got married and moved out, the two Chois wheedled their way into that vacancy,” Shin told Reuters, speaking of Choi Soon-sil and her father.

Shin, Park Geun-ryeong’s second husband, was referring to his wife’s first marriage, and said that his wife did not wish to comment on the situation.

“Nothing about President Park Geun-hye can be explained without the Choi family. They’ve become Park’s hands and legs,” he said.

ANOTHER ERA

Choi’s friendship with Park dates to an era when Park served as acting first lady after her mother was killed by an assassin’s bullet intended for her father, then-President Park Chung-hee. Five years later, in 1979, Park’s father was murdered by his disgruntled spy chief.

During that time, Park was close not only to Choi but also to Choi’s father, a religious figure named Choi Tae-min who died in 1994 and was referred to in a cable sent from a U.S. embassy official in Seoul as the “Korean Rasputin”, an allusion to the senior Choi’s perceived influence over Park.

Park told the JoongAng Ilbo newspaper in 2007 that Choi’s father had provided emotional support when she lost her parents. At the time she dismissed claims from a political rival that Choi’s father had been involved in corrupt activity.

The depth and nature of Park’s relationship with the Chois has long been the subject of speculation in South Korea.

“Rumors are rife that the late pastor had complete control over Park’s body and soul during her formative years and that his children accumulated enormous wealth as a result,” according to the 2007 U.S. diplomatic cable, which was released by Wikileaks.

The United States does not comment publicly on issues related to files obtained through Wikileaks, the U.S. embassy in Seoul said.

THE INVESTIGATION

Opposition lawmakers have alleged that Choi’s 19-year-old daughter Chung Yoo-ra, who won an equestrian gold medal at the 2014 Asian Games, enjoyed educational perks because of her connections – an accusation that stirred outrage in a country that places a high value on education.

The Ministry of Education said it would launch a special audit of the prestigious Ewha Womans University starting Monday, noting that it had found evidence that Chung had received grades without submitting papers when she attended.

Ewha’s president, who had faced student protests over an unrelated matter, resigned last month under mounting pressure from students and professors over the Choi scandal.

The Seoul Metropolitan Office of Education also found that Choi had tried to bribe high school teachers several times as she sought better treatment for her daughter and verbally attacked her sports teacher, according to a statement by the office on Thursday.

Lee, the lawyer who represents both Choi and her daughter, said Chung was in Germany, with no immediate plans to return to South Korea, and that accusations about her college admission and academic management should be cleared up in court, declining to comment further.

Lee described Choi as “tormented by what’s happening,”especially the media’s focus on her daughter.

“If she’s found guilty, she will be punished by law,” he said of Choi. “She will sincerely cooperate with the prosecutors’ investigation,” he told Reuters.