SINGAPORE: Across the Causeway, hundreds of melons have been left to rot on the fields of fruit farms and tonnes more thrown in the dumpsters, since Malaysia went into a lockdown on Mar 18 in response to a surge in COVID-19 cases there.

Under the movement control order (MCO), which is now extended till Apr 28, fresh markets and roadside stalls have been ordered to close, so demand for fresh produce has dropped dramatically, farmers said.

Malaysian fruit farmer Toh Lee Chew said orders for his melons are down 50 to 70 per cent. Unable to find other ways to sell them, he has left the melons to rot in the fields.

His brother Toh Lee Bing, who helps supply the fruits to markets and fruit stallholders, said he has had to throw away 3 to 4 tonnes of fruits from every lorry, even after donating whatever he can to charities.

The surplus situation is further exacerbated when Singapore went into a “circuit breaker” on Apr 7. The number of lorries carrying fruits from the Tohs’ farm every week into the Republic has since dropped from three to one or two.

Another fruit farmer Alvin Lo has resorted to donating a portion of his excess supplies as feed for zoo animals, in addition to giving some to charities and frontline workers.

READ: Commentary: Farmers hold key to feeding Asia amid COVID-19 restrictions

READ: Commentary: Restrictions on movements in some Southeast Asian countries to fight COVID-19 have been patchy, even scary

Malaysia’s vegetable farmers are also grappling with excess supplies that have few takers.

During the first two weeks of the MCO, farmers had to throw away hundreds of tonnes of fresh vegetables, said Mr Tan So Tiok, chairman of the association for Malaysian vegetable farmers. The abrupt implementation of the lockdown – announced less than 48 hours before it began – led to a sudden excess in supply.

Malaysian fruit supplier Toh Lee Bing says he has thrown away 3 to 4 tonnes of fruits from every lorry, even after donating whatever he can to charities. (Photo: Toh Lee Bing)

Mr Tan said that vegetable supplies sent to Singapore every day via the Causeway have decreased from 600 tonnes to 400 tonnes since the Republic’s circuit breaker measures kicked in.

But Mr Tan said the situation has now stabilised as Malaysian farmers have started to grow smaller amounts of vegetables.

The dumping of excess agricultural produce due to a drastic drop in demand as restaurants, hotels and other food outlets close is happening not just in Malaysia.

READ: New S$30 million grant to help Singapore farms speed up production of eggs, vegetables and fish

READ: Singapore aims to produce 30% of its nutritional needs by 2030, up from less than 10%

In the United States, the New York Times reported that farmers have had to dump thousands of gallons of fresh milk into lagoons, or bury one million pounds of onions or even smash 750,000 unhatched eggs every week.

Farmers in India are throwing truckloads of fresh grapes into compost heaps or feeding their cattle with strawberries since the only alternative is to let the fruits spoil, according to Reuters.

The pictures in the media reports showing staggering amounts of agricultural waste were in stark contrast to images of empty shelves and snaking queues in supermarkets in various parts of the world, where buying limits on groceries have also been imposed to prevent hoarding.

READ: The Big Read: Singapore has been buttressing its food security for decades. Now, people realise why

This disconnect between supply and demand is the result of the global food supply chains being disrupted in unprecedented ways due to the COVID-19 pandemic, said experts.

The outbreak has wreaked havoc on the supply chains as governments in many countries impose lockdowns to curb the spread of the highly infectious novel coronavirus that causes the COVID-19 disease.

Farmers cannot work the fields and truckers are unable to transport the food to markets as restrictions are being placed on people’s movements all over. With airlines grounding most of their fleet, the capacity for suppliers to export their produce via air freight has also dwindled.

A farmer in India feeding his strawberries to his cow because the local tourists that usually eat them are gone, as are the fruit vendors due to the nationwide lockdown to slow the spread of COVID-19. (Photo: Reuters)

READ: Locally grown strawberries a first for Singapore’s farming industry

Last month, Trade and Industry Minister Chan Chun Sing said the halt in production of goods in many countries as they go into lockdown during the COVID-19 pandemic, as well as disruptions to air and sea connectivity, are among the biggest challenges that Singapore is facing in maintaining its trade flow.

A recent survey among food companies in the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN) found that supply disruptions and labour restrictions were their two biggest challenges amid the pandemic.

The survey was conducted by consultancy firm PwC and regional industry grouping Food Industry Asia. “The region’s food system remains highly interdependent – and it must be recognised that disruption to any part of it will have significant unforeseen knock-on effects,” it added.

Indeed, while companies in Singapore were most satisfied compared to their regional counterparts in terms of the ability of goods to continue to move freely nationally and internationally, the supply chain disruptions have led to an increase in some food prices in the Republic, which imports 90 per cent of the food it consumes.

Grocery shoppers said certain food items, such as eggs, onions and potatoes, have seen an increase in prices by about 40 to 50 per cent since the outbreak started.

READ: New laws proposed to ensure Singapore’s food security

READ: New agency to be formed to oversee Singapore’s food safety, security

To help Singapore consumers, NTUC FairPrice chief executive officer Seah Kian Peng said that Singapore’s largest supermarket chain would keep its pledge made in March last year to freeze the prices of 100 FairPrice house brand products including rice, cooking oil, poultry and toiletries, till the middle of this year.

The supply chain disruption could have been much worse. Thankfully, China – the world’s second largest economy – had recently eased restrictions gradually all over the country and lifted the nearly three-month lockdown in Wuhan, where the COVID-19 pandemic started.

This “phasal phenomenon” of COVID-19, where different countries experience the worst of the pandemic at different times, is something to be optimistic about as it allows countries such as Singapore to have supply lines from different countries at different points in time, said Professor Paul Teng, an adjunct senior fellow at the Centre for Non-Traditional Security Studies in the S. Rajaratnam School of International Studies (RSIS).

Still, Mr Seah noted that as many countries turn to China for their supplies, the capacity of China’s containers and ports would limit the amount of food that can be exported at any one time.

READ: High-tech farms in Singapore take on cold-weather crops

READ: Commentary: Obviously, we want ASEAN to collaborate better on COVID-19

SAFETY NETS IN PLACE BUT …

Despite the upheavals, experts stressed that there are enough non-perishables, such as rice and wheat, to feed the world.

According to the US Department of Agriculture, global stockpiles of rice this year are at an all-time high of more than 180 million tonnes, with global production estimated to be at around a record 500 million tonnes for 2019 and 2020.

For the next few months, the existence of national stockpiles also means that there will be enough food to go around, such as in Singapore’s case.

Mr Chan had said earlier that Singapore has more than three months’ worth of carbohydrates such as rice and noodles, and more than two months’ worth of stockpiles for proteins and vegetables.

Food supplies at NTUC FairPrice’s Benoi Distribution Centre on March 7, 2020. (Photo: Chan Chun Sing/Facebook)

READ: The future of local farming: Balancing technology and nature

In response to queriesf, a spokesperson from the Ministry of Trade and Industry (MTI) said that Singapore has a “robust and multi-pronged strategy” to ensure the resilience of its food and essential supplies.

“This includes prudent stockpiling and diversification of sources, and also the expansion of local production,” the spokesperson said.

The ministry is also working with like-minded countries to ensure that supply chains remain intact as much as possible even while countries implement their own domestic plans to address the pandemic.

For example, Singapore has worked with Malaysia through a Special Working Committee to make arrangements for essential goods to flow between both countries, including food.

More recently, Singapore and New Zealand have also jointly signed an agreement to not impose tariffs and other trade barriers on each other. This includes export restrictions pertaining to a list of essential items.

Long before COVID-19 hit the nation’s shores, Singapore had already planned for food supply disruptions by putting in place a comprehensive strategy after the food crisis of 2007 and 2008. That was when global prices of food shot up dramatically due to trade shocks, rising oil prices and food stocks diverted to produce biofuels.

READ: ‘Closed loop’ urban farm in Queenstown tackles food waste with insects

Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli previously said that Singapore’s approach is to grow its “three food baskets”: Diversify its sources of imported food, encourage firms to grow food overseas, and expand its local produce industry.

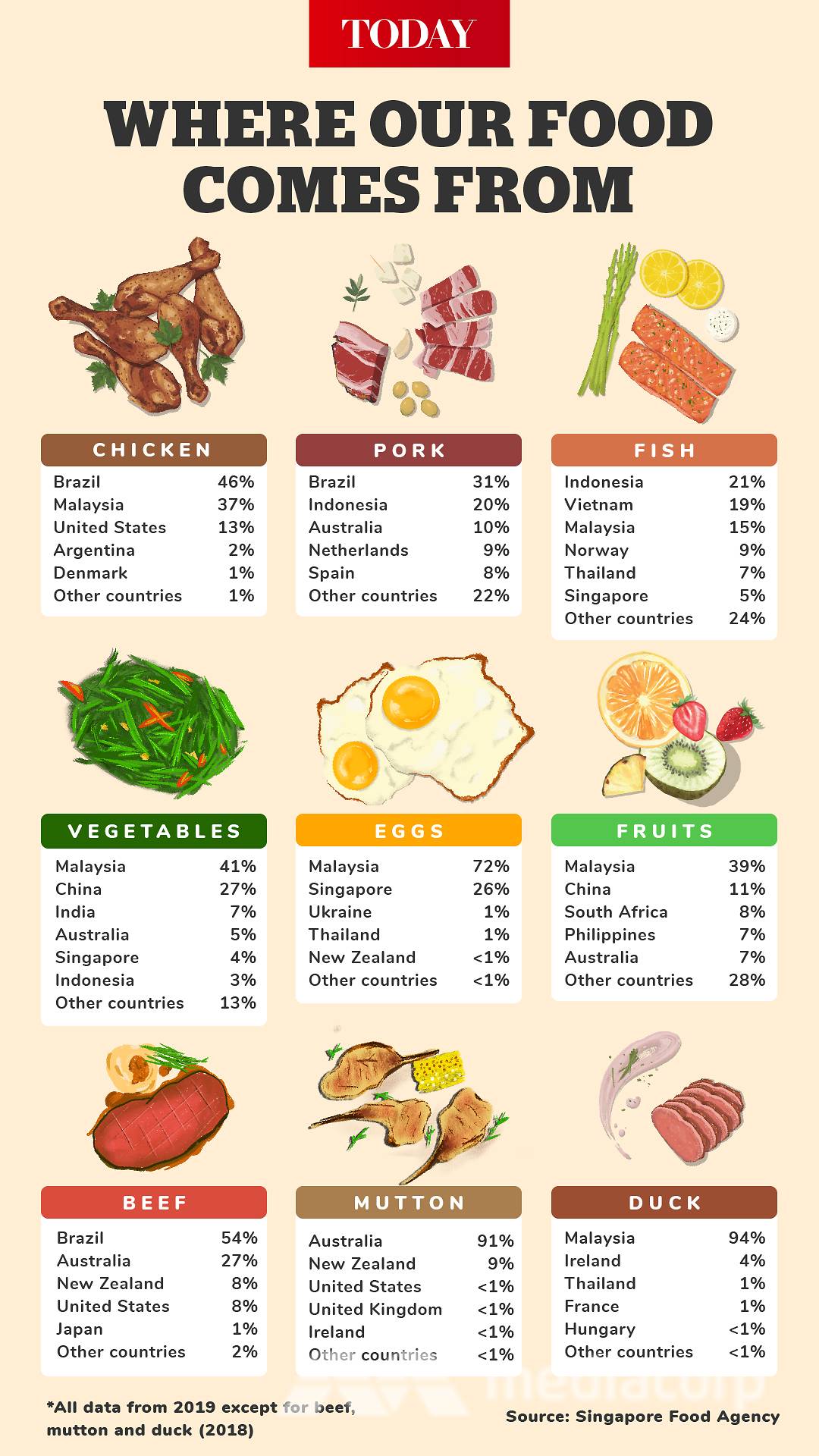

Today, Singapore’s food imports come from over 170 countries and regions, up from 160 in 2007.

This diversification of food sources did not occur overnight, and is a culmination of years of sourcing trips and prudent procurement decisions to ensure that the nation will not starve.

Despite the best-laid plans, Prof Teng pointed out that government policies to diversify food sources are premised on the fact that there is no generalised crisis, so that even if there are stoppages in one country, supply lines are still intact in another.

“The Covid-19 pandemic is a generalised crisis, affecting many countries at the same time. And the world is not prepared for a generalised crisis,” he said.

Beyond the stockpiles, some supply shortages could happen globally in the next few months, said experts and industry players.

READ: New food farming federation to tackle manpower, productivity challenges

READ: Commentary: Can farming be a success story for Singapore?

With farmers and workers staying home either due to movement curbs or fears of being infected with COVID-19, the normal production capacities of farms and food processing factories have been reduced.

For example, some meat-packing plants in the US have been shut down after their workers were infected, said Mr Alex Capri, senior fellow at the National University of Singapore (NUS) Business School.

Closer to home, Mr David Tan, president of the Singapore Food Manufacturers’ Association (SFMA), said food importers here are worried that lockdowns in Thailand, Vietnam and Myanmar might affect the operating capacity of farms in these countries.

A delay in planting and harvesting due to a lack of manpower caused by a lockdown may affect the farms’ grain yields, such as rice, which will eventually affect the total supply.

“These are seasonal crops. A delay of two to three months might mean we have fewer crops in a year … This is one of the deep concerns,” said Mr Tan.

READ: Singapore has months’ worth of stockpiles, planned for disruption of supply from Malaysia for years – Chan Chun Sing

READ: Purchase limits imposed at FairPrice supermarkets on vegetables, rice, paper and other products

SUPPLY-DEMAND DISCONNECT

The more complex problem though, experts say, is the disconnect between supply and demand.

Supply and demand for food is not fully synchronised and will never be as it is dependent on market forces, said Prof Teng.

“There is always a time lag,” he said, which is why supplies cannot move fast enough to keep up with the drastic changes in demand due to the pandemic.

A lot of food that has been dumped was grown for the purpose of supplying to the food and beverage (F&B) industry, hotels, schools and airports – all of which saw a sudden sharp drop in demand when lockdowns and border closures were imposed.

While demand from supermarkets is surging, demand from hotels, restaurants and other food services is down 50 to 80 per cent. (Photo: Ooi Boon Keong/TODAY)

The Big Read: Panic buying grabbed the headlines, but a quiet resilience is seeing Singaporeans through COVID-19 outbreak

READ: Commentary: Singaporeans queued for toilet paper and instant noodles – there is no shame in that

Because of this time lag, food is being produced based on old production schedules, said Mr Capri, and many farmers end up not being able to move these items to where demand has shifted to – that is, the supermarkets and homes.

“You are going to have a surplus and the food is going to end up not going where it needs to go,” he added.

The problem is further compounded by the reliance on traditional transportation links, such as air and sea, which have been severely disrupted as global trade and air travel grind to a halt.

“What is necessary is to take it to the consumers through the established supply chain. If disrupted, then new supply chains will have to be established very quickly,” said Dr Cecilia Tortajada, senior research fellow at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy’s Institute of Water Policy.

Commentary: COVID-19 emphasises the importance of Singapore’s free trade agreements

READ: Commentary: COVID-19 could redefine Singapore’s place in the global economy

WHAT CAN BE DONE IF PANDEMIC DRAGS ON

The challenge of ensuring adequate food supply has not become serious yet, said Prof Teng. But he warned that this may change depending on how long the pandemic drags on, and whether worldwide lockdowns continue to restrict the movement of farmers and food transporters.

“If this continues, it definitely would have an impact on the availability of agricultural produce and the transport of agricultural produce,” said Prof Teng.

One way to get around this problem for the longer term is to process the perishable food so that it can be kept longer, he suggested.

Fresh milk could be made into milk powder and exported, or fresh blueberries could be converted into blueberry jam.

However, he noted that many rural villages where the farms are located are not equipped with food-processing plants.

“If the crisis drags on for months and months, places which produce agricultural products may have to start thinking ‘should we go into food processing?’” Prof Teng said.

Another solution is to build up more local food sources, said Mr Capri, a point which FairPrice’s Mr Seah also highlighted.

Singapore, for example, has set a target of growing 30 per cent of the food it consumes by 2030. Home-based producers now meet less than 10 per cent of Singapore’s nutritional needs.

Both Mr Capri and Mr Seah said the COVID-19 pandemic has definitely accelerated plans for food localisation here and elsewhere around the globe.

READ: Demand for frozen food, freezers spikes amid COVID-19 pandemic

HOW AFFECTED SINGAPORE WHOLESALERS ARE ADAPTING

As a city-state that imports most of its food, the disruption in food supply chains across the globe would no doubt have an impact on food wholesalers and distributors in Singapore.

While demand from supermarkets is surging, demand from hotels, restaurants and other food services is down 50 to 80 per cent, said SFMA’s Mr Tan.

“This is also causing a lot of unbalanced demand,” he added.

As a city-state that imports most of its food, the disruption in food supply chains across the globe would no doubt have an impact on food wholesalers and distributors in Singapore. (Photo: Yong Jun Yuan/TODAY)

Distributors interviewed say they have had to cut down the volume of supplies imported into Singapore, look for new sources and in one case, totally transform their business model in response to the fast-changing situation.

With 80 per cent of his food products imported from Malaysia, Mr Anthony Lee, manager of Yee Lee Oils and Foodstuffs, said his company has not been able to receive his stocks in time, causing him to cancel some earlier orders from minimarts and supermarkets.

His company brings in packaged food items – such as instant noodles, cooking oil, mineral water, canned food, curry paste, and some sauces – and distributes them to hotels, restaurants and offices, as well as supermarkets.

As several of the factories he gets his supplies from have lowered production capacity to 30 to 50 per cent due to a shortage of workers, Mr Lee had to start sourcing from other factories in Malaysia, and is now trying to get suppliers from Thailand.

One problem he faces is that packaging materials, such as plastic bottles and tinned cans, are not deemed essential in Malaysia. Hence, materials for packing the food are in short supply, which in turn affects the food supply.

READ: Singapore, New Zealand committed to maintaining open supply chains amid COVID-19 situation

The amount of supplies which he receives has gone down by 40 to 50 per cent, with stocks in his warehouse able to last for about one more week.

“Now anywhere I can find raw materials, I just take as much as possible. Even if it only fulfils only 20 to 30 per cent of my order, I also take,” said Mr Lee.

On the other hand, he has a few thousand dollars worth of food supplies meant for hotels, restaurants and other food services sitting idle in his warehouse, as demand for those products has dropped.

While the products are the same, the supplies meant for these businesses are packed in large tin cans or large bottles that are not suitable for consumers, and hence he is not able to divert them to supermarkets.

“The demand suddenly switched … I can’t react because normally we forecast three months ahead. The change is too fast. I don’t know how to manage,” said Mr Lee.

While the majority (55 per cent) of his stock used to be for the F&B sector and hotels, now up to 75 per cent goes to supermarkets.

For Mr Justin Chou, chief executive officer of Glife, the sudden disruption meant that he had to quickly change his company’s business model – from supplying fresh vegetables, fruits and eggs to the F&B sector through e-commerce, to selling directly to consumers.

“It took three days to go from a business-to-business model to a business-to-consumer model,” he said, which included building a new website for consumers and setting up e-payment facilities.

Infographic: Samuel Woo and Anam Musta’ein/TODAY

While demand from the segment which he originally served has fallen by 70 per cent, he said that consumers ordering from his e-commerce website has doubled every single day since its launch on Apr 7.

From fulfilling 35 orders on the first day, his company now has to fulfil over 100 orders every day and they are looking to increase the delivery slots to more than 200 next week.

“Last time I delivered to shopping centres. Now I go to neighbourhood estates,” said Mr Chou.

The other difference is that his workers would pack the fresh vegetables coming in bulk from Malaysia and China in smaller packaging.

Mr Chou also had to cut down on the import of luxury food products from Australia and Europe via air freight, and focus instead on bringing in more essential items from Malaysia and China.

“I start to sell more rice, rather than sell avocado,” he said.

READ: Commentary: Eating less meat could help the environment and our health – so what’s stopping us?

READ: Commentary: Add more plants, and less meat to your meals. Here’s why

He added that 70 per cent of his supplies are now delivered to consumers and supermarkets, and 30 per cent to the F&B industry – a reversal from before.

Mr Tai Seng Yee, executive director of Zenxin Organic Food, faced a similar predicament, where he had to halve the products normally brought in by air, such as organic grapes and broccoli from Australia.

His company sources organic vegetables and fruits from Malaysia and further afield, and then sells them directly to consumers through its website or distributes them to supermarkets.

WIth the grounding of most airplanes around the world, air freight costs have gone up significantly. Thus, it was no longer feasible to sell some of these products in Singapore as they would have to pass down some of the costs to consumers, who would find the prices too high, Mr Tai said.

SFMA’s Mr Tan said that food transported via air used to be able to piggyback on passenger flights which have now been almost obliterated.

“Goods flown into Singapore are facing a drastic increase in freight charges as they have to especially engage planes to fly in provisions,” he noted.

Lockdowns worldwide have also led to delays at ports and a shortage of containers, Mr Tan said, contributing to higher logistics costs for food supplies brought in by sea.

Wholesalers say that the costs they incur in bringing food into Singapore have gone up due to an increase in transportation charges. Mr Chou estimates his costs to have gone up by about 30 per cent.

READ: Commentary: Is Singapore’s decades-long shift away from agriculture about to take a U-turn?

IMPACT ON S’PORE CONSUMERS

The disruption in the food supply chains and the increase in logistics cost would translate to higher food prices for consumers in Singapore.

Already, prices of certain food items, such as threadfin and squid, have increased by 40 per cent, shoppers told TODAY.

Mrs Jade Sng, who shops at the wet market and FairPrice every weekend for her groceries said that the price of eggs has gone up from S$3.90 for 30 eggs to S$5.50.

One kilogram of onions used to cost about S$2 but it is now about S$4.50.

Around 26 per cent of the hard shell eggs in Singapore are produced locally. (Photo: TODAY)

With the global food supply chains now upended due to COVID-19, experts and industry players noted that consumers here would definitely be impacted, no matter how much Singapore has diversified its food sources.

FairPrice’s Mr Seah, who is also a Member of Parliament for Marine Parade GRC, said consumers would have to adjust and accept the fact that they may not be able to get their favourite brand of eggs, for example.

While eggs sold here are now mostly sourced from Malaysia, Mr Seah said FairPrice is looking into getting eggs from countries which the supermarket cooperative has not considered before due to high costs.

“Don’t be surprised if some time from now you find eggs from Ukraine coming in,” he said.

Last month, Mr Chan noted that given the dynamic global situation where there is news about a country or city putting up tighter controls every other day, Singaporeans must be mentally prepared for food prices to go up due to the constant disruptions in supply.

Mr Chan added that at the same time, Singapore and its people can take steps to ensure that food prices here are stable – that is, it only fluctuates within a certain range.

Singaporeans can be more open to other alternative food sources, as well as remain calm and not panic-buy. The country can also choose to diversify its food choices even when the situation is normal, he said.

READ: Commentary: Clean meat – the next big thing in Singapore’s push towards agriculture?

READ: Commentary: Meat eaters think going vegan a good idea but will be unenjoyable and inconvenient

Some shoppers like Mrs Sng have already started to make some adjustments.

Mrs Sng said that while she used to buy russet potatoes from the US, their price has gone up from S$2.50 to S$4.50 for 1kg.

She has turned to cheaper potatoes from Bangladesh that cost slightly over S$1 for 1kg. But these are not as good as the russet potatoes for making mashed potatoes, she noted.

“I probably won’t eat mashed potatoes for a while,” said the 66-year-old lecturer.

While she used to plan her meals and head out to the market to buy her food, she now makes decisions about what to cook on the spot, based on the prices of available food in the market.

“I’m not too alarmed, I expected the price increase,” she said.

Noting that some Singaporeans have been “living in excess”, she pointed out that this could be the time for them to be more aware of food waste.

“When prices go up, we really are careful with what we buy,” she said.