SINGAPORE: When 28-year-old Amanda Poh was bitten by mosquitoes earlier this month while having after-work drinks at a bar, dengue fever was the “furthest thing from her mind”.

About a week later, she was down with a 40 degree fever and experienced bouts of nausea. Even then, she thought it was food poisoning.

But the fever refused to go away. Upon advice from a general practitioner, she went for a blood test at Changi General Hospital and the results confirmed she had dengue fever.

“Dengue always felt like a ‘it will happen to someone else but not me’ kind of thing, so it was a huge shock to find out that I had this virus,” said Ms Poh, a communications executive.

Recuperating at home, it took about a week for her fever to break, and rash to subside to a “twinge” though it is still visible on her arms and legs.

While Ms Poh believed that she had contracted the virus at the bar, she was not 100 per cent sure. “I live near a dengue hotspot (in Pasir Ris),” she said.

While her mother and neighbours also keep potted plants, her family is “disciplined” in ensuring bamboo pole holders and potted plants do not have stagnant water in them. “And we do not have buckets or pails (at home) that store water throughout the day as well,” she said.

READ: About 900 households fined between January and May as NEA calls for ‘collective effort’ to tackle dengue surge

Mosquito breeding in a porcelain cup (left) and a dish tray. (Photos: National Environment Agency)

For 64-year-old Toh Beng Chye, who lives at one of the blocks in Chai Chee Road — a high-risk dengue cluster — ensuring that there are no breeding spots has always been a priority in his household.

“I have a five-year-old grandson, so I am particularly aware of breeding spots. We always make sure to put on a mosquito patch when we are out. Sometimes, when I am walking around the neighbourhood and see containers of water left for stray dogs and cats, I will throw out the water too,” said the retiree in Mandarin.

Despite his best efforts, Mr Toh was unfortunately stricken with dengue fever last month.

For a few days, he was “bedridden with excruciating bone and joint pain”.

I had no appetite at all.

“I never thought I would be the one to get it, even buying 4D (lottery) also not that lucky,” he joked. “It just shows that you never know.”

READ: Weekly dengue cases in Singapore spike to highest in more than 3 years

The experiences of Ms Poh and Mr Toh reflect just how enigmatic dengue fever can be — almost impossible to trace and at times, tricky to diagnose, and hard to guard against.

Its symptoms, often in the form of a raging fever and a rash known as petechiae, usually appear days after the patient has become infectious — in that time, any mosquito which bites the infected patient will then also carry the virus.

The dengue virus also has four known strains or serotypes. While infection with one strain appears to provide immunity against that one serotype, evidence points towards increased risk of severe symptoms upon subsequent infections by the other three strains.

The existence of these strains is one reason why dengue continues to be a perennial problem, especially in places like Singapore, whose tropical climate — abundant rainfall, high humidity and temperatures — creates an ideal breeding ground for mosquitoes.

A worker fogs a community playground at a new Zika cluster area in Singapore on Sep 1, 2016. (Photo: Reuters/Edgar Su)

BACK WITH A VENGEANCE

Dengue is endemic to Southeast Asian countries. Transmitted by the striped Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, it affects thousands of people in the region each year, both in rural and urban areas.

This year, the number of infections is reaching highs across the region.

In Singapore, the dengue virus is back with a vengeance.

In 2017, dengue infections in Singapore fell to a record 16-year low with 2,772 cases. Last year was also a lull year, with a total of 3,285 cases.

The picture looks a lot different this year: As of Jun 15, there were already a total of 5,184 dengue cases, more than the whole of last year.

Dengue has also claimed five lives less than seven months into the year — the most recent one on Jun 14 — tying with the total last year.

The weekly number of dengue cases also soared to a new three-year high — a total of 467 dengue cases were reported in Singapore in the week ending Jun 15, based on the latest figures from the National Environment Agency (NEA). In March 2016, weekly number of cases peaked at 637.

The scourge shows no signs of abating, as the NEA expects more dengue cases in the warmer months ahead.

Singapore has weathered several dengue epidemics, more recently in 2005, 2007 and 2013.

A total of 14,209 and 8,826 dengue cases were recorded in 2005 and 2007 respectively. But the largest outbreak happened in 2013, when more than 22,000 people were infected, and eight died.

The number of cases so far this year is worrying as it signals that Singapore could be heading towards another dengue outbreak.

READ: 379 dengue cases recorded in late-May, highest since March 2016: NEA

Associate Professor Ng Lee Ching, who is the director of NEA’s Environmental Health Institute (EHI), boiled down dengue transmission to three main factors: The Aedes mosquito population, the strength of the virus, and immunity of the general population.

The Aedes mosquito population has been increasing — growing 25 per cent from March to April — with the majority of breeding sites found in homes, said Assoc Prof Ng.

“Herd immunity is also generally low in Singapore, and could have further weakened given that there was a low incidence of dengue cases in the last two years,” she added.

Comparing the epidemiological trend of 2004 to 2012 (first cycle) and 2013 to 2017 (second cycle), researchers from the NEA, EHI, and the School of Biological Sciences at Nanyang Technological University observed that there is a cyclical epidemic pattern associated with a switch in dominance of the first (Den-1) and second (Den-2) strains of the virus.

The “often synchronised peaks and troughs” of dengue in the region “suggest the influence of environmental factors, among many others, in shaping the epidemiology of dengue”, the researchers wrote in a quarterly health bulletin published by the Ministry of Health (MOH).

File photo of an Aedes aegypti mosquito. (AFP/Miguel SCHINCARIOL)

HOW CLIMATE CHANGE AFFECTS DENGUE

One of these environmental factors has been in the spotlight: Temperature.

A study published about two weeks ago suggested a link between rising temperatures and an increased risk of dengue transmission.

Published in the journal Nature Microbiology and reported in The New York Times on Jun 10, the study warned that climate change will exacerbate the spread of dengue fever.

Warming temperatures help expand dengue’s range because as it gets warmer, mosquitoes can thrive in more places where they could not previously. Warming temperatures also shorten the time it takes a mosquito to become a biting adult and accelerate the time between when a mosquito picks up a disease and is able to pass it on, said experts.

“If it’s cool, (the time required) for the mosquito to become infective may be 10 days to 14 days, but if it’s warm, it could take three to four days,” said Assoc Prof Ng. “That difference may be very little, but to a mosquito, in terms of its lifespan, that is very long.”

The study predicted that dengue risk will increase in southeastern United States, coastal areas of China and Japan, and inland regions of Australia, based on researchers’ analysis of climate change data, urbanisation, as well as resources and expertise available to control the virus.

Overall, the study predicts 2.25 billion more people will be at risk of dengue in 2080 compared to 2015, bringing the total population at risk to over 6.1 billion — or 60 per cent of the world’s population.

This spike will be largely driven by population growth in already endemic areas, as opposed to the spread of the virus to new populations — emphasising the increasing public health burden which many dengue endemic countries are likely to face.

Last year, Minister for Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli also highlighted the impact of climate change on dengue.

“With global warming, we can expect the dengue situation to worsen. Higher temperatures mean more conducive conditions for the proliferation of the mosquito vector across larger land areas, and faster replication of the virus in mosquitoes,” he said at the opening ceremony of the Asean Dengue Day Workshop in June 2018. He added:

Moreover, Singapore’s position as a global hub heightens the risk of cross-border importation of other mosquito-borne diseases such as zika, chikugunya, yellow fever as well as unknown diseases that may yet emerge in future.

Some experts said the study has little relevance to Singapore, since the Republic already has “near-ideal conditions for dengue transmission”. But most of them noted that the link between climate change and dengue could still have several consequences for Singapore.

For one, the virus could evolve to be “fitter”.

Minister for the Environment and Water Resources Masagos Zulkifli. (File photo: TODAY)

“An increased circulation of dengue virus would provide even more opportunities for the virus to evolve,” said Professor Ooi Eng Eong, deputy director of the Emerging Infectious Diseases (EID) Programme at Duke-NUS Medical School.

Prof Ooi said recent research findings have shown that “even small number of genetic changes can have a large impact on the fitness of dengue virus to spread through populations”.

Strains of dengue virus with increased fitness would then spread more effectively and thus increase the likelihood of outbreaks — not only within a region but transnationally.

Taking into account “Singapore’s strategic location as a trade and travel hub”, it is only logical to expect new strains of dengue virus to be introduced here even if they had evolved in different parts of the world, Prof Ooi added.

Global warming could also change the urban environment in Singapore — which is good news for the city-loving Aedes mosquito.

It has been established that the Aedes mosquito breeds predominantly in artificial containers found in human habitats. It also rests in cool and dark places indoors, has a flight range as far as 300 metres, and can traverse high-rise buildings.

“Building design may change in response to warmer temperatures, increased risk of floods and heavy rains. Aedes aegypti is well adapted to the urban environment and some of these adaptations to global warming could be favourable for Aedes aegypti to thrive,” said Prof Ooi. “Thus, while disease forecasting is still imprecise, these possible outcomes should be taken seriously if we want to avoid even worse epidemics in the future.”

‘CLEVER’ VIRUS THAT IS TOUGH TO BEAT

There is also a possibility that a change in the strain of the dengue virus could lead to an increase in the number of cases, said Professor Tikki Pang, a visiting professor at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy (LKYSPP).

Since 2016, the current dominant strain here is Den-2.

This is a change from the dominant strain during the 2013 outbreak, when it was Den-1.

Assoc Prof Ng noted that the change in strain could mean that a section of the population is no longer immunised. But given that Den-2 has been dominant since 2016, this was not a strong factor behind this year’s spike in dengue cases.

With the multitude of factors that could influence the spread of dengue, it is not surprising that the mozzie menace remains a thorn in Singapore’s side despite the relentless efforts to combat it.

Every year, a national dengue prevention campaign is launched on the island, where mayors, grassroots advisers and volunteers engage residents to increase their awareness about dengue prevention and vigilance. This is in addition to various measures to control mosquito population and eradicate breeding spots.

But the increase in dengue cases this year prompted a lecturer to ask if Singaporeans have become indifferent to mosquito-borne public health threats, and whether efforts to tackle the dengue problem are inadequate.

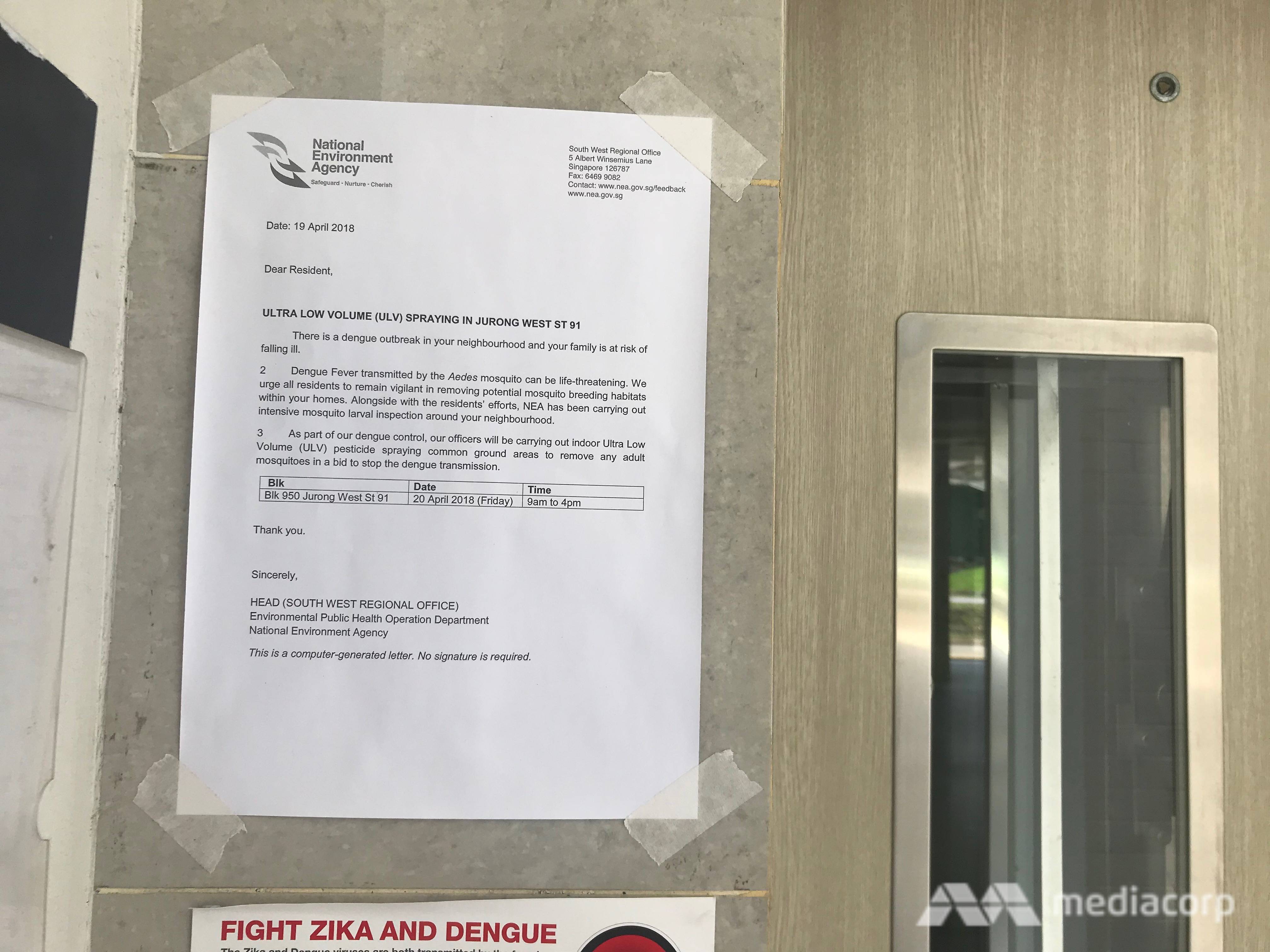

A notice informing residents of dengue control operations in the cluster. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Singapore Management University law don Eugene Tan wrote in a commentary in TODAY:

Despite stepped-up inspections and having a predictive model to help forecast dengue incidence, our national pre-emptive response to impending dengue outbreaks appears to have limited effectiveness.

Nevertheless, Members of Parliament (MPs) and residents interviewed felt that dengue awareness in Singapore is not lacking.

At his Admiralty ward in Sembawang Group Representation Constituency (GRC), MP Vikram Nair spreads the message on the importance of dengue prevention during his walkabouts, and NEA also does outreach at community events.

He said that his residents were generally “aware” of dengue prevention methods and the steps to take. “Because children are reminded so often in school, they are especially familiar with the steps of the mozzie wipeout,” he said.

Mr Tan Chuan-Jin, MP for Marine Parade GRC, said the education efforts do not stop even in the “off-peak seasons”.

“There is always a fear of complacency because of fairly successful management. It is human nature,” said Mr Tan, who is also Speaker of Parliament. “Hence, the education and awareness efforts by NEA, HDB, Town Council and the grassroots have always been on-going. We know that dengue can have serious consequences and we want to remind our residents.”

For Tanjong Pagar GRC MP Chia Shi-Lu, one particular challenge which he faces at his Queenstown ward is that there are “many residents who have very green fingers and are into horticulture”.

While this means “lots of beautiful plants along the common corridors and flats, these are also a potential source of breeding for mosquitoes”, he noted, adding:

As an adviser to this community, there is a very fine balance, very tough balance sometimes … we want to make sure that we don’t expose our community to additional risk of mosquitoes breeding. And yet we do not want to (hamper) the pursuits of our residents too much.

Still, he was quick to add that dengue awareness is “quite high” in his ward. He added:

Those who have plants show me that they know how to do the mozzie wipeout … From my interactions with residents, most do know that it can be deadly, especially in elderly or perhaps the young.

But Assoc Prof Ng pointed out that there is still a gap “between awareness and action”. In the fight against dengue, “we are only as strong as our weakest link,” she stressed.

Prof Pang reiterated that it is a “very clever virus” which is always one step ahead. It is “ just impossible” to accurately predict its growth and spread, he said.

“It’s not because of a lack of effort or complacency of the people, we still don’t know enough of the virus and it seems like it always has tricks up its sleeve,” he added.

Nurses lay a mosquito tent over a hospital bed. (Photo: REUTERS/Edgar Su)

A NEVER-ENDING BATTLE

Given the obstacles Singapore faces in eliminating the mosquito menace, what more can be done in this never-ending battle against dengue?

While the ongoing Wolbachia trials are regarded as one of the most innovative methods, the NEA has previously said they do not amount to a “silver bullet”.

“Going back to the basics” is essential — individuals have to make sure they clear stagnant water and eliminate breeding spots, said Assoc Prof Ng.

“It all goes back to source control… (It is about) good housekeeping, throwing out stagnant water. These mosquitoes like (to breed in) artificial containers,” she said.

Even so, source control alone cannot eliminate dengue outbreaks, said Prof Ooi.

“History has taught us this lesson,” he added. “Even with the Aedes aegypti eradication effort in the Americas that successfully eliminated yellow fever and dengue for a brief period, Aedes aegypti rapidly re-populated tropical and subtropical regions in the Americas once the programme stopped, due partly to the high cost and hence non-sustainability of the programme.”

Prof Ooi and Prof Pang both cited the potential of a safer and “more effective” dengue vaccine to improve the population’s chances against the virus. And it will continue to be a battle on multiple fronts.

“Dengue prevention needs more effective tools to be used in concert with vector control if we are to reduce the risk of outbreaks,” said Prof Ooi. “New tools such as vaccines, drugs and introduction of to either reduce mosquito population further or render mosquitoes resistant to infection by dengue virus are all needed.”

Accelerating the development of such tools is of utmost urgency, he reiterated.

MULTI-PRONGED EFFORTS TO FIGHT DENGUE

In Singapore, a slew of measures has been rolled out by the authorities to curb the spread of the Aedes aegypti mosquito while building a robust outbreak management system. Here are some of the key initiatives:

PROJECT WOLBACHIA

Dubbed as one of the most innovative methods currently, the project involves infecting male Aedes mosquitoes with Wolbachia bacteria, so that when they mate with females, the latter’s eggs do not hatch. Wolbachia-infected males also do not bite.

The NEA first began small-scale field studies in Braddell Heights, Nee Soon East and Tampines West in 2016, which led to a 50 per cent suppression of the Aedes mosquito population.

Male Wolbachia-carrying Aedes aegypti mosquitoes are released at various sites in Singapore under Project Wolbachia. (Photo: Angela Lim)

Nevertheless, the first phase of the study threw up unexpected challenges. It was found that Aedes aegypti mosquitoes from surrounding areas moved easily into the three chosen sites, thwarting plans for Wolbachia-infected Aedes to mate with females.

Also, there were insufficient numbers of male Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes that reached higher floors of some housing blocks. This hampered suppression efforts at high-rise blocks.

Researchers went back to the drawing board, further refining their release and deployment strategies. In April last year, the NEA began its second phase of field studies, releasing male Wolbachia-Aedes mosquitoes at higher floors, in addition to releases at the ground floor.

This time, the results improved: The mosquito population in a Tampines West study site was reduced by 70 per cent, while the population in Nee Soon fell by 80 per cent.

The NEA then expanded the Tampines West and Nee Soon East study sites — with more households taking part — to suppress the mosquito population over larger areas.

Project Wolbachia is now in its third phase, where the NEA is attempting to determine if the reduction of Aedes aegypti mosquito populations can be sustained over a period of time, and in larger areas.

While successful in reducing Aedes mosquito population, a drawback of the Wolbachia method is that it could be costly and difficult to scale up.

Prof Pang said: “There is a lot of uncertainty when you try to do it islandwide, it doesn’t mean that just because it works (at the test sites) it’ll work in other parts of Singapore.”

Each area has to be studied before the release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes, he noted.

“Then, there is the logistical issue of where you release them. Not all HDB estates are the same… there are houses in landed areas, and areas with a lot of vegetation,” he added.

Moreover, areas in Singapore have “microclimates” where the weather in one part of the island differs from the other. This affects the timing and schedule of the release of Wolbachia mosquitoes.

On the issue of cost, Prof Pang pointed out: “You have to raise enough of these Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes.”

GRAVITRAPS

The NEA also deploys gravitraps — black cylindrical containers with sticky surfaces — which attract and trap female Aedes aegypti mosquitoes looking for water surfaces to lay their eggs.

When deployed across an area, Gravitraps can also provide an indication of the Aedes mosquito population in the vicinity.

Currently, NEA officers routinely carry out inspections for mosquito breeding at landed housing estates, but this is highly resource-intensive.

This year, the NEA will progressively deploy about 14,000 Gravitraps across the island in areas such as landed housing estates and newly completed HDB blocks. This will allow its officers to gather information on mosquito population at more locations.

The latest efforts are on top of the 50,000 Gravitraps already in place since 2017.

READ: Dengue cases on the rise: What you need to know to avoid mosquito bites

FINES AND REGULATION

In 2016, the Government amended the law to allow action against households found to be breeding mosquitoes, regardless of whether they are in active dengue clusters. The penalty is a S$200 fine.

As of March this year, more than 600 households have been fined for mosquito breeding. In addition, seven Stop Work Orders have been issued to construction sites found to have breeding spots. Three contractors have also been prosecuted in court for repeat offences.

In the first three months of this year, more than 200,000 inspections were conducted by the authorities, including about 1,800 carried out at construction sites. In total, 2,900 instances of mosquito breeding habitats were uncovered.

FOGGING

This method has its limitations: It is only effective if the chemicals come into direct contact with the mosquitoes.

In addition, fogging does not only kill mosquitoes, but also reduces the number of mosquito predators, such as dragonflies. While the method is still used, the NEA advises fogging to be carried out only when there is a mosquito nuisance problem or a disease outbreak.

(Photo: Reuters/Edgar Su)

VACCINES

In October 2016, a dengue vaccine, Dengvaxia, was approved for use for those aged 12 to 45.

However, health authorities later issued advisories on its use after its manufacturer released a report showing that Dengvaxia could worsen symptoms for those not previously infected with dengue.

The Ministry of Health (MOH) subsequently worked with medical laboratories in public healthcare institutions to make serological testing available to medical practitioners. Serology testing to identify previous dengue infection was made available at the major hospitals in Singapore.

To date, Dengvaxia remains a controversial vaccine. MOH does not provide subsidies or allow the use of Medisave for the vaccine as it “would not be a clinically and cost-effective means to tackling dengue infection in Singapore”.

Dengue vaccination is not part of the national immunisation programme. The vaccine is only given to individuals where the benefits outweigh the risk, instead of the population at large.

PUBLIC EDUCATION

Every year, a national dengue prevention campaign is usually launched in mid-May, ahead of the peak dengue season which runs from June to October.

This year, a spike in the number of dengue fever cases in the first three months had prompted the early roll-out of the campaign.

After this year’s campaign was launched on Apr, 81 divisions across Singapore had organised more than 440 dengue prevention events and activities.

Mayors, grassroots advisers, community leaders and dengue prevention volunteers visited residents to heighten public awareness and vigilance against mosquito breeding and dengue. They shared dengue prevention tips, including how to identify potential mosquito breeding habitats and reminded residents to practise the 5-step Mozzie Wipeout.