SINGAPORE: Walk into any hawker center in Singapore and one might come across one of six food ventures by Yu Kee Group including the eponymous Yu Kee Braised Duck Rice stall.

Apart from their famous duck rice, Yu Kee also owns food brands like Penang Kitchen, My Kampung Chicken Rice and Suka Ramai. It is also in the business of running food courts with its own two chains, halal-certified My Kampung Food Court and Kampung Food Court.

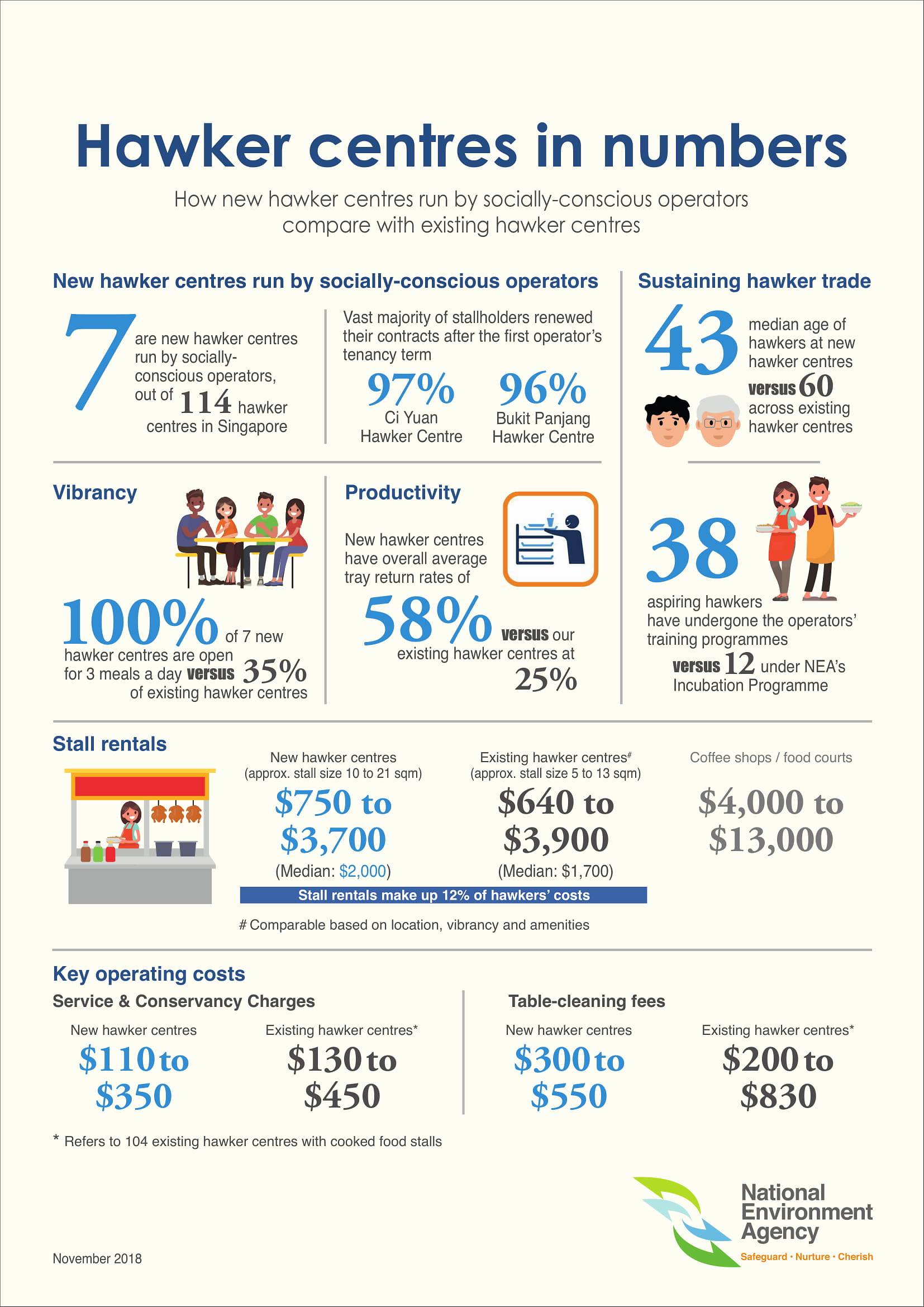

The group operates more than than 50 stalls, a quarter of which is located within hawker centres, including those run by social enterprises. These so-called socially-conscious hawker centres (SEHCs) were introduced in 2015 and have been in the spotlight recently as hawkers located within them grapple with the new model of hawker centre management.

The government said a review of this “generally sound” model is underway to allay hawkers’ concerns over low profit margins, rising operating costs and challenging operating conditions.

Yu Kee founder Seah Book Lock told Channel NewsAsia that the group has come a long way from its hawker beginnings in the 1950s as a street pushcart stall. While he acknowledged the challenging environment for hawkers today, he said they “can still succeed” as he did.

SEIZING THE OPPORTUNITY TO GROW

Mr Seah said Yu Kee started with a stall operated by his father at Lakeview Hawker Centre in the 1970s. In the 1990s, he and his four brothers expanded the business to eight stalls.

“Around the 1980s, I realised that there were a lot of new neighbourhood centres and coffeeshops spaces in Yishun. Rent was cheap at that time and business at these eateries was very good,” he said.

“People who moved from kampongs to these new flats had some money and they were willing to spend more on food unlike during my father’s day where people mostly ate at home,” Mr Seah added.

In the last decade, Yu Kee decided to set up a central kitchen which helped not only to maintain quality but also allowed them to scale up, he said.

However, just when the business was growing with the central kitchen, Yu Kee was hit badly by SARS in 2003 and two bouts of Avian flu in 2004 and 2006.

“We saw some brands which were selling chicken or duck dishes shutter their business and did not recover from that time,” said Mr Seah.

“After the second Avian flu outbreak, we were scared by how affected the business was and I decided that we had to venture beyond duck rice. We started with Suka Ramai which offered halal char kway teow,” he added. The new brands came about after research and development of new recipes.

Yu Kee Braised Duck Rice. (Photo: Fann Sim)

Like Mr Seah, former hawker Jimmy Soh seized an opportunity to start Tenderfresh in 1982, which offers fried chicken at an affordable price.

“Last time people rarely went to KFC. Only during birthdays or celebrations. At that time, nobody sold fried spring chicken at all. We were the only one,” Mr Soh said.

The business idea was sparked when he worked as a chicken salesman. He noticed that his customers were rejecting undersized chickens for larger ones. He decided to sell them as fried chickens as he did not want to let them go to waste.

In the first year at Whitley Road Hawker Centre, business was “really bad” and Mr Soh’s stall chalked up meagre sales – S$50 to S$60 daily.

“I was forced to add new products to the menu like barbecued chicken wings. That recipe was so good that before I opened my stall, orders would come in for say, 300 pieces of BBQ wings and spring chicken,” he said.

After a few years a second Tenderfresh outlet was opened at a coffee shop in Jurong.

“It’s not that we made money and so we wanted to expand. I had the thought that if we had one outlet, there is a limit to how much money we can make. So we decided for my wife to open a second outlet so we can make more. We had the dream to grow bigger,” he said.

Mr Soh said he wanted his brand to be seen everywhere and to become a household name so the company expanded rapidly and worked on its branding. For instance, the brand works with actor-host Ben Yeo who co-owns several outlets. From a hawker stall, Tenderfresh expanded first through coffeeshops but later moved onto having its own eateries such as its flagship store on Cheong Chin Nam Road and hawker-themed restaurant Hawkerman.

“We had an outlet in Clementi and that’s where the universities are. So we targeted students and came to be a student favourite,” Mr Soh said.

Tenderfresh now has 68 outlets across its food brands. It also has a presence in regional capital cities such as Kuala Lumpur and Yangon. At one point, it had more than 100 outlets but some had to shutter due to manpower shortages.

“At the end of the day, hawker work is very tough work. I have worked those hours and I know it myself. 14 to 16 hours a day with little breaks, it is not an attractive job,” Mr Soh said.

While operating conditions now may be different from when the two men started as hawkers, Mr Seah was optimistic that hawkers today can still succeed regardless of where their stalls are, SEHC or not.

What is important is the recipe, the hawker’s commitment to consistency and quality and good service, said Mr Seah. That is half the battle won, Mr Soh said.

DIFFICULT CONDITIONS TODAY, BUT STILL POSSIBLE TO SUCCEED

Mr Soh said that when Tenderfresh first started out at Whitley Road Hawker Centre in the 80s, monthly expenses including rent and miscellaneous charges were about S$230. Today, running a hawker stall can run one’s expenses up to S$3,000 to S$4,000, he said.

However, he was quick to point out that the environment then was different.

“There were not really these extra services like cleaning services and the area was quite dirty,” he said. There were also subsidies for first-generation hawkers who moved from the streets to newly-built hawker centre premises, he added.

How new hawker centres run by socially-conscious operators compare with existing hawker centres. (Infographic: NEA)

Apart from operational costs, raw material costs have gone up over the years and food prices do not commensurate the increases, he added.

“Over the years, these costs have increased by 40 to 50 per cent. The selling price has not increased 40 to 50 per cent. The selling price increased only about 20 to 30 per cent. In a way, they are earning less than first-generation hawkers,” he said.

Tenderfresh used to offer its fried spring chicken for S$3.50 in the 80s.

Today, it continues to offer the same signature fried chicken but at S$10.50. But the chickens used are now bigger and can be shared by two to three persons.

Despite that, rising costs have eroded profit margins to about 5 per cent, he said. But Tenderfresh makes up for it in its volume of sales and collaborations with other F&B brands, Mr Soh added.

READ: Profit margins for hawker fare? As low as 20 to 30 cents

In such an environment, he acknowledged that hawkers need a strong commitment to succeed, adding that other jobs would offer better perks such as annual leave entitlement, medical benefits and regular working hours.

“When the younger generation come out to work, they can look for a S$3,000 to S$4,000 job easily. When they come to join as a hawker, I doubt they can get S$3,000 to S$4,000. Some even can make S$1,000 to S$2,000 or even in worse cases, make losses. So do you think it’s worth for them to give the hawker trade a try?” said Mr Soh.

Mr Soh wondered if Tenderfresh would be as successful if it was to start and operate in the current environment.

READ: COMMENTARY: Our hawkers deserve more

SUPPORTING HAWKERS TODAY

To support the vocation, Mr Soh has partnered up with young hawkers by opening up his centralised kitchen to help them deal with rising costs while expanding their business.

Mr Soh said that in the last few years, Tenderfresh has worked with four second- and third-generation hawkers including Yong Tan, the son of “Hokkien Mee Master” Tan Kue Kim, to preserve his father’s legacy.

Tenderfresh founder Jimmy Soh continues to offer his signature fried spring chicken and grilled chicken wings, recipes he perfected from his hawker days. (Photo: Fann Sim)

Under the collaboration of more than a year, an area was carved out of Tenderfresh’s high-tech central kitchen to allow Warong Kim to scale up its food production with savings.

The brand expanded to set up two hawker stalls Warong Kim’s Goreng Delights at two SEHCs at Our Tampines Hub and Kampung Admiralty.

READ: Fish balls made by hand and sold out daily? Meet one of a rare breed of hawkers

“For them to start up themselves, it’s very costly. They have to put in S$300,000 to S$400,000 to start a central kitchen. You must also have at least 15 outlets then your central kitchen will make sense if not it will be a cost burden,” he said.

“It’s also a win-win situation. I can have more business, my volume will grow. What we can supply them is way much cheaper,” he added. The collaboration puts him in touch with F&B owners that could potentially complement the food offerings under Tenderfresh and diversify his business, he said.

In this way, Mr Soh said he can also extend a hand to help young hawkers and preserving disappearing traditional dishes.

“You can succeed. Have a good recipe. Aim for quality instead of quantity or extras like ‘Instagrammable food’ and so on. These things are no use,” he said.