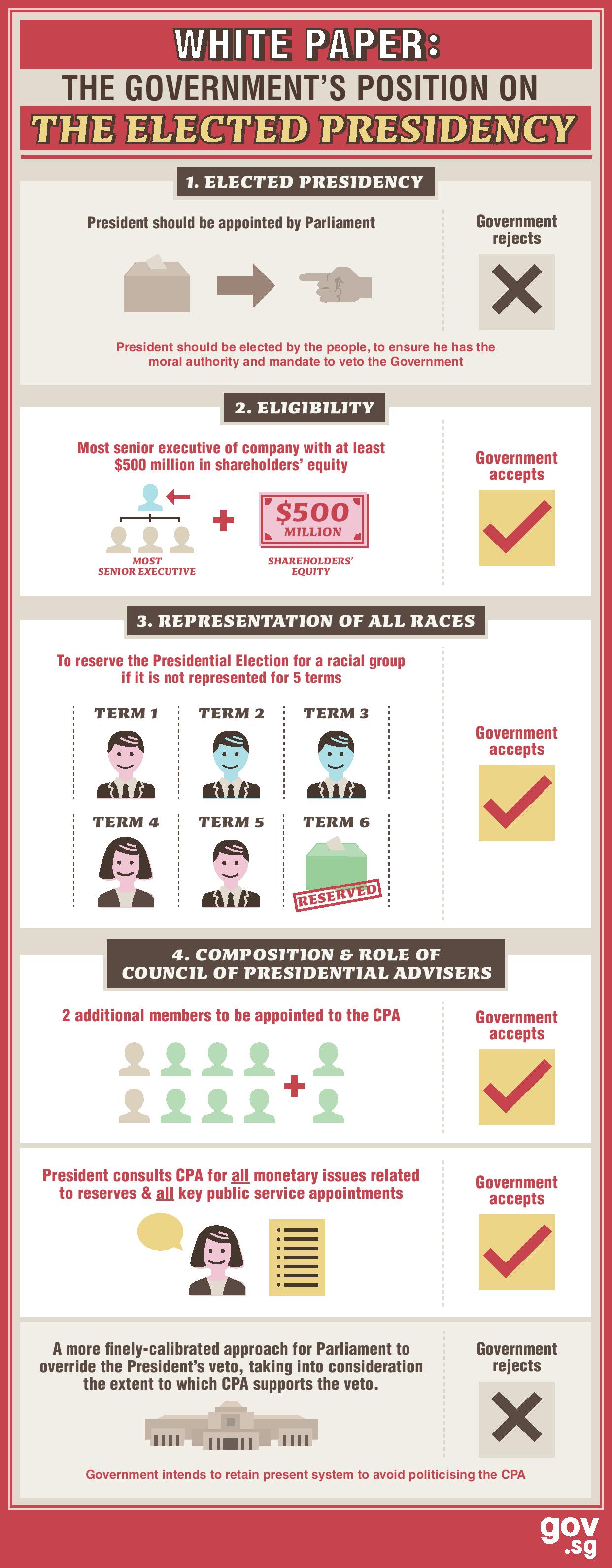

The Council of Presidential Advisers (CPA) will be given a stronger voice as the president will have to consult it on more issues and its size will be increased from six to eight members.

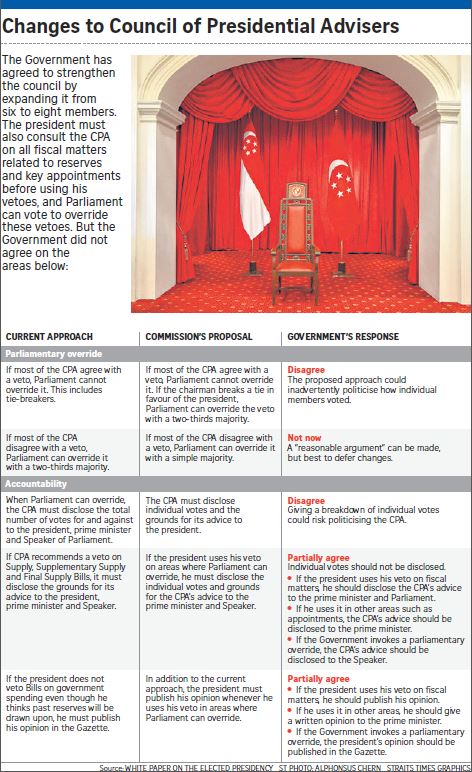

But the Government has rejected a proposal that the CPA’s degree of support for a president’s veto should affect how easy it is for Parliament to override the veto.

It set out its position on these recommendations of a Constitutional Commission in a White Paper released yesterday.

The commission’s proposals last week included some related to the president’s custodial powers. It suggested that in all fiscal matters relating to the national reserves and public service appointments, the president must consult the CPA before exercising his veto.

Currently, the president needs to do it only for some, not all, of these matters. The Government accepted the change.

It also gave the nod to the proposal that when the CPA disagrees with a presidential veto, Parliament should be able to override the veto on all such issues – not just some.

But it rejected another idea: that the stronger the CPA’s support for a veto, the harder it should be for Parliament to override it.

Currently, if a majority of CPA members agree with a presidential veto, Parliament cannot override it.

This includes cases where the chairman casts a tie-breaking vote. The panel proposed that in such tie- breakers, Parliament can override the veto with a two-thirds majority.

If a majority of CPA members disagree with a veto, Parliament should be able to override it more easily: with a simple majority, not the current two-thirds majority.

The Government said this “provides a more finely calibrated approach”, but still rejected the idea.

“The calibrated approach may unintentionally emphasise or even politicise how individual members of the council, particularly its chairman, have voted, instead of the collective judgment of the council as a whole,” it said.

As for letting Parliament override a veto with a simple majority if the CPA disagrees with the president, the Government said “a reasonable argument can be made” for this.

But as the law is being changed to allow parliamentary overrides on more issues, further changes on the required majority are best deferred to a future review, it added.

As the proposed changes will increase the CPA’s scope of work, the commission suggested expanding it from six to eight members.

The Government accepted this, as well as proposals to set guidelines in appointing members and make both new terms and reappointments last for six years.

On proposals to make the CPA’s decision-making more transparent, the Government agreed with some but not all the suggestions.

The proposals concerned when and what information has to be disclosed to the president, prime minister and Speaker of Parliament, and when the president’s opinion should be made public.

On whether the individual votes of CPA members should be made known, the Government said it prefers the current system of revealing only the total number for and against. Giving a breakdown of individual votes “could risk politicising the council, and consequently undermine its stature and independence”, it said.

As for conveying the council’s advice to the prime minister and Speaker, the Government agreed this should be done when the president is vetoing Supply Bills, Supplementary Supply Bills or Final Supply Bills – which are Bills related to government spending. In these situations, the president will also have to publish his opinion in the Gazette.

But for other veto areas – like key appointments – a balance must be struck between accountability and “protecting potentially sensitive and confidential information”, said the Government, setting out “a more calibrated approach to publication”.

What if the president neither assents to a Bill nor vetoes it?

Currently, he is deemed to have consented after 30 days have passed, in the case of certain Bills.

The commission suggested making such a deadline apply to all situations in which a parliamentary override can be invoked, and extending the wait period to six weeks.

The Government agreed and went further, applying a deadline to not just Bills but also the president’s powers in areas like detention orders under the Internal Security Act.

It decided to keep the 30-day deadline for time-sensitive matters like Supply Bills, and to shorten this to 15 days in “exceptional cases” on urgent matters, though it did not specify what these might be.

janiceh@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on September 16, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.