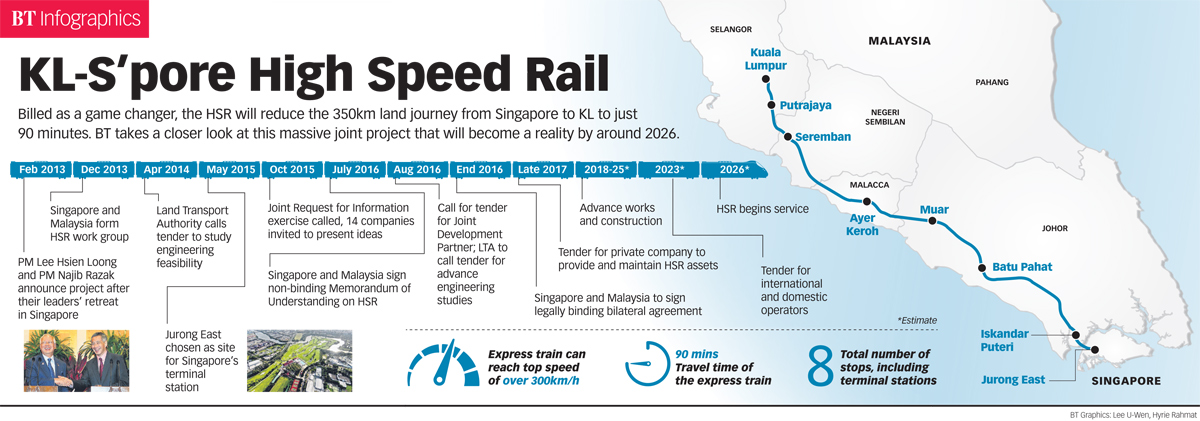

A planned high-speed rail (HSR) connecting two major Southeast Asian commercial hubs, Singapore and Kuala Lumpur, is a feather in the cap for regional economic integration but profitability and political manoeuvring may overshadow the ambitious project.

Officials last week signed a memorandum of understanding (MOU), the precursor to a legally-binding bilateral agreement at year-end, and an international tender will be called in August to appoint a joint development partner. So far, Japan has expressed interest in bidding, pointing to the spotless safety record and famed reliability of its Shinkasen bullet train, local media reported.

The HSR, due to start operations in 2026, is a big win for the Association of Southeast Asian Nations (ASEAN), which has been pushing for deeper regional integration.

The 10-member bloc launched the ASEAN Economic Community (AEC) initiative last year in a bid to unite Southeast Asia into a single market and production base, with a focus on free trade in goods and services, free flow of skilled labour and liberalized investment. But so far, progress has been tepid due to domestic political concerns.

Now, a recent report from Nanyang Technological University (NTU), has warned that the HSR could struggle to provide the hoped-for boost to ASEAN cohesion. HSR projects typically struggle for years before turning a profit, research fellow Wu Shang-su and associate professor Alan Chong noted in the report. For example, it took more than two decades for the Eurotunnel linking Britain and France to turn a profit, according to the NTU report.

“With operating deficits common among most HSR operators around the world, the Singapore-Kuala Lumpur HSR may not be an exception,” the report said. “Despite the possibility of bilateral commuting services theoretically becoming profitable, construction and maintenance costs would surely rely on overall income.”

Moreover, with commercial aviation as the railway’s primary competitor, redirecting large numbers of aerial passengers to the HSR may not be feasible.

There are about 45 daily flights between the two capitals, with average capacity of each flight at about 200 people, which meant 9,000 daily passengers could be carried in both directions at maximum, the report said. But one HSR train could seat a maximum of 1,000 passengers, according to news reports, so it would take 10 to 15 uninterrupted train services per day, assuming the HSR performs at peak capacity every time, to match the number of passengers flights could carry, the report continued.

Ticket pricing would also be a key issue, particularly if the HSR was meant to compete with cars, buses and conventional trains.

“If the HSR charges too much, passenger traffic would not significantly contribute to its finances, the NTU report said. “If the HSR tickets are priced too low for recouping its sunk costs, increased passenger volume may not adequately compensate but contribute to overall financial deterioration.”

Navigating through government bureaucracy could also derail progress.

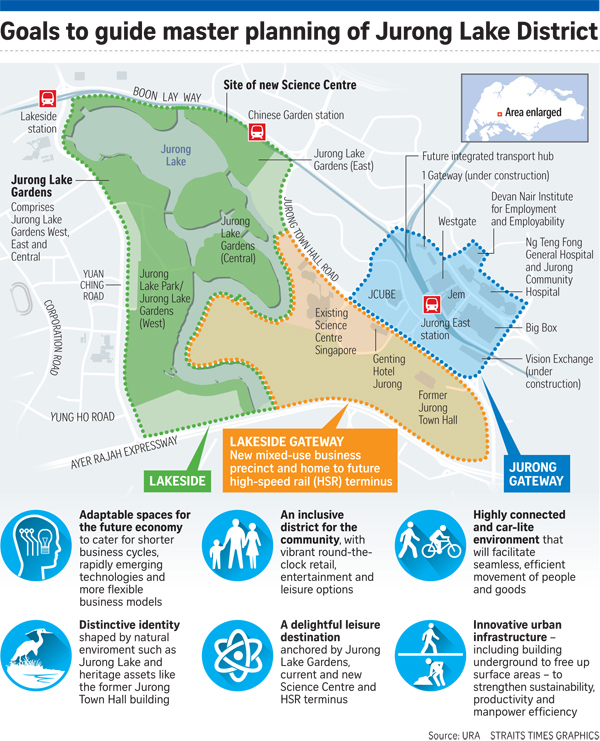

The report explained that HSR projects tended to be lucrative when supported by urban development such as airports, restaurants, cinemas and shopping outlets, near the new rail stations. But in Malaysia, undertaking such land development projects would require backing from both federal and state governments, which can be a complicated process, the report noted.

“Therefore, building HSR lines could require political bargains that may result in detours, or even impasse, in striking an agreement amongst various political forces.”