AFTER Cambodia’s most predictable election last month saw the ruling Cambodia People’s Party (CPP) claim a landslide victory, Prime Minister Hun Sen is now left with the tricky question of who will succeed him when the time comes.

After 33 years in power, and an unapologetic refusal to give it up, the 65-year-old Hun Sen resembles more of a dictator figure than a leader of a truly democratic state. Which leaves the question of succession.

This impression is only supported by the coordinated attack on his political opposition and disregard for press freedom in the build-up to the July 29 election, which saw the CPP win all 125 seats in parliament.

Hun Manet, son of Cambodian Prime Minister Hun Sen and leader of the Cambodian People’s Party (CPP), casts his ballot during the country’s sixth general election in Phnom Penh on July 29, 2018. Source: AFP/Tang Chhin Sothy

Like any self-respecting dictator, Hun Sen looks set to pass on the family business to one of his sons, most likely his eldest, Hun Manet.

While this understandably has fans of democracy concerned, Asia-Pacific is far from a stranger to the odd political dynasty. In fact, across the region, and Southeast Asia in particular, there have been many instances of good old-fashioned nepotism or kids hanging off the coattails of mum or dad.

Here are some of the recent examples of Southeast Asia’s high-powered family successions:

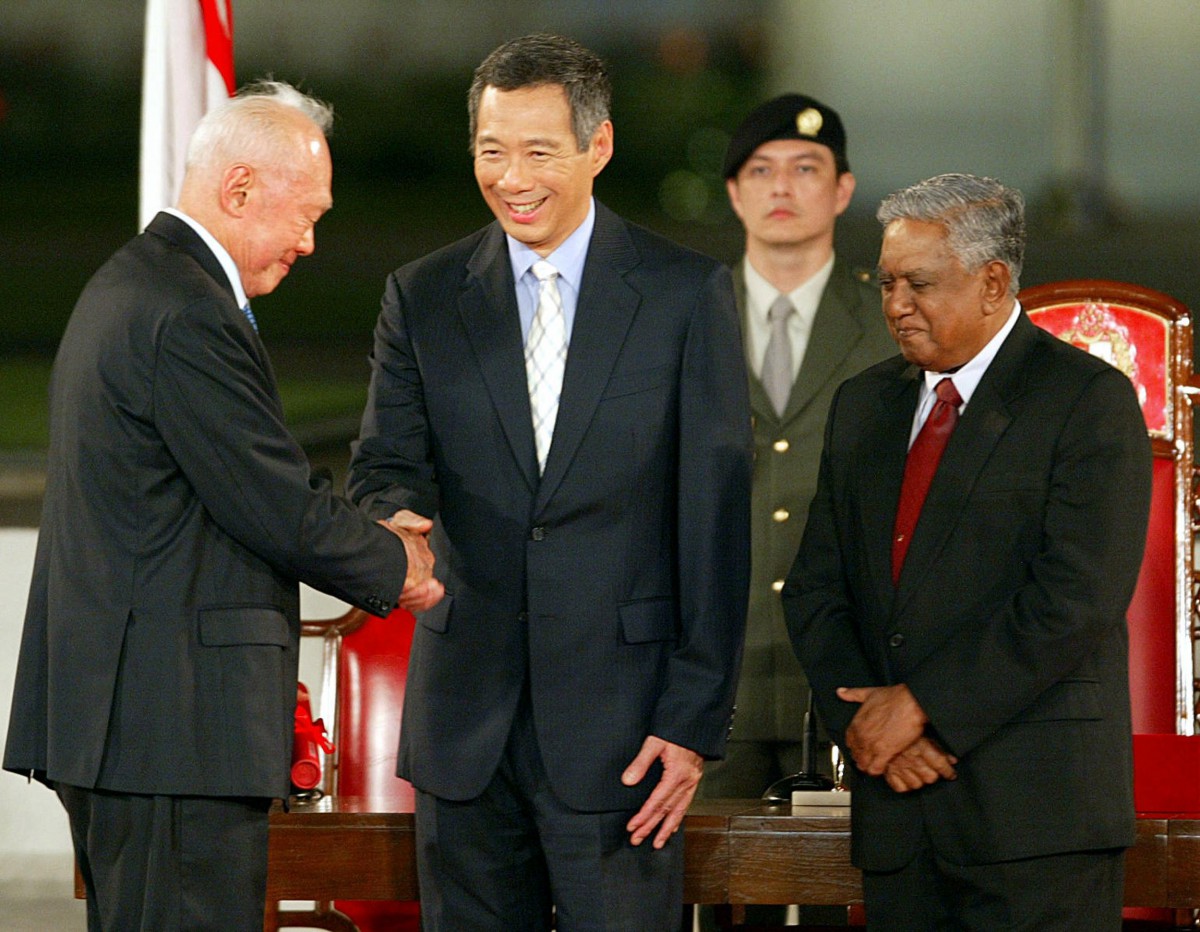

Singapore – Lee Hsien Loong

Singapore’s founding father Lee Kuan Yew congratulates his son, newly installed Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong (C) as President S.R. Nathan (R) looks on after the junior Lee took his oath of office at the Istana presidential palace in Singapore 12 August 2004. Source: Roslan Rahman/AFP

The legacy of founding father Lee Kuan Yew still lauds over Singapore, in more ways than one.

Still seen as a saviour who oversaw Singapore’s transition from third world to first world in a single generation, the power of association with Lee Kuan Yew is still a powerful one.

Five years after Lee senior left the office of prime minister, his eldest son, Lee Hsien Loong, took up the mantle, where he remains today.

Lee led his People’s Action Party to victory in the 2006, 2011 and 2015 general elections. But the reign looks set to end as Lee has set 2022 as the year he will retire and there is still no clear frontrunner when it comes to succession – unusual for Singaporeans who are accustomed to knowing well in advance who their next leader will be.

Malaysia – Najib Razak

Former Malaysian prime minister Najib Razak (C) arrives for a court appearance at the Duta court complex in Kuala Lumpur on July 4, 2018. Source: Mohd Rasfan/AFP

Malaysia’s newest former-PM has been hitting the headlines for all the wrong reasons recently. Standing trial for corruption after his long-ruling Umno lost out to the underdog opposition in a May election, the future looks far from bright for this former golden boy of Malaysian politics.

It’s hard to say what Najib’s father and Malaysia’s second ever prime minister, Abdul Razak, would make of his son’s predicament.

That’s not the only powerful link the Razaks have. Najib’s uncle, Hussein Onn, was also prime minister from 1976 to 1981.

Upon the death of his father in 1976, Najib was elected to take his father’s place in the lower house of parliament. From there, he worked his way up the ranks and was considered a rising star in the party, eventually making it to the top spot in 2009.

Things took a turn for the worse in 2015 when the embattled PM, shortly after implementing a hugely unpopular 6 percent goods and services tax, was then implicated in a corruption scandal involving 1Malaysia Development Berhad (1MDB), a Malaysian state-owned investment fund.

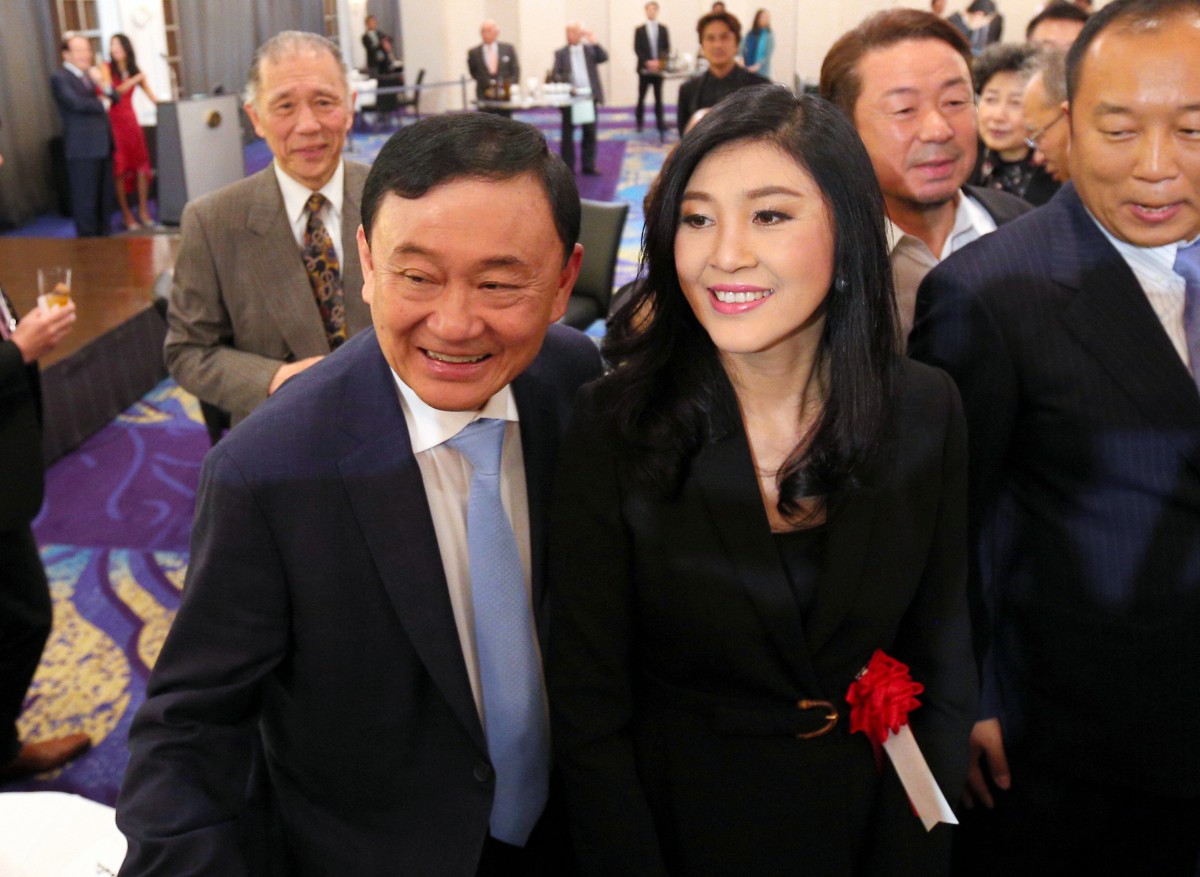

Thailand – Yingluck Shinawatra

Former Thai prime ministers Thaksin Shinawatra (L) and his sister Yingluck Shinawatra (R) smiling as they attend a social event in Tokyo. Source: Yasuhiro Sugimoto/Asahi Shimbun/AFP

The Shinawatra’s haven’t had a whole lot of luck in their later political careers, as both Yingluck and her brother Thaksin fell victim to military coups that ended each of their stints as prime minister.

Thaksin came first, being ousted from office in a bloodless military coup in 2006. He now lives in exile after being found guilty of corruption and sentenced to two years in prison.

He claims the charges were politically motivated and, despite living largely in Dubai and the UK, has maintained a strong following back home.

As head of the Phak Puea Thai – or Thais Party – Thaksin’s younger sister, Yingluck, took office in 2011. She lasted just three years before being dismissed from office for illegally removing a government official early in her term.

Just days later, another coup resulted in a new ruling council and Yingluck found herself slapped with corruption charges stemming from a rice-subsidy programme instituted by her government. She has since been convicted and the ruling military junta is calling for her return to Thailand to serve her sentence.

The pair likely got their taste for the tumultuous world of politics from their father who was a member of parliament from the late 1960s to the mid-1970s.

Burma – Aung San Suu Kyi

Myanmar’s State Counsellor Aung San Suu Kyi inspects an honour guard during an official welcoming ceremony at Parliament House in Canberra, Australia, March 19, 2018. Source: AAP/Mick Tsikas/via Reuters

The shoes of national hero Aung San are pretty big ones to fill. But his daughter Aung San Suu Kyi has done a fine job of doing just that and making a controversial name for herself along the way.

The Burmese nationalist leader was instrumental in securing Burma’s independence from Great Britain.

He was assassinated in 1947 by a political opponent, securing his status as a beloved national hero; an image that still prevails today.

Aung San Suu Kyi embodied her father’s freedom fighting ways, speaking out against the brutal and bloody rule of military strongman U Ne Win. Her non-violent struggle for democracy in Burma led to her arrest in 1989. She was placed under house arrest and left completely cut-off from the outside world.

She was offered her freedom if she agreed to leave Burma on her release. She refused.

Her staunch crusade for human rights landed her the Nobel Peace Prize in 1991.

She was released in 1995, only to be sentenced once again in 2000 and 2003 for breaking the tight restrictions placed on her by the military government.

Her incarceration became a rallying cry for the international community and the attention she received became a thorn in the side of the Burmese repressive regime.

Eventually, in 2015, the poster child for democratic freedom led her National League for Democracy party to victory in what was the country’s first openly contested parliamentary election.

Since then, Suu Kyi has retained her image as the darling of the people at home but has had her human rights credentials questioned internationally following her refusal to denounce the military crackdown on Rohingya Muslims in Rakhine State.