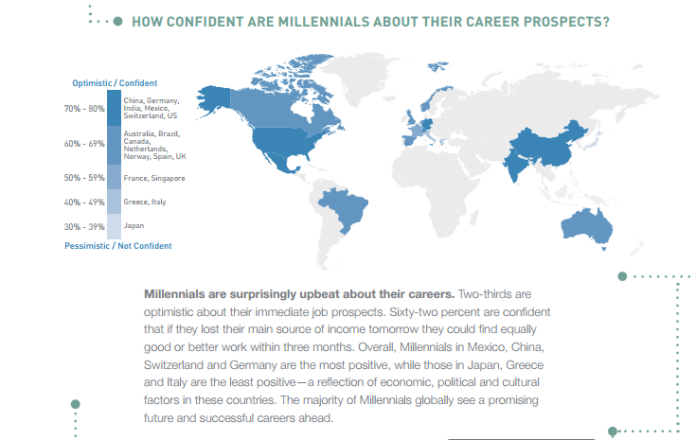

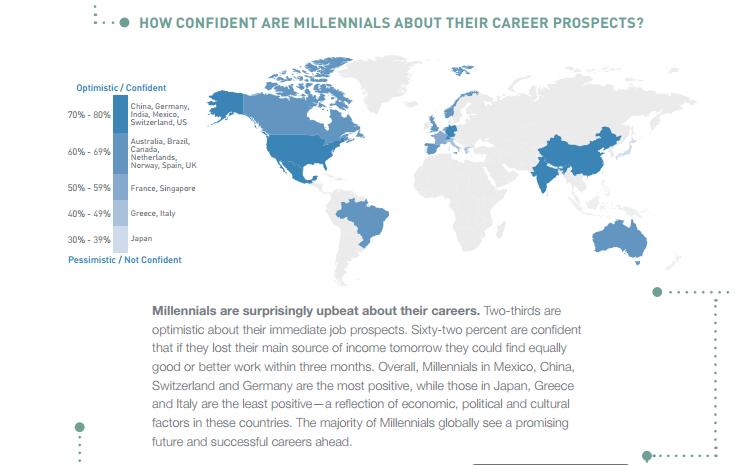

TOKYO/SINGAPORE — Singapore millennials are among the world’s most gloomiest millennials, coming in only behind Japan, Greece and Italy, according to a survey by the ManpowerGroup.

Around half of Singapore millennials surveyed felt pessimistic about their immediate career prospects — they were not confident that if they lost their main source of income tomorrow, they could find equally good or better work within three months.

In comparison, at least six in 10 millenials in countries such as China, Mexico, Australia, Norway and India, were confident of their career prospects. The most pessimistic group were from Japan, where fewer than four in 10 millenials saw bright futures and successful careers ahead. The Japanese are even more downbeat than young Greeks, who have suffered Great Depression-like conditions and political upheaval in recent years.

The survey also found that 14 per cent of Singapore millennials believed they would have to work until the day they die, compared to 12 per cent globally. Singapore is joint-fourth on this list, behind Japan (37 per cent), China (18 per cent) and Greece (15 per cent).

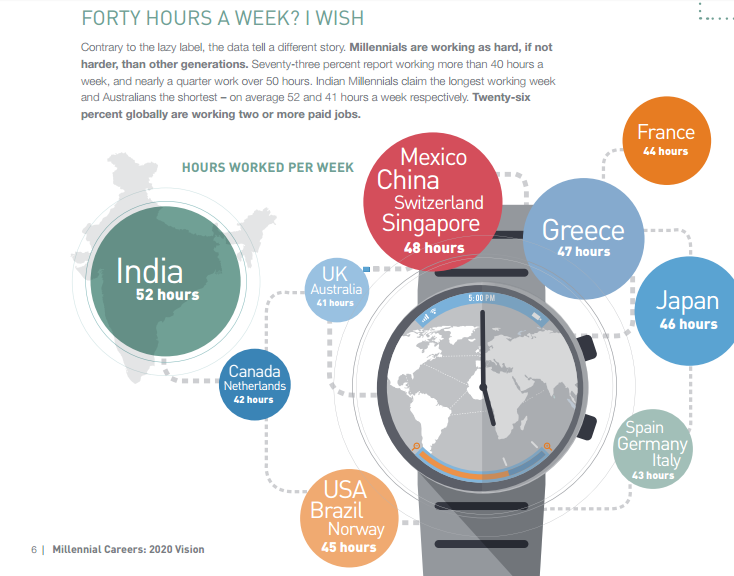

Meanwhile, Singapore millennials work more hours in a week than even the Japanese, according to the survey findings. On average, Singapore millennials worked 48 hours a week, coming in second alongside Mexico, China and Switzerland. India millennials topped this list by working an average of 50 hours a week, while the Japanese worked 46 hours.

In total, about 19,000 millennials were surveyed across 25 countries, including 8,000 ManpowerGroup associate employees and more than 1,500 of of the company’s hiring managers.

WORLD’s GLOOMIEST MILLENNIALS

The ManpowerGroup survey shows definitively that millennials in Japan are the least optimistic about their career prospects and a significantly higher proportion believe they will work until they die.

In Japan, millennials face a future of paying to care for one of the world’s most rapidly growing elderly populations, with more than a third of them likely headed for a series of lower-paying dead-end jobs on the less desirable side of the nation’s dual labour market. Then there’s a public debt burden that ranks among the world’s biggest.

Sceptical that the nation’s pension system will be around to take care of them, 20-somethings are already concerned about life after retirement and scrimping to save for the future. Low and stagnant pay is forcing many to delay or even forgo marriage, home-buying and child-rearing.

Public debt may prove the biggest economic burden for them.

The share of the debt for each Japanese child under 15 stood at US$794,000 (S$1.1 million) each as of 2011 — more than two and a half times that of children in Italy and Greece, the two next-worst cases, according to Bertelsmann Stiftung, a German non-profit foundation. Because of that, and a disproportionately large share of social spending going to the elderly, Japan ranks as the world’s second-most “intergenerationally unjust” country, it said.

Young Japanese are responding in ways that are dragging on the economy. At a time when domestic consumption has stalled, their savings rate is on the rise, with those 25-34 years old saving a larger share of their earnings than any other age group in 2015, UBS said in a recent report, citing government data.

In fact, most of what little growth in consumption Japan has seen over the past decade has been driven by seniors, offsetting a decline among younger people, UBS said.

The OECD’s Jones notes that just to stabilise the debt at current levels would require difficult choices, likely including raising the sales tax from the current 8 per cent, which sits well below the OECD average of about 20 per cent, he said. The bulk of that will fall on the younger people who will be around longer.

“So if you’re a working-age person, you can see that there are heavy burdens coming,” he said. AGENCIES