Words by Mayo Martin / Multimedia by Lam Shushan

Read Part 1 of this series: Watching a way of life vanish

RIAU ISLANDS, Indonesia: The harbour at Belakang Padang island is a fluttering forest of colourful sails, in various shades of orange, red, blue and yellow, with a pier jam-packed with cheerful spectators come to see the action. It mirrors the high spirits of our host, Mazlan Mohd Nasir.

“Welcome to the Olympics – in Riau, not Rio!” the 54-year-old Singaporean quips.

The day is August 17 – Indonesia’s National Day – and we’re about to watch the first of a series of regattas that take place every year in the Riau Islands. It’s the modern-day incarnation of kolek racing, a tradition in the Riau-Singapore-Johor region since the 1800s when these fast, shallow crafts with enormous sails requiring dexterous sailors were common.

From the harbour, the skyline of Singapore’s Central Business District is visible a mere 15 kilometres away, but it might as well be a different world. Today, the Lion City is a busy port and its shorelines festooned with container ships – but 40 years ago, such kolek regattas would have been common along the coast.

Singapore’s development came with a price: The space to race these graceful, powerful and demanding sailboats that had been a way of life for nearly two centuries.

But here in the Riau Islands, after a period of also fading away, the kolek races have found their way back to popularity. Thanks, in part, to people like Mazlan.

Today, the reason for his good cheer is his family’s Pujangga – a craft with a bright yellow sail and bright orange stripe on the side which is racing.

It’s not the same Pujangga that Mazlan, as a stripling growing up on Lazarus Island in the 1960s, watched compete around the Southern Islands – and which he discovered languishing on Keban in the Riau islands in 1987.

No, it’s a new-generation version, built in 1997. Mazlan has spent many weekends shuttling from Singapore to Keban to supervise its sea trials and to train the nine-men crew tasked with steering Pujangga to victory.

But, we soon find out, simply finishing a race is easier said than done. Barely minutes after the siren to start the race goes off, Mazlan’s kolek capsizes.

Watch: The stomach-twisting moment when things go wrong, in 54 seconds

As the dejected-looking sailors limp back to the dock post-race, the reason is confirmed: Water seeped in, which can happen easily with a shallow boat like the kolek.

While packs of cigarettes are given out to the crew as consolation, we turn to Mazlan to see if he’s disappointed. “There’s another race tomorrow,” he shrugs, as we head to his home-away-from-home in Keban to recharge.

THIS IS RETIREMENT

More than an hour’s ride south from Belakang Padang, past speeding boats, the occasional fishpen, uninhabited mangrove islets and villages on stilts, lies Keban island.

Roughly a quarter the size of Sentosa – a mere kilometre from end to end – it is home to about 200 residents, mostly fishermen. The shoreline is dotted with wooden houses on stilts, and Mazlan’s family compound is one of the rare concrete ones.

As we dock and clamber up a rickety, makeshift jetty, his father welcomes us. A Singapore passport holder, 76-year-old Haji Mohd Nasir Awang, regularly travels back to the city-state, but most of the time he’s here on the island.

Like many of his generation from this part of the Riau Islands, as a boy Cik Nasir was sent to study in Singapore. He served in the pioneer civil service as a teacher and raised his family there, but once he retired, he moved back to the islands where his father and grandfather had served as penghulus.

While not a village headman like them, Cik Nasir is a respected figure in Keban. “I’ve got seven children, 25 grandchildren, and three great-grandchildren. They’re all living in Singapore, but they all spend their holidays here,” says Cik Nasir, who still has the straight posture and build of a sturdy islander, like his son. “And they’re all happy I’m here.”

Aside from Mazlan, also visiting today are his sister Lela, his nephew Firhan (a commercial diver) and two inquisitive younger nephews. Like Mazlan, they also regard Keban as their second home, a getaway from the intense pace of Singapore.

The place lacks some creature comforts (no electricity during the day, a practically non-existent cellphone signal). But on clear nights, Firhan tells us, the sky littered with stars is a sight to behold. A short boat ride away is Sugi island, where the marshes are lit up by countless fireflies.

And then there’s the view from the family verandah.

Entertainment is improvised – two small mirror balls hang attached to the ceiling fan in the living room. Shine a light on them, switch on the fan, turn up the music, and voila – you get instant discotheque, kampong-style, Lela says laughing.

BUILDING A KOLEK HUB

Inside the main house of the family compound is a special “altar” of sorts to their kolek exploits. Trophies and certificates are placed together with photographs of Mazlan’s grandmother and grandfather, who owned and raced kolek. A photo of the new Pujangga hangs over these.

Cik Nasir, who helps Mazlan supervise their kolek team, keeps an eye on the family’s long-term project in Keban – the construction of a chalet, which they hope will be a place for visitors to stay to learn more about koleks, and maybe even help boost the island’s economy.

It’s part of their long-term plan to create a kind of “kolek hub” in Keban involving the kampung folk.

But Mazlan is aware that they need to get the islanders onboard, which is why they’re taking it slowly. “We don’t want to rush because we don’t want to disturb the environment. We don’t want to shake up the place. It’s not a money-making venture; I look at building up the whole community,” he says.

Watch: How koleks are still made by hand, on Pulau Tjombol (1:43min)

While Mazlan admits that more needs to be done to pass on the knowledge of boat culture to the younger generation in Keban, he is encouraged by the growing interest in kolek racing. “I can see the enthusiasm is now really there. When there is a race, they really prepare for it.”

And of course, at some point, he hopes the enthusiasm can spread all the way to Singapore, too.

“I would love if Singapore had a team, then they participate (in the races). They can even build a kolek, leave it here (in Keban), so whenever there is a race, sailors can come and hop in.

“They can come and do sea trials, train and mix with the sailors down here. We can do a one-time race in Keban, then maybe it will start to grow,” Mazlan enthuses.

But, he adds: “Singapore is not an easy place to do a race anymore. There’s no open sea, and where are the spectators going to watch?”

YOUR PASSPORTS, PLEASE

Kolek racing in the Riau islands has seen a revival over the last two decades and more. But in Singapore, once many kampung sailors were resettled into flats in the 1970s and the sport lost headway, it never really caught on in a big way again.

The kolek eventually disappeared.

And even if a race were to be organised in Singapore inviting kolek sailors from Johor or the Riau Islands, it had become quite a hassle. Says Mazlan: “Because of security issues, immigration processes, it became very restricted and (you) couldn’t organise very freely.”

Historically, the waters between Singapore and the Riau islands have been a tricky place ever since the British and the Dutch decided to split up these territories between them in 1824. But that didn’t stop small boats from island-hopping, which was why you once had koleks from the Riau Islands competing in Singapore.

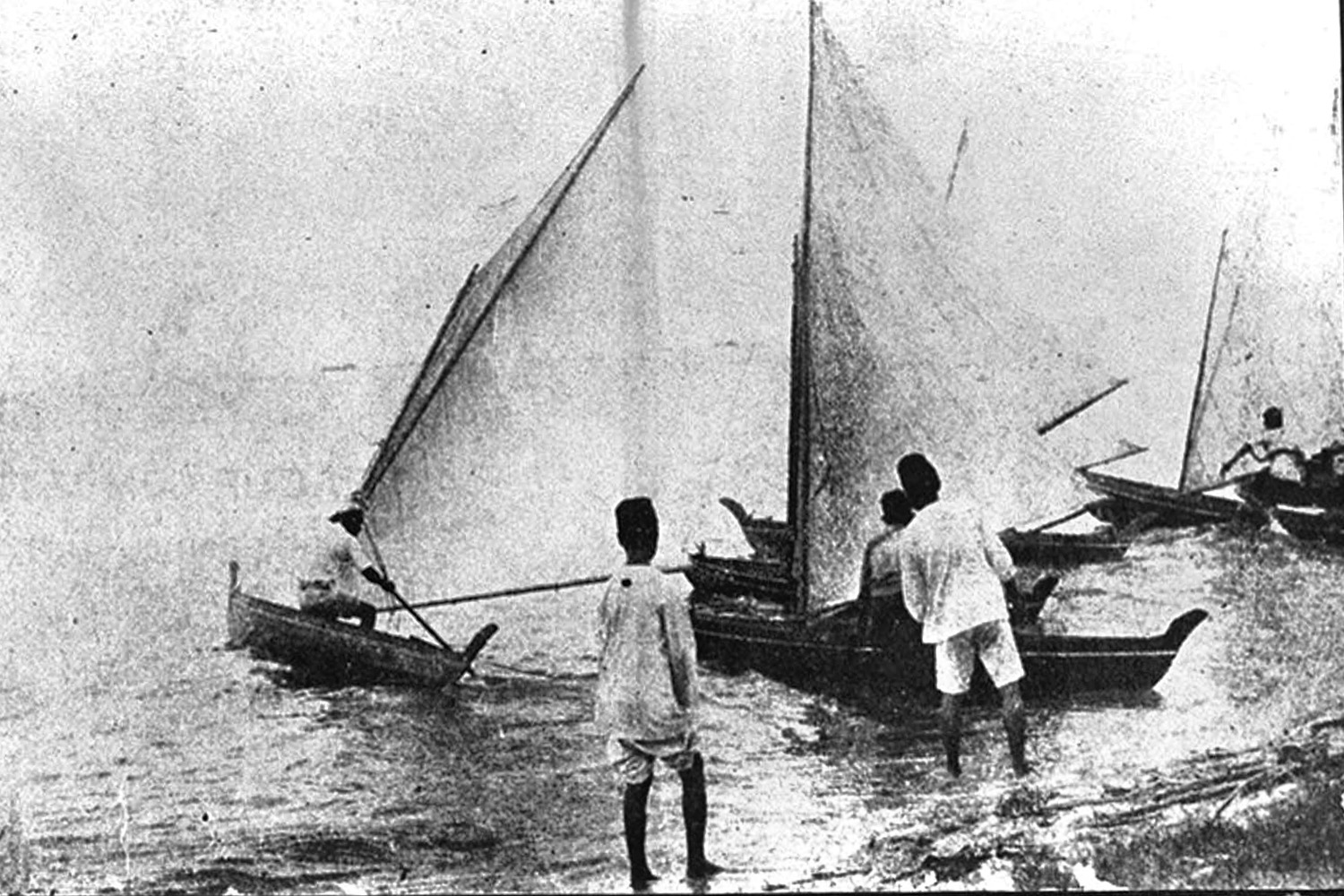

Kolek races held on Singapore’s beaches in 1928. (Photo: Sport Singapore)

However, once Singapore became a nation-state in 1965 and the Riau Islands formally became part of Indonesia, invisible boundaries were drawn on once-open waters, and things got more complicated. On a practical side, immigration rules made it harder and more expensive for Indonesian kolek to simply make a beeline for Singapore.

The last recorded race in Singapore was held at Sentosa’s Siloso Beach in 2001. Mazlan’s Keban crew had actually been among the Indonesian participants. He says his father had to pay for the passports of all the 27 sailors for the three boats they entered; each one cost S$300.

“It’s not like a European type of event where teams have the financial strength and sponsors – these are people from the kampungs and they don’t have such funds,” he explains.

THE ‘RIAU OLYMPICS’, PART 2

So while Singaporeans today are oblivious to the annual races happening just kilometres away, Riau islanders continue to race on.

It’s back to the ‘Riau Olympics’ and we’re there on Day 2 of the races, held in Pulau Buluh, an island just across from one of Batam’s huge shipyards.

On the way there, we pass by toy-sized unmanned boats called jongs racing in open water. These smaller versions of the kolek are popular among both the young and the old.

Just like in Belakang Padang, the atmosphere at Pulau Buluh is electric. The stilt houses facing the sea are packed with people. More are coming in, literally by the boatload, and parking their vessels where there’s space.

And just like at yesterday’s race, the racing boats make for an awesome sight. They’re all bunched together at the “starting line”, their colourful sails slightly tilted forward as if straining to be let loose.

Watch: The atmosphere at the kolek festival, in 1 min

It’s during times like this that Mazlan feels alive. Even though he no longer sails himself, but manages the team, the excitement is still there. “If there’s a race that I can’t attend, I start to feel uneasy to find out what the result is. It’s something that is very, very deep inside (me),” he says.

It’s a feeling that, unfortunately, his wife and two adult children don’t share. They’re back at home in the family’s Pasir Ris flat. When asked what they think about his kolek activities, Mazlan laughs: “They don’t like it! They think I’m wasting time or money, but I tell them this is my passion, so it’s okay.”

And then we hear shouts in the distance. The boats are off.

Read Part 1 of this story here. In Part 3 tomorrow: How they feast in Keban – and social media lends support.

Watch the CNA Insider short film (7:45 mins):