After living in Shanghai for nine years, Mr Teng Yiye, 38, and his family moved to a small town in neighbouring Jiangsu province in late 2014. It takes Mr Teng about an hour to drive to Shanghai to attend meetings for his interior design business, but he believes he made the right decision to leave the city.

In Shanghai, home was a 40 sq m apartment, valued at 1.2 million yuan (S$253,000). His daughter could not get into a public kindergarten as she did not have a local household registration, or hukou, which is needed to enjoy public services.

After moving to Huaqiao, a small town in Kunshan city, the family now lives in a spacious 160 sq m apartment that costs 1.1 million yuan. Better still, Mr Teng’s five- year-old daughter now attends a public kindergarten near their home as the local government is welcoming of migrants. He is from central Anhui province. “It’s more troublesome for me but, overall, the pros outweigh the cons. The cost of living is lower and the quality of life is better here as there are more open spaces than in Shanghai for my girl,” he told The Sunday Times.

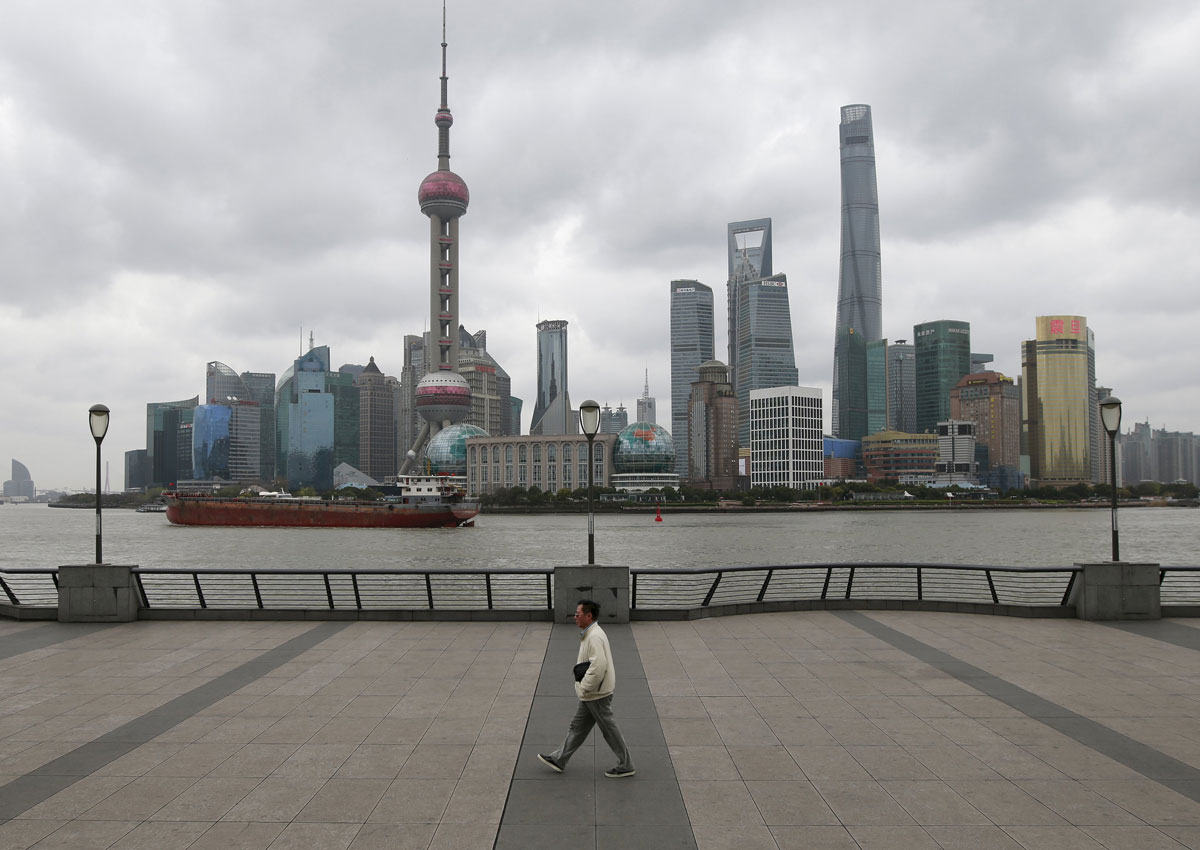

For decades, the financial hub’s cosmopolitan lifestyle and, more importantly, the job and business opportunities it offers have attracted migrants from all over China.

Last year, for the first time in 15 years, Shanghai saw a 1.5 per cent dip in the number of migrants to 9.81 million from 9.96 million at end-2014, according to figures released this month. This in turn led to a 0.4 per cent decline in its population to 24.15 million last year – the first decrease since China’s opening up and reform in the late 1970s.

The trend is attributed in part to the national phenomenon of migrants leaving coastal cities to return to inland provinces where opportunities are opening up, and also to the shrinking migrant population due to China’s low birth rates.

Shanghai officials have also cited reasons such as the city’s industrial restructuring efforts that phased out low-end firms and their workers, and demolition of illegal buildings that had housed migrants.

These are part of Shanghai’s efforts to support the central government’s urbanisation push, which is premised on making big cities more liveable with more sustainable population sizes. Shanghai has set a population cap of 24.8 million, which means migrant numbers can be expected to slow, if not decline.

But experts say Shanghai’s rising costs of living – especially property prices – and slow-climbing wages are also key factors pushing migrants like Mr Teng to seek a better life elsewhere. For instance, property prices in Shanghai jumped nearly 10 times in the 2000-2015 period while average wages went up almost three times from 2,033 yuan in 2004 to 5,451 yuan in 2014.

Feeling the squeeze is Ms Xie Xiaowei, 26, who is considering returning to Xiamen in Fujian province in the next one to two years. She moved to Shanghai in October 2014 to become a finance manager at an IT multinational corporation.

“I’ve been told that my rent, which already accounts for 30 per cent of my salary, will spike by 20-40 per cent. But my firm has announced a pay freeze this year and there’s no way young people like me can afford a decent-sized apartment in Shanghai,” she told The Sunday Times. Though she will have to take a pay cut of 20 to 30 per cent for a similar job in Xiamen, she believes it will even out as she has a property there and the cost of living is lower.

Even those who have just arrived in Shanghai say they can understand why the city is losing its allure.

Ms Sheng Qingwen, 25, a freelance website developer, moved to Shanghai last October to be closer to her clients in the neighbouring Suzhou and Shaoxing cities. But the Beijing native, who studied and worked in the United States for six years, said the quality of service at her apartment is lower than what she had experienced in Chicago and New York. “I’m giving myself another two to three years because there are more opportunities here. By then, hopefully other cities would have developed well and provide alternatives for me.”

For similar reasons, other big cities such as Beijing are set to see declining migrant numbers. For instance, the number of non-locals in Beijing rose by 39,000, or 0.5 per cent, to 8.22 million in 2015, the smallest increase since 1999.

Mr Song Yaoli, 43, who has worked in the capital for five years, plans to return to his home town Xi’an in northern Shaanxi within two years though it means taking possibly a 20 per cent pay cut. His wife and 13-year-old daughter have remained in Xi’an and he visits them at least once a fortnight. “The trade-off is narrowing as the standard of living and job opportunities in Xi’an are improving while Beijing has become too crowded,” said Mr Song, who is in software sales. .

Fudan University’s Population Studies Centre head Wang Guixin thinks the authorities should be concerned about the declining migrant numbers because they could have a negative impact on the big cities and the national economy.

A big city whose growth is impeded by a declining migrant pool would not be able to support its satellite cities, he said.

Also, Professor Wang noted that most migrants leaving the big cities are low-income workers like cleaners and couriers. A smaller migrant pool might lead to higher labour costs and product prices. “Just look at the inconveniences experienced by locals in big cities when migrants return home during the Chinese New Year,” he said. “Now think of it as a year- long phenomenon.”

kianbeng@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on March 27, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.