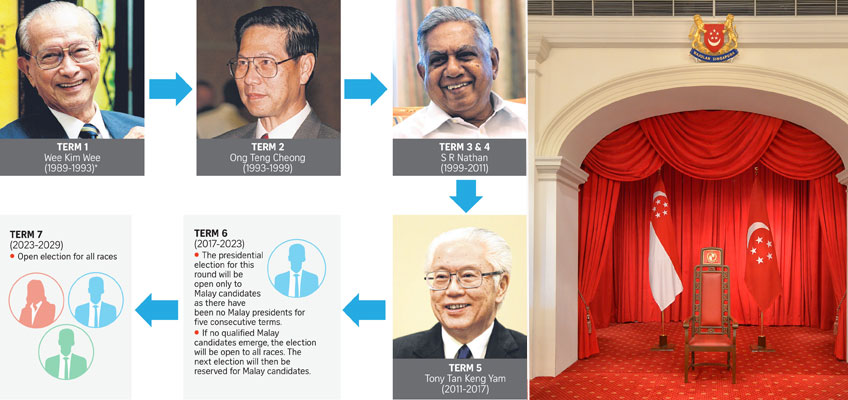

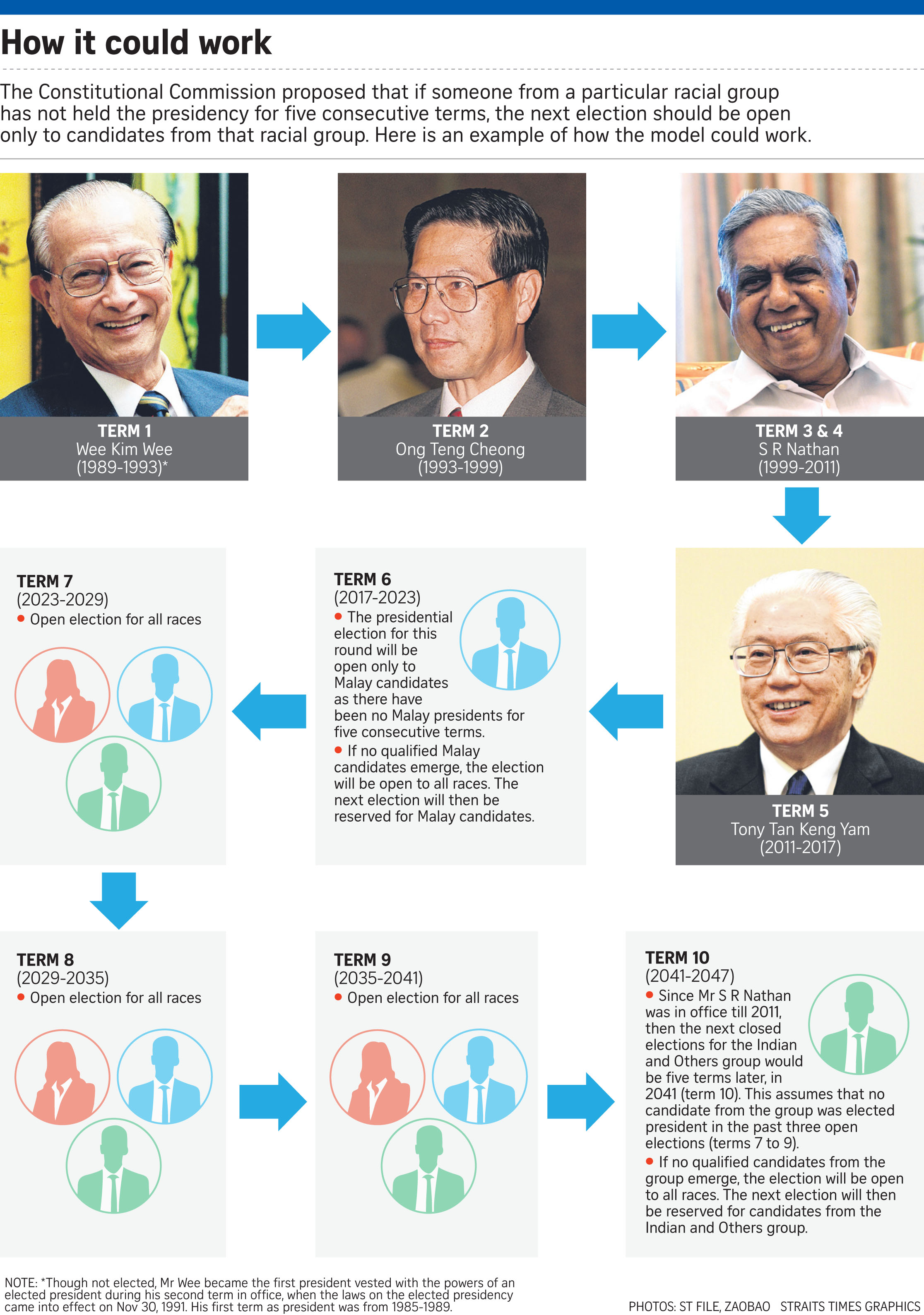

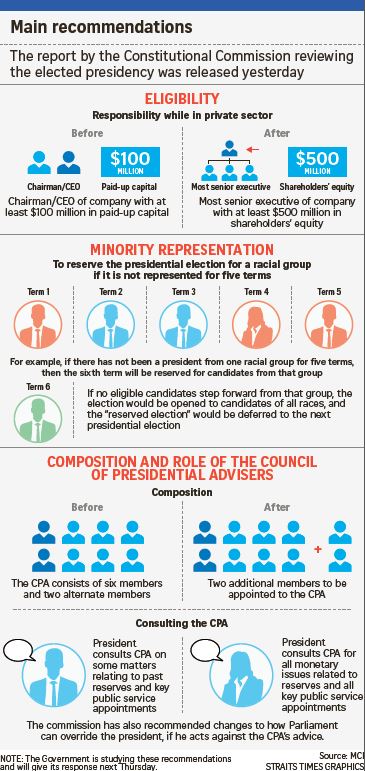

If Singapore has not had a president from a particular racial group for five continuous terms, the next presidential election should be reserved for candidates from that group, a high-level panel tasked to review the elected presidency proposed.

This ensures that the highest office in the land can be held periodically by someone from a minority community, which is crucial as the president symbolises the nation and should reflect its multiracialism, said the Constitutional Commission.

But it made clear that the eligibility criteria for candidates must not be lowered for anyone from particular racial groups to qualify.

The recommendation addresses a much-debated aspect which the commission was asked to look at by Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong: whether there should be a special provision in the law to ensure that Singapore has minority presidents from time to time.

The commission, chaired by Chief Justice Sundaresh Menon, concluded that it is necessary as Singapore is still working towards the ideal of being race-blind, but is not there yet.

In the meantime, there is a pressing need to ensure that no racial group is shut out of the presidency, said the commission.

The country has not had a Malay president since Singapore’s first president Yusof Ishak held the post from 1965 to 1970. Before independence, he had been Yang di-Pertuan Negara of the State of Singapore, the precursor to the presidency, from 1959 until 1965.

Read also: 4 things you need to know about the elected-presidency report

In its report to PM Lee, the commission said it is vital that minority candidates do not see the presidency as unattainable. So there are “strong justifications” for introducing safeguards that make sure the office “is not only accessible, but is seen to be accessible, to persons from all the major racial communities in Singapore”, it added.

To achieve this, it proposed a safeguard that kicks in only when there has been no president from any racial group for five terms, which works out to 30 years.

But if no qualified candidate of the particular race emerges, then that election will be opened to candidates of all races. The subsequent election will then be reserved again for candidates of the particular race.

Asked about this proposal, Law Minister K. Shanmugam said the Government is asking the Attorney-General (A-G) for advice on aspects of the commission’s recommendations to ensure representation of all the major races in the office of the president.

“The Government will announce its position once the A-G has given his advice and the Government has considered it,” he said.

The commission, in recommending the model, said it is the least intrusive way of ensuring minority representation.

For one thing, the provision is race-neutral and does not single out any one racial group for protection. It also has a “natural sunset” as it may never be triggered if presidents from various racial groups are elected during open elections.

Said the commission: “It enables the representation of all racial groups in the presidency in a meaningful way while being minimally prescriptive.”

There is also no danger of undermining meritocracy, as long as candidates are held to the same stringent qualifying standards for all elections, it added.

This was an area of concern raised during the commission’s hearings in April and May, by some groups and individuals who felt that reserving elections for particular racial groups would result in a president being elected by virtue of his race and not his abilities.

Some others had been against having a special provision, saying it may lead to calls for similar safeguards for other public offices.

But this argument, the commission said, failed to recognise the unique symbolic function that the president plays. “No other public office – not that of the prime minister, the chief justice or the Speaker of Parliament – is intended to be a personification of the state and a symbol of the nation’s unity in the way that the presidency is.”

The commission also said that “placing undue focus on the custodial role, to the exclusion of the symbolic, would oversimplify what is in truth a multifaceted institution”.

While a key role of the president, after the elected presidency was introduced in 1991, is to safeguard Singapore’s reserves, this did not diminish the office’s symbolic role.

Former prime minister Lee Kuan Yew, in a 1999 interview with The Straits Times, said that “the convention of rotating the presidency among the races was important to remind Singaporeans that their country was multiracial”, the commission pointed out. After Mr Yusof, Singapore’s next presidents were Dr Benjamin Sheares, a Eurasian, then Mr Devan Nair, an Indian, followed by Mr Wee Kim Wee, a Chinese.

The elected presidency came into effect in 1991, and Mr Ong Teng Cheong, a Chinese, was the first Singapore president to be elected at the polls. He was followed by Mr S R Nathan, an Indian, who served for two terms, and current President Tony Tan Keng Yam, a Chinese.

Said the commission: “It is because of the crucial symbolic role performed by the president that the office should periodically be held by persons from minority races.”

This article was first published on Sep 08, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.