In a fit of anger, the boss of Mr S R Nathan ordered him to sack an officer who had made a mistake.

But Mr Nathan, a mid-level civil servant then, moved the man to a corner table in the office instead, out of the sight of his infuriated boss.

Days later, his boss saw the man, called Mr Nathan and told him: “I would have been aghast if you had gone ahead and fired him. You did the right thing.”

That was in the 1970s.

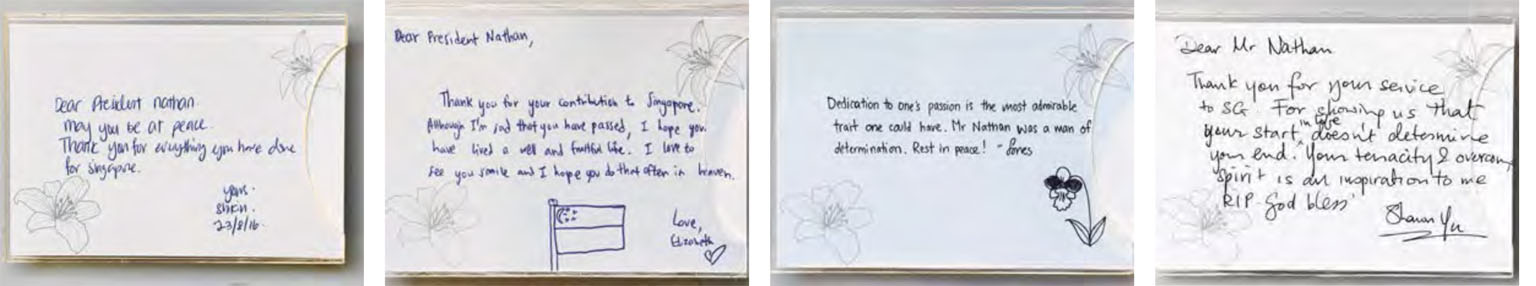

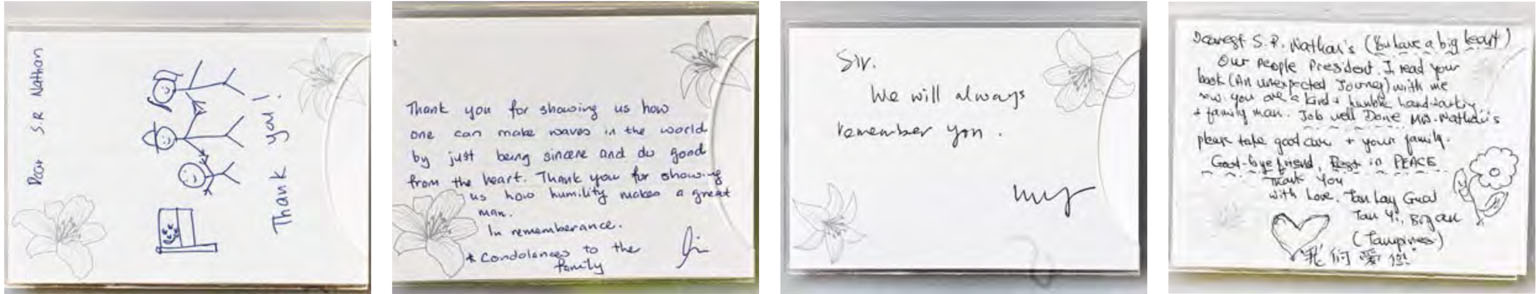

Already, he demonstrated the traits that would take him far in life: his independent judgment, boldness tempered with diplomacy and, above all, kind-heartedness.

The incident also typified his work ethos, recalled Mr Tan Eng Beng, 58, principal private secretary to Mr Nathan from 2005 to 2011 when he was president.

Each morning, Mr Nathan would carefully comb through the newspaper and whenever he came across a report of an individual down on his luck, Mr Tan was asked to find out how the person was being helped.

“He would open the newspaper and say, ‘Hey, this boy is sleeping at the bus stop, what are MCYS (the then Ministry of Community Development, Youth and Sports) and others doing to help him? Please tell me,’ ” he recounted.

The instinctive acts of compassion are Mr Tan’s most cherished memories of Mr Nathan, whom he saw for the final time on Monday afternoon at the Singapore General Hospital, hours before Mr Nathan died at the age of 92.

As his aide, Mr Tan had a front-row view of the former president’s relentless effort to fund the education of poor students.

He recalled a group of Malay students who did well and were admitted to prestigious British universities including Cambridge University and Imperial College London.

But they could not go on their own dime or that of self-help group Mendaki, which does not fund overseas education.

When he heard about their plight, Mr Nathan personally arranged for donors to pay their fees.

He went a step further and asked public agencies to give the students internships and jobs so that they would return to Singapore.

“He said we should do what we can to help them succeed in the universities there and then come back and be leaders of the community here in Singapore,” said Mr Tan.

Mr Nathan could also be counted on when aid schemes or groups like the Chinese Development Assistance Council did not pay for tertiary education: “He asked all these agencies and people to let him know if they came across someone who needed support.”

Mr Tan added: “He must have easily helped more than a hundred people this way over the years, without letting them know that he was the one supporting them. He never wanted to be acknowledged.”

Helping with an invisible hand was his way of living his strong belief that education improves lives.

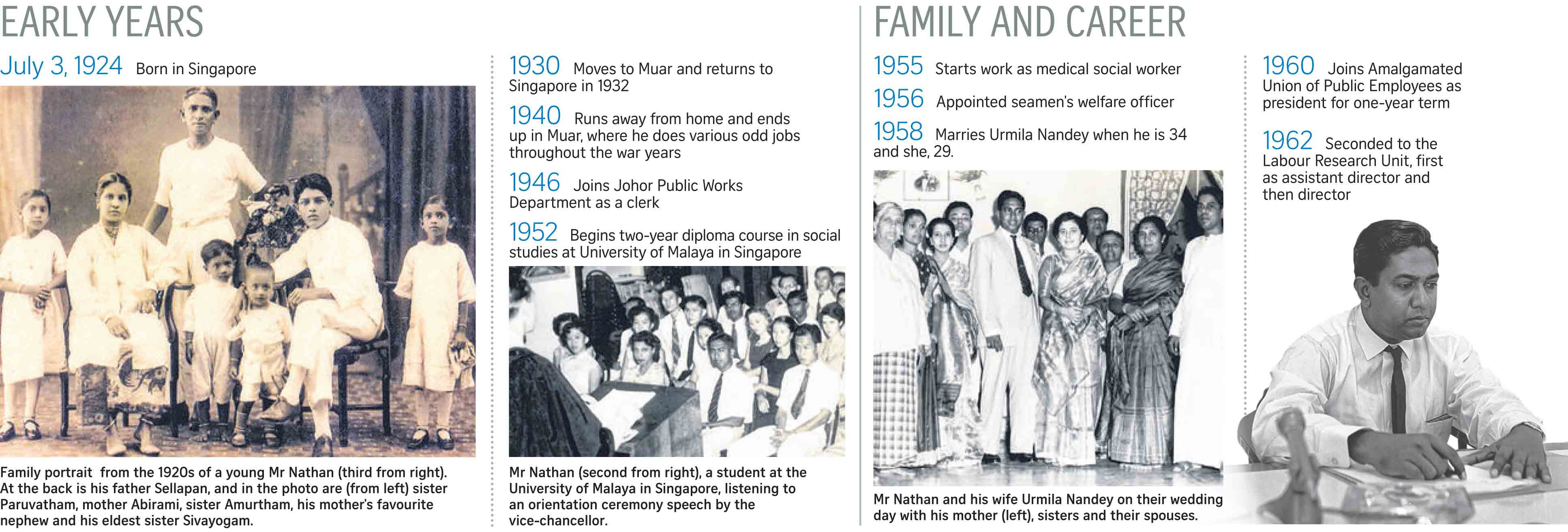

Growing up with little, he received a bursary from oil giant Shell to study social work at the then University of Malaya in Singapore. He was 28.

He also set up the S R Nathan Education Upliftment Fund in 2011 to support disadvantaged polytechnic and Institute of Technical Education students. Said Mr Tan: “He always wanted to give back.”

For Mr Nathan, no individual was too unimportant and no detail too troublesome to look at – two qualities that stood out in his work.

He was an exacting boss who held those under him to high standards, said Mr Tan. “Whenever he had any questions, he would call me over, and I had to be very clear about a recommendation or decision I made.”

He held himself to the same standards: no cutting corners.

He would meticulously examine every piece of legislation before he gave his presidential approval.

Recounted Mr Tan: “He scrutinised whatever the Government put up, to the extent that government agencies were sometimes quite unhappy with me because I was the one who had to query them.

“They would say, ‘Why are you asking all these questions?’ “

On state visits, Mr Nathan – a former diplomat – always had a foreign policy goal he wanted to achieve, said Mr Tan.

“He’s not just going there to have tea with the president of the other side.”

Part of his responsibility as president was to consider the clemency pleas of death row inmates, and to sign their death warrants.

“He would even call up the Attorney-General to make sure he was doing right by the person, that he understood the case and was not signing blindly. He had this sense of trying to be fair to everyone,” said Mr Tan.

Mr Nathan was unafraid to disagree when he felt something was not right.

For instance, he disagreed with the decision to build casinos in Singapore, and gave his views to the ministers of the day.

But he could see beyond his personal preference and accept what was for the national good.

This article was first published on Aug 24, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.