SINGAPORE: He is a medical doctor by training, and entered politics in 2011. Over the years, Dr Janil Puthucheary has spoken up in Parliament over a range of issues, including healthcare and national identity.

Following the 2015 General Election, he rose to the Cabinet, taking on posts as Minister of State for Education and for Communications and Information. Today, with a foot also in the Smart Nation Programme, and as chair of the Group on Disruptive Technologies under the Committee on the Future Economy, his mission is to help Singaporeans see digital disruption as an opportunity rather than a threat.

At a time when Singapore continues to face challenges amid economic restructuring, he is optimistic that through education and training, Singaporeans will be able to thrive.

He went “On the Record” with 938LIVE’s Bharati Jagdish about education policy, the PSLE, helping teachers cope with their workloads, changing parents’ mindsets and his entry into politics. They started first by talking about technology, and getting the Singaporean worker ready to ride the waves of change.

Janil Puthucheary: The pace of change is accelerating: The rapidity with which new technological innovations are not just being considered and developed but also being propagated across the whole world. Especially when it comes to software, digital products which are not physical in nature, there’s no barrier as to how fast they can move around the world.

The second thing is that with that pace of change, it is very hard to be sure what are opportunities and what are threats. Because a new product or a new service can come along and get people out of a job; similarly, it can open up a whole new industry. So that balance of uncertainty.

And the third factor that we’re considering is that in this new realm of the new digital economy and technological disruption, there’s really not a lot of space for people to move late and wait and see what works for the rest of the world, then get on the bandwagon. You’ve got to be moving right at the cutting edge. So you have a lot of uncertainty and a need to move fast. We have to think how can we strategise and plan for this in a way that takes that into account.

Bharati: You talked about people whose jobs are threatened. And right now, we are seeing that happen in various sectors including in the transport sector where taxi drivers are worried about the driverless vehicle phenomenon. Re-skilling is an option, sure, but what are the challenges you’re finding in getting people to embrace it?

Puthucheary: Hoping that things will always remain exactly the same is just not going to be a useful strategy. That requires a big mindset change and that means people need to be willing to be retrained and re-skilled. Once we cross that barrier, we have to make the opportunity available. SkillsFuture is a big part of this, to unlock a lot of that potential for training in many educational institutions. But also it’s working with employers and working with the industry so that when people get the training, it is directly industry-relevant, that people can have the assurance that this is going to help them get a job. So there are a number of parts to it.

You are right that as you consider workers who perhaps have not been a part of the digital economy or not part of the technological industry …

Bharati: … They actually feel a sense of resentment that Singapore is moving ahead with some of these initiatives.

Puthucheary: That’s right because the pace of change is really rather fast for them. And so, we have to work with them directly. We have to make training available in a language that they can understand. We have to think about what we can do. One example is people who need some foundational or fundamental math skills and that level of expectation of math skills was not part of the high school or secondary school that they went through 20 years ago. So sometimes, some of the upskilling we need to do is not necessarily directly relevant to an industry but it’s almost foundational and fundamental so we have to take all these things into consideration.

Now, the idea that, just because you are of a certain vintage, you can’t access technology and digital products, I think increasingly that is clearly not the case. We have grandmothers who are producing channels on YouTube and we have grandparents who connect with their grandkids on WhatsApp and so forth, and we have a whole bunch of services and products specifically designed to get the senior generation online. So we are addressing that with digital inclusion policies, Silver Infocomm programmes that we have in place. It’s working. An increasing number of these seniors are getting online and getting involved. So I don’t think that age is actually a barrier. It is more the angst and the anxiety that you’ve identified.

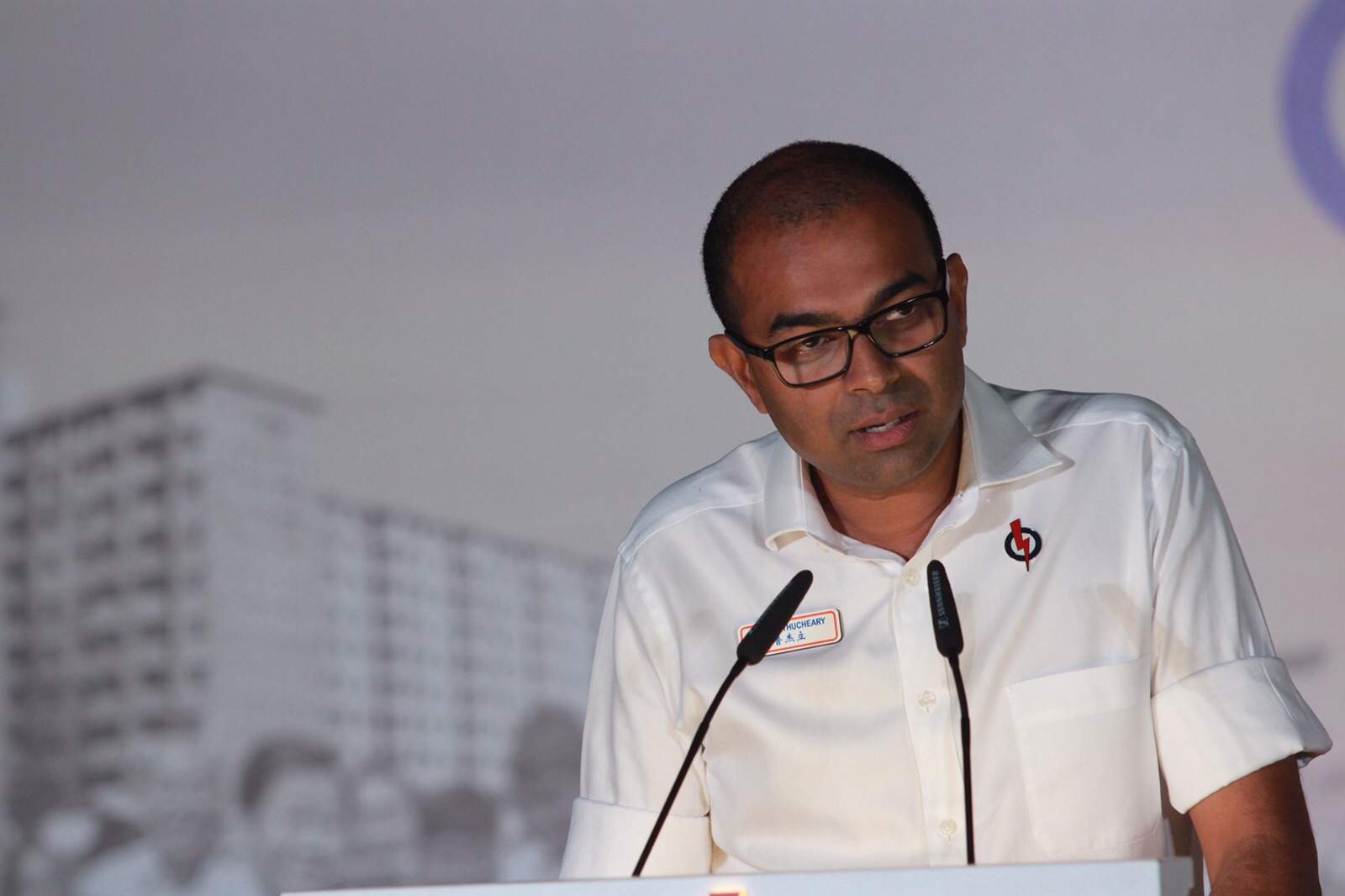

Dr Janil Puthucheary speaking at a special screening of Channel NewsAsia documentary Regardless of Race. (Photo: Wee Teck Hian/TODAY)

Bharati: Being tech-savvy in your social life or your family life is quite different from being tech-savvy professionally enough to work in an industry like that, isn’t it?

Puthucheary: Well, it is not easy but it needs to be done and it can be done. But increasingly, it is being done. If you look at the landscape out there, there are an increasing amount of senior workers who are able to make that transition.

Bharati: In some sectors where there are labour shortages, automation may be welcomed and even necessary, but to what extent do you get a sense that in some industries, some people actually don’t want technological initiatives to be implemented just so that existing jobs can be saved.

Puthucheary: You’re absolutely right. In any industry, the incumbent is always going to prefer that their current business model continues.

Bharati: Explain to them why it is necessary for this to change despite the fact that change might lead to a loss of their jobs.

Puthucheary: Firstly, a whole new series of domains, industries and jobs and businesses will be created that we never even imagined before. Secondly, life gets better. Life gets better for a variety of reasons in various technological revolutions because pollution is reduced, energy efficiency goes up, the value add goes up, the ability for people to be productive goes up. So this is always going to be the case and it’s not just about taxi drivers and autonomous vehicles. It’s any incumbent business where they are potentially disrupted.

But the key is going to be identifying opportunities early and be willing to participate in that change. You’re absolutely right: Whatever change that we have, whenever you bring in new technology, whenever you bring in an opportunity, there is going to be a concern of the job being lost. But there are also going to be opportunities for new jobs being created.

Bharati: How much of a challenge has it been to effect this change of mindsets so far?

Puthucheary: Well, the clearest view that I get is that they want to do this. It is just that they feel that the technical hurdle to doing so is quite high. The mindset is often not that they don’t want to do it, but it’s usually that they think it’s going to be too difficult for them to do. So it’s the latter that we then need to address – find them and train them and bring them into the space. We have to work with industry associations and sometimes we have to work directly with employers. We have to look at education, at the whole spectrum from secondary school all the way up to adult learning.

SINGAPORE “IN A VERY GOOD POSITION”

Bharati: Singapore has often been criticised for being rather utilitarian in its approach when it comes to education. That should be a good thing in terms of being able to gain skills that contribute towards greater employability. Yet, now we find ourselves in this position where our skills are becoming obsolete and many are losing their jobs. What do you think has gone wrong here?

Puthucheary: I’m not sure that something has gone wrong. The pressures are being faced by the entire globe. Because of our very rich ability in science, in technology and math and digital literacy, we’re actually in a very good position. If you consider some other economies where they don’t have such a base to move from, they’re going to have a big challenge. But because we have that strength in science, technology, engineering, mathematics, we are likely to be able to do well if we are prepared to do so. So our education system has served us well to move us up that ladder of science and technology, engineering and math skills. We’ve got a great foundation for that.

Bharati: But clearly it hasn’t been enough in terms of keeping up.

Puthucheary: Well, actually we are doing very well. The rest of the world looks at us and thinks we are ahead of them. It’s our own paranoia and our own divine discontent that our Prime Minister talked about. It’s a healthy thing. So actually, we are doing well.

If you look at the interest in coming to Singapore and developing a start-up here, it’s very high. People want to develop their products here. People want to do their R&D here. And it’s because we have people here who can do it. We have people here who can code. But it’s not just the hard engineering. We have good people who are able to look at the psychology of the interface, design the way games work with the users, the interfaces, the softer, interactive side of things, so we do have that rich pool of talent in Singapore. I think we are in a good position to take advantage of the digital revolution. We just have to push further.

Bharati: But there is a skills mismatch nevertheless.

Puthucheary: We are not saying there isn’t a skills mismatch. There will be skills mismatches any time you have this type of technological disruption, every time you have innovation that works. We want innovation. We want new businesses. That always is going to have a process of change and part of that change is going to be the skills that are in demand and the skills that are less in demand. So this is exactly what we are expecting, but we want to make sure that people have the opportunity to take advantage of it. And to take advantage of it through entrepreneurship as well, so there are initiatives to encourage that too.

We are projecting ahead and we want to make sure that looking ahead, we have opportunities to deal with skills mismatches. It is not that we are hoping that it is not going to occur. We know what is going to happen and we are planning ahead to deal with that skills mismatch.

It’s not going to happen immediately. It’s going to take some time to filter through. I think it’s not a simple matter of saying that this job description is safe and that job description is not safe. I think the reality is that in every job, there is the potential for change. What we’ll have to do is identify what are the skills within a given domain, where you frankly need a human being to participate and what are the things that are better driven by data?

Medicine, which I have some familiarity with, is a great example of where there’s a lot of stuff that has changed over the last five to 10 years. It is driven by data, driven by technology, yet if you want to make a decision, if you want to make a decision about your healthcare, you would, I imagine, prefer not to have an automated piece of software simply trawl through your data and simply say: This is what you have to do. You would want someone who you can bounce questions off, get a sense of trust and get a sense of caring and a participatory process. That requires a human interface. But it requires a different set of skills which is different from the purely analytical process.

So we may need a balance within medicine and think about how we can focus on a different set of skills. It doesn’t mean you don’t need doctors and you don’t need nurses and you don’t need healthcare professionals, but the balance and the type of skill and the tasks that they do will shift over time. So the way I would phrase it is that every job is potentially disruptable. It’s up to us to find something of human value within the job so that we do things that are meaningful.

Bharati: Let’s talk about education because it’s all rooted there as well isn’t it, and you said that you’ve got to look at it right from the start – the start of education from primary school all the way up. Clearly just focusing on one skill alone is not going to work and learning and relearning needs to be the norm. Adaptability needs to be the norm.

A lot is also being said now about nurturing people’s passions, but your passion isn’t always going to be something that will give you the skills that are in demand right now. How do you think all these objectives can be balanced in terms of education policy?

Puthucheary: Well, the first thing is that it is not a zero-sum game. It’s not that you can’t work hard and then therefore not have a passion. And it’s not that you have to only have a passion and not do something that may be useful to you in your life. There’s room for plenty of stuff to happen in one’s education as well as one’s life and one’s career. The starting point is that if people can do what they’re interested in, they are far more likely to put in that extra effort and work a little bit extra at being committed to it and staying the course and finding out the true depth of whatever it is, whether it is a hobby, whether it is a skill or whether it is a career.

So if you can match that self-belief and that self-drive with an opportunity, you are far more likely to have that person enjoy themselves through the meaningful work that they do. That’s one set of issues. But the second issue is that, whether it is something that you are led to because it is part of the course requirement or whether it is something you found yourself doing because it’s your passion, things can change over time and so we need to have systems and processes in place where we don’t see a single choice at one single page and that’s the be all and end all.

We have to have opportunities for several points of choice over time and if you are now interested in this and later on you find that it didn’t work out for you, let me go and do something else. But if that decision to do something else is grounded because you had the opportunity to pursue something that you found interesting, you’re far more likely to understand when is the right time for you to change and when it’s the right time for you to then build and do more of it and make the choice properly.

“YOU CAN’T LAY EVERY PROBLEM AT THE FEET OF THE GOVERNMENT”

Bharati: Right now of course, a lot of people are still very focused on academic results, getting into a good school, so on and so forth. How do you envisage the education system shaping up to encourage people to make choices, to allow them the latitude to do what you just described?

Puthucheary: That’s exactly why we’ve got some of the changes we’ve announced about the PSLE, DSA. So specifically, we want people to be able to do that, not focus on chasing those last few decimal points and have the schools have a little more variation in terms of the non-academic work that they do that the kids might be attracted to, whether it is music or sport or some other niche areas and at the same time, looking at the academic work that they do and finding ways to link them to real-world cases. And this is the applied learning programmes where if they are doing academic work, it can be linked to a variety of things. They can understand how those fundamentals can transfer to a variety of industries and be interested in them as something to do, not just something to learn.

Bharati: When it comes to education, the Government’s narrative seems to be that it’s trying its best to make school less competitive and less stressful, in terms of changes to the PSLE scoring system, and doing away with school rankings, but it is mindsets on the ground among parents and students that are hard to change. That’s the Government’s narrative, but of course, not everyone agrees.

Puthucheary: I think the question is how fast you expect mindsets to change. Someone’s inner beliefs and worldviews take a long time to change. It’s probably a good thing because it’s not your worldview if you are discarding it on a whim and a fancy. They are heartfelt and they must slowly be changing as a result of something. And these values and worldviews change because people see that there is value in a different way of doing things.

I think we increasingly see stories of people who have been able to focus on not just chasing that grade or piece of paper, but stories where they focus on building a team, building a process, building a business model. It’s not that those things I’ve described are not hard work, but they are a different model of what is important. Increasingly, people see that this is possible and that people can be successful through it; success being defined through a wider lens of fulfilment and satisfaction and happiness.

It’s about what people see and you’re absolutely right, it’s partly about the narrative and I think part of it has to be what we have in the popular culture and in this, I think, the media has an important role to play and you could help us in this! Every time we say that people are very stressed out and academic grades are all that matters, well, that’s the message people get.

Bharati: But wouldn’t you say the Government was responsible, to a great extent, for those entrenched mindsets to begin with?

Puthucheary: I think it’s the role of Government to provide an education system that drives a national benefit and it has done so. You can’t lay every single thing at the feet of the Government. There are plenty of governments around the world who don’t have the focus that we have had on education, in the way that we have had, but you find just as much educational stress among the young and parents. It’s not just because of policy and it’s not just because of our education system. The reality is that every parent wants the best for their child. The question is: Do they understand what that “best” is and what the options are for that “best”.

In Singapore, we are still at the stage where the change in one generation is still very significant. Kids come home with homework or reading assignments that their parents have difficulty understanding. So for that parent to then have a very relaxed worldview, where they don’t fundamentally have a good understanding of the work that their child is doing, I think that it’s a big ask. It’s going to take them some time to have that confidence that their child can find their way in a very new world.

So that pace of change over three generations is very significant and think it’s perfectly understandable that it drives some anxiety. We need to find ways to then deal with the anxiety rather than trying to find a singular source of blame.

Bharati: You’ve mentioned changes to the PSLE and while some appreciate it, many other parents said the changes wouldn’t make any difference in terms of stress levels. To what extent do you feel that parents should manage this on their own or is there potential for the Government to do even more in terms of setting the tone?

Puthucheary: Well, I think there’s a balance between the Government and the education professionals and the parents. I think from an education policy point of view, we’ve got some plans with PSLE and it becomes an opportunity then to shape conversations between families and the teachers of those children and have those teachers and those families interact around this change and see this as a way of changing attitudes.

It is not a silver bullet and it shouldn’t be. There’s no one thing that you can do that is going to wipe all stress and anxiety. It’s impossible. It’s a matter of how we deal with that stress, how we deal with that anxiety and how we behave toward the balance between that stress and that academic process.

I think the issue with the PSLE is that the focus has been on the Achievement Levels. But to me, one of the more significant changes, I would argue the most fundamental change is the move from a norm reference to a standard reference. Now that’s a very technical point but actually from a philosophical point of view and driving this conversation is the idea that any given child now is purely graded on their efforts and not in relation to their peers. That is a big shift. It’s a big change in the way we do these national exams. I think if we can ride on that and explain to parents and have that conversation between families, principals and teachers, this is something we can manage.

Dr Janil Puthucheary on the Channel NewsAsia documentary Regardless of Race.

HELPING TEACHERS MANAGE HEAVY WORKLOADS

Bharati: Since you mentioned teachers, they are pivotal in these efforts. You’ve commented on the role of teachers before – that they need to be facilitators and not instructors in order to improve the way students learn and grow. Considering that teachers today also struggle with heavy workloads and all sorts of demands, what do you think needs to be done to help teachers be effective facilitators to shape a new type of student for the future?

Puthucheary: NIE is a jewel. It’s a wonderful example of some of the things that we have been able to do in our education space. And it does some very, very good work and one of the things NIE is really very good at doing is updating itself and changing the way that it trains teachers and updating the way that the teachers leave NIE with new pedagogical tools, new techniques, new methods of how to engage with the classroom.

Now, having said that, education in this new age is not just about doing new things. Some of the ways that we were taught – not everything was bad, there were a lot of fundamental instructional techniques that have been relevant for many decades and that are still relevant today. So it’s not about throwing everything out and pretending that we just have to start from scratch. It’s about finding those things that work, and keeping those going, and then having the ability to then be very agile and very nimble. That is what happens in the relationship between how NIE does its work and what happens in the postgraduate professional development that our teachers have as a result of the current structure, where the teachers get 100 hours of professional development time every year.

Now, how that relates to the issue of workload or stress – this is an important issue for us to consider and we do have to make sure that our teachers have the opportunity to do the meaningful stuff and find ways to be either delegating or reducing the routine administrative stuff. This we can do through ICT products and services that we can help develop at MOE HQ and we are producing an increasing number of those. A number of schools have gone out and commissioned their own ICT products and are experimenting in that landscape, so there’s quite a lot of that stuff happening.

But part of professional development is to help teachers manage this aspect of their life – the administrative overheads, the organisational issues, the workload issues and so having that ability to then have that professional development not just focused on instructional quality or teaching quality, but on how do you manage your time, how do you manage your stress, how do you manage the workload. That is also part of what we should do. It’s a policy of having a proactive approach to make sure teachers remain upgraded and at the top of their game along the way. And it’s an approach from an organisational point of view to try and reduce those administrative burdens. Now, that is a moving target. That is going to change and that’s always going to be an issue as we have all kinds of things happening – new CCAs, new activities, new programmes. So that requires a very personal approach by the team and the staff.

One of the biggest burdens for teachers is the stress of dealing with us, the parents. I’m a parent myself and my apologies to all my children’s teachers. I hope I have not added to your stress.

Bharati: You don’t WhatsApp your children’s teachers in the middle of the night, do you?

Puthucheary: No, I do not WhatsApp my children’s teachers in the middle of the night. That’s exactly what shouldn’t be happening. I think we need to do a little bit more in recognising the professionalism and the excellent calibre of teachers that we have in our education system. I can say that as a politician in MOE and I mean it, but I think as parents, we really need to respect it and live it a bit more. I think that will go some way to helping relieve the burden of the teachers.

Bharati: What about things like making sure there are more allied educators in schools, more administrative staff to help teachers. Why is that a challenge?

Puthucheary: We are looking at having allied educators, but more is not always the straightforward answer. Some of the administration has to be done by the person involved. So if the administrative issue has to do with your class, we do need the person managing or running the class having scrutiny over that administrative information. If you then have another person come in, it may actually add burden.

This applies not just to teachers but it applies across any number of professions. We can look at the pure skill of it and we can look at the sort of the administration and the managerial part of it. If it is easy to separate and have professional administrators do it, we should. But there’s always going to be some parts of it where really the professional skill and the administrative workload actually has to synchronise.

Bharati: In some cases, even some teachers will say “it would be easier if I did it myself”. But simple things like organising certain class events, filling up forms or chasing parents for consent forms, surely can be handled by someone else.

Puthucheary: Well, forms are a big bugbear and I would dearly love to take forms and digitise as much of that as possible. I think it is one of the great examples where we can break past some of the barriers we have. So some of these are things we are studying at MOE. What we can do is try to remove some of these burdens, come up with some new products that may be of use, allow some customisation to deal with the workload issue.

ENTERING POLITICS IN SPITE OF OBJECTIONS

Bharati: When you first came on to the political scene, it was reported that you had promised your wife that you would never enter politics because it would take time away from family life. Refresh our memories as to why you broke this promise.

Puthucheary: Well, depending on your technical argument, I would say I was released from the promise. I think the involvement in politics was something I felt very strongly about and I felt it was something important to do. Frankly speaking, it was not something I ever imagined myself doing. So perhaps something for which I had to go and seek some forgiveness and understanding from my wife.

Dr Janil Puthucheary with fellow Pasir Ris-Punggol GRC Members of Parliament (MPs). (Photo: PAP)

Bharati: You said it wasn’t something you ever imagined yourself doing. Why not?

Puthucheary: I don’t know. I was a doctor and I was wholeheartedly in that world.

Bharati: So what was it that made you want to do it, considering you never even imagined it previously?

Puthucheary: I started doing some volunteer work and participating in some community work and I volunteered at one of the Meet-the-People Sessions with Sam Tan, and over time it opened my eyes to a whole bunch of things that was outside of my professional experience, outside of my experience with the world of medicine. I found it very important. It impacted people in a meaningful way and there was a lot of good work and important things to be done.

It wasn’t that I woke up one day and suddenly I was doing all this stuff. It was a very incremental process over time. And so, it was exactly that. Incrementally, over time I got more and more involved in something outside of my comfort zone, found it very engaging, found it very meaningful.

I had done quite a lot of volunteer work up until that point, mainly medical missions. And I was speaking to someone and this person made a comment about breaking out of my comfort zone, finding meaning in work that made you a bit vulnerable and a bit anxious as whether you could do it well. That kind of piqued both my conscience and my curiosity at the same time. So I thought I would look for an opportunity to do something that was quite different.

Bharati: Was there any one thing in particular perhaps that made you feel that you could be of great value here.

Puthucheary: No, I have to be honest. I can’t say that I can identify one day or one particular incident. It really was over time and it was a series of things. You help one person and it seems to work out well and then you have somebody else whom you didn’t manage to help but they really appreciated that someone gave them a listening ear and understood their problems and you helped another person, and it was kind of a little bit and a little bit.

Bharati: Your father was a trade unionist. He was a founding member of the People’s Action Party (PAP), but subsequently left the party and was at one point, detained under the Internal Security Act (ISA). You said in 2011 that when you broached the subject of entering politics, your father did not allow you to finish explaining. He said: “I’m very proud of you. It is not about which side you are on, or picking sides. It’s about being prepared to step up and stand forward and be part of the struggle to make it a better world.” But were your father’s potential objections something that you were concerned about nevertheless?

Puthucheary: It was not something that was inconsequential. If you remember the 2011 election, it wasn’t brought up as a particular issue among the electorate. I was actually more concerned that it would be more of an issue for my dad. Whether that was the right assumption before the election or not, I don’t know. But anyway, he was quite supportive and actually very enthusiastic about my involvement. I suspect, in the same way, that I have never seen myself outside of medicine, he may have wanted me to do things outside of medicine for some time. He seemed very enthusiastic when I was getting involved.

IDEALISM VS PRAGMATISM IN POLICYMAKING

Bharati: You were also asked about your views on the ISA at that point and you said something that up until today is sometimes quoted on social media. You said that while you could discuss the philosophical aspects of the law, the philosophy is not as important as the pragmatic implications for the state. But considering public discourse in Singapore today, to what extent do you think philosophical questions and perspectives on issues need to be considered more so than before? Not just when it comes to the ISA but in politics in general.

Puthucheary: Well, firstly, when people bring this up, there’s this assumption that it is not considered. I would argue that it is considered. It is not that the philosophical point of view or the moral point of view or the values involved are not considered. But people who object to how we do things, take a very purist point of view, that we shouldn’t be considering the pragmatic value. The reality to my mind is not that it is either a purist philosophical point of view or a pure utilitarian point of view. You need to be discussing and having multiple viewpoints but ultimately, you can have all the viewpoints you like, you need to then decide on a specific course of action, a specific policy point of view.

Now, if you are a purist, anything that includes a hint of pragmatism is going to be wrong. If you are a pragmatist, any involvement of the philosophical or the moral point of view is fine provided you can also come up with a pragmatic and practical outcome.

So here you have a disconnect between two very significantly different worldviews. I think we can do some work to bring those two worldviews together. And I would return to where I started – the idea that we don’t consider philosophy and the moral point of view, it is frankly wrong. We do have very significant views on what are the values that inform our national identity, what are the values that inform how we, as a people, should take a given question forward. Now, should we have more philosophy, more values, more moral judgement? Well, you can always discuss more. But what I think we can’t have is to then have no pragmatic point of view. I mean at the end of the day, a philosophical point of view is only correct for those people who hold that point of view and not everybody holds the same point of view. In Government and in politics, you have to be able to then have a pragmatic, practical way forward that will accommodate a variety of points of view.

I think we have to do what works for Singapore. We have to do what works for our people. I think many of the people who reject that point of view are taking a very singular moral and philosophical point view. They are taking a point of reference, often external, and holding that up as the ideal. I think there is no absolute either way. We are not absolute pragmatists. We are not absolute idealists.

Bharati: You think we have the right balance?

Puthucheary: Well, the right balance is always going to be a moving target. By definition it is. That’s what pragmatism is. It’s the fact that you’re open to revising your point of view, revising where you’ve landed on a given subject and changing your view over time as the circumstances change, as the facts change, as the reality changes, as the pressures change.

I would argue that there is quite a lot of discussion going on. Could we have more? Well, we can always have more. But I think it needs to be informed. It needs to be grounded in the right values, and it needs to be open to accommodating the breadth of viewpoints that are the reality of Singapore.

Dr Janil Puthucheary speaking at a PAP rally during the 2015 General Election. (Photo: Xabryna Kek)

Bharati: How would you apply this way of thinking to calls for political diversity in parliament?

Puthucheary: Well, one of the values that informs political diversity is diversity for diversity’s sake in politics an end in itself. In other words, are we willing to drop all other criteria just to have a greater number of opposition members in Parliament? I think most people would argue that the answer is “no”. Would we need to ensure that anybody who comes into Parliament has a particular standard? The answer most people agree is “yes”.

The reality is that there is no systemic obstruction to that process. We have a parliamentary democracy which is based on a competitive adversarial nature between two or more parties. And that competitive nature means that we all have to maintain our standards and if we are then able to meet the higher standards which is that a voter selects us, then we can come into Parliament.

Having said that, the reality is that we have made some moves to have diversity of voices. Not necessarily political diversity but a diversity of voices. We have the Nominated Member of Parliament (NMP) and the Non-Constituency Member of Parliament (NCMP) scheme and so we have a variety of voices, a variety of viewpoints in Parliament and the reality is that those two schemes actually bypass that standard of the voter being the one choosing you to go to Parliament. So this is a great example of that balance between pragmatism and the idealism.

The idealism of representative democracy is that you do none of this. You just simply let the people decide and in fact, you don’t even then ask yourself the question of what we should do to get more opposition in Parliament. The idealist point of view is that the people should make the choice about whether the opposition come in. But here, you have a very pragmatic balance between that hyper-ideal view and the reality that we need some voices to come into Parliament to speak on a variety of issues and not all of them need to be political.

DEALING WITH PUBLIC SCRUTINY

Bharati: Another issue that came up when you ran in 2011 and that comes up even today in public social media comments, is that you never did National Service (NS). To what extent are you affected by such comments?

Puthucheary: Well, you choose whether it affects you. The reality is that whether there is a real issue there and whether there is something grounded in fact or if there is a miscommunication or misconception. I’m a new citizen and as a first-generation new citizen, I’m not allowed to serve NS. There is no issue there. It’s not that I had the choice to do so and I failed to do so. I am not allowed to do so. To my mind, this was an issue of communication and perception and it had to be dealt with in that way and I think it was dealt with in that way. You’ll know that I did volunteer for the SAF Volunteer Corps.

Bharati: The question isn’t so much about the NS issue, but more about how you deal with this sort of thing. People talk about politicians, flame them online, say all sorts of things about them. Does it bother you on an emotional level?

Puthucheary: Not particularly, no. First thing is to make sure the facts are correct. Even for journalists, to make sure they understand the facts and understand what the facts are. Then you’ve got to work out whether there is a real issue. You can be flamed for something that is real, in which case you need to go and fix it and find out what the problem is. Or you can be flamed for something that is created in which case you’ve got to take it with a pinch of salt and move on and deal with it as one of the things that is part of the rough and tumble of politics.