SINGAPORE: The normally light-hearted, witty and fast-talking Neil Humphreys pauses for moment. He looks increasingly perturbed as we discuss why, for all the love that he professes for Singapore, he hasn’t fully committed to the country by becoming a citizen. At times, he is almost defensive.

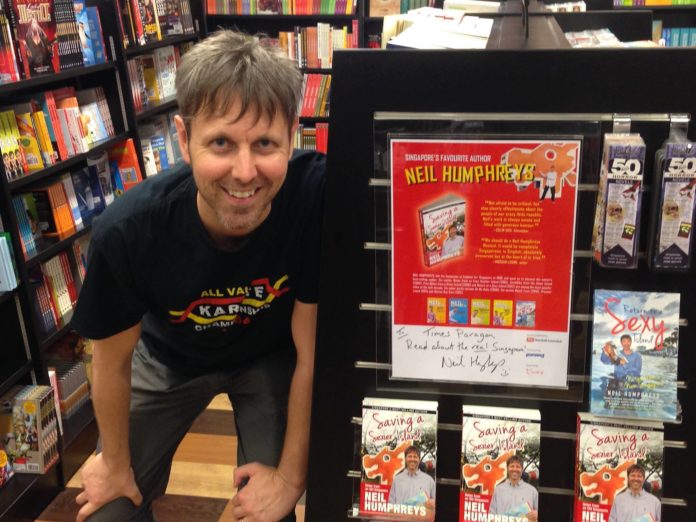

While he’s unassuming, often seen in a T-shirt, jeans and sneakers, Neil Humphreys’ tall and lanky frame guarantees that he stands out in a crowd. In a sea of largely Asian faces in Singapore, the Caucasian also stands out simply because of his race.

In every other way, he likes to think he has assimilated.

In his 20s, Humphreys was hit by the travel bug. While studying at the University of Manchester, he became friends with a Singaporean who let him stay at his late grandparents’ home in the city-state. It was 1996 and he had planned to stay here for only 3 months, but fell in love with Singapore immediately and ended up staying for 10 years.

He lived in the heartland of Toa Payoh all that time and among his favourite everyday hangouts are hawker centres. He is the friendly ang moh with no airs about him. He has more or less mastered Singlish and during this interview with me he uses words such as “tekan” at times. Among his friends are local taxi drivers and hawkers. While he left in 2006 to go to Australia for five years to “scratch a travel itch”, it was Singapore he came back to.

“I feel Singapore is home. Sometimes, it really is as simple and profound as that. When I go to Changi Airport, it’s home. I’m in the hawker centres its real, it’s natural, it’s home,” he says.

A “SINGAPOREAN” WRITER?

In an interview with another publication a few years ago, he even said he’d like to be known as a “Singaporean writer”.

There is no doubt that he is prolific. His many works on Singapore include Notes from an Even Smaller Island (2001) and Saving a Sexier Island: Notes from an Old Singapore (2015). He has also written two football novels, thrillers and children’s books.

But Humphreys is not a Singaporean. After all these years, he is still a Permanent Resident (PR), and has not attempted to become a citizen.

“I feel like I’m being pressured,” he says as I attempt to find out why he hasn’t taken what would seem like a natural step for someone who claims to love this country and calls it “home”.

Some might say his reason for not seeking citizenship is perfectly understandable. While his wife and daughter live here, the rest of his family still lives in the UK.

“Last year, there was a very unexpected and sudden death in my family. It was an accidental death and out of respect for my family, I don’t want to talk anymore about that.”

“But because of that, I needed to get to the UK instantly and urgently and I needed to stay there for an undetermined length of time.

“That brought home to me that I still have all of my family in the UK, my parents, my wife’s parents. Being a PR helps me go between the two countries. If I had to stay in England to look after my parents for six months, a year, two years or whatever, it would be a lot simpler if I still had a British passport.”

The unfortunate death that led to this realisation however took place only last year.

Humphreys had lived in Singapore for many years before that. Why hadn’t he ever thought of becoming a citizen before this?

HE CONSIDERED CITIZENSHIP

“We felt like foreigners in the UK. I could not wait to come back and my wife was exactly the same,” says Neil Humphreys. (Photo: Facebook / Neil Humphreys)

“I looked into citizen issues but I was always aware that I have aging parents. I have a British citizen friend who lived in Singapore for many years. He married a lady from Thailand and she has had enormous visa issues, even though she’s married to a British citizen.

“I wouldn’t want to be in a position where I’d have to be in the UK for a long period of time, dealing with grief and having to deal with long-term visas as well,” he says.

“It’s a pragmatic, logistical and administrative thing. I have no problems becoming a Singaporean citizen. I possibly see that happening at some point. But while my family is still in the UK, it’s difficult.”

He claims he does “everything else”.

“I pay my taxes. I get all mushy on National Day. I cried when Joseph Schooling won the gold medal. If Singapore plays England, in any sport, I want Singapore to win.”

Assimilation was effortless for him.

“I just swapped one working class culture for another. I also grew up in London where everybody was a different colour, Indians and Chinese and Bangladeshis and Pakistanis so it was no big deal to me, to eat in a coffee shop in Toa Payoh.”

We discuss whether he ever thought of moving his family here.

“You’re talking about people in their late 60s, early 70s. They’ve lived in the UK their entire life, they’ve lived in the same town their entire lives. The culture shock would probably kill them. I have enough issues with them on holidays when they come and they come here two, three times a year. To them, chicken rice is exotic.”

Humphreys taught English at a local school when he first came to Singapore and proudly says that he needed the help of a Singaporean coach to neutralise his Cockney accent.

He then started writing for a local football fanzine. It was working for the fan club that brought him in contact with local journalists. He applied for a job in the media and became a full-time journalist and writer. Today, he freelances for various media.

He attributes his success as a satirist to having grown up “in a very funny household”.

“I grew up in a culture and an environment and a school system that encouraged us to speak out and encouraged us to laugh at ourselves.”

His wife currently teaches at an international school here and his daughter is a student at the same school.

To not go to a Government school was not a deliberate decision.

“My wife was teaching in a local school with me in the beginning but she had a friend who worked at this international school that was looking for people. She had worked there before we went to Australia. While we were in Australia, they asked if she would come back and said they’d have a place for my daughter as well. My kiasu light bulb went off. We felt that’s perfect. They can go to school together and come home together.”

“It was just a convenience thing. My daughter takes a lot of classes outside school. She just started an aikido class at the community club. She’s exposed to Singaporeans. Integration is not an issue.”

NATIONAL SERVICE

A few years ago, Humphreys even considered doing National Service.

“Because I always get that: ‘You ang moh, arh? You never do National Service what.’ That’s the only stick left that Singaporeans have legitimately got to beat me with.

“I had a meeting with some people from MINDEF and some TV people about the possibility of me doing Basic Military Training. The TV people were considering making a documentary out of it. I was running out of time, approaching my 40th birthday. But at that time my PR status hadn’t come through yet, so there were some issues with that.

“Now I’ve passed the age.” He’s 43 now.

NOT HERE BECAUSE HE COULDN’T “HACK IT” ELSEWHERE

Neil Humphreys has published 17 books across various genres. (Photo: Facebook / Neil Humphreys)

After graduating from university in the UK, Humphreys worked as a stockbroker for six months in the UK, a job he claims paid him well.

He asserts he’s not one of those foreigners who couldn’t make it in his own country and came to Asia to “rip off Singapore”.

He claims he has options even today – job opportunities from media organisations in the UK and Australia.

His books have done well in those countries as well. But he says he continues to choose Singapore and he does so because he truly loves it here, not because he can’t “hack it” elsewhere.

“I’ve said before that if I meet one more foul director, foul writer, foul producer, foul commentator, or foul teacher who couldn’t hack it in their own country and then came to Singapore and get a nice cushy expat job, I don’t know what I’ll do.”

Cushy expat packages are less common these days anyway.

WHITE WAS RIGHT

He admits the deferential attitude Singaporeans had, especially in the 90s, towards Caucasians had a part to play in his success. It helped him be heard.

“I’ll never lie about that. In the early days, I sensed people here were interested in me. It was more apparent to me because I’d come from a working class background back home where I was essentially written off as trash as soon as I opened my mouth. Then I came here and suddenly everybody listened to me. In the early years, white was right. That has thankfully faded now.”

But he claims that the deference and novelty, rightfully, didn’t last.

“If my work had no substance, my skin colour wasn’t going to save me. Maybe with my first book, yes, there was a slight novelty factor, but that novelty ended a long time ago.”

He cautions against being wowed by “ang mohs” with no substance, but “can talk for weeks”.

“Ang mohs are constantly encouraged to speak up and that’s not always the case in Singapore. So when they come here, they’re very confident in front of a crowd or a business delegation whereas a Singaporean, even some of our politicians, are quite timid, they can’t sustain eye contact. That’s a real problem. We need to fix that.”

In 2006, Humphreys left Singapore to go to Australia where he became increasingly bored.

“Within about two or three years of being in Australia, I got homesick for Singapore. I went to the suburbs of Australia and I was basically cutting the lawn and waiting for death. It wasn’t for me.”

A STRAWBERRY COUNTRY?

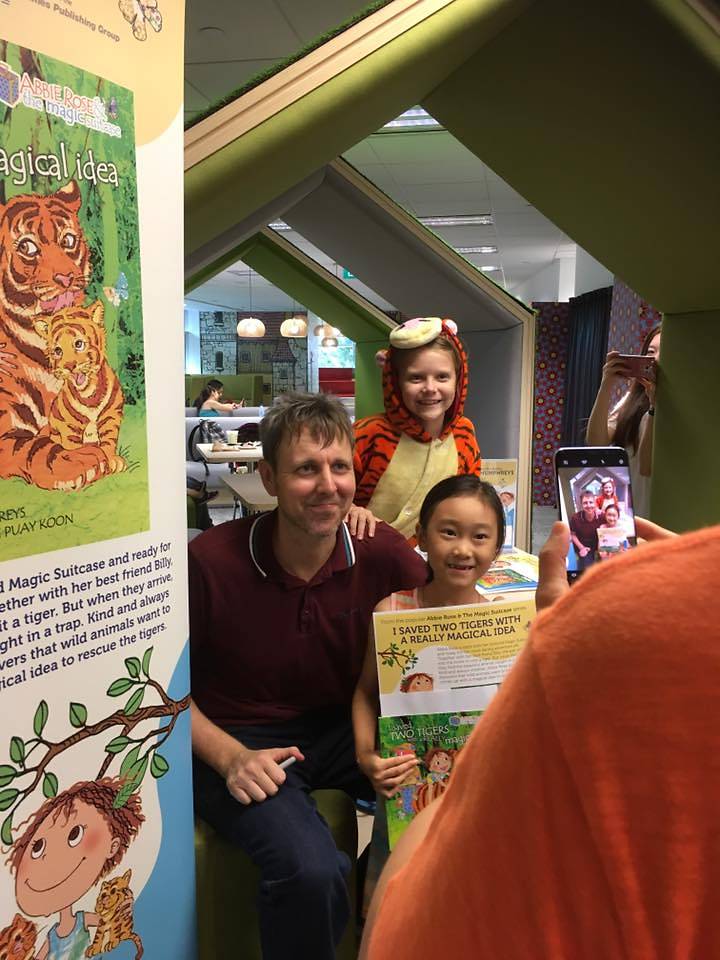

Neil Humphreys’ children’s books have garnered him adoring young fans in recent years. (Photo: Facebook / Neil Humphreys)

“I want the vibrancy and the colour of a 24-hour city but I also want the safety and security that you often get in most suburbs and villages. Singapore is one of the few cities on Earth that has that.”

Singaporeans take this for granted.

“I grew up in England. I was mugged twice. A friend of mine was killed in a nightclub incident, so I don’t take things for granted. When I say this in colleges here, I get the collective eye roll of restless 18-year olds who cannot wait to leave the boring, sterile Singapore. Leave. Explore the world and then see if you still take Singapore for granted.”

There are many other things he feels we take for granted.

“We’ve become a ‘strawberry country’. We complain about the MRT being four minutes late. Guys, get a grip. See what’s happening just in the neighbouring countries before you wreak havoc on social media.”

Still, chronic train breakdowns he agrees are a real problem.

“When we start to see alarming levels of inconsistency with the public transport system, that is different. But if it’s just a little late, is it so bad?”

When he moved back to Singapore in 2011, he moved into a condo.

As a PR he couldn’t buy an HDB flat immediately as HDB rules stipulate a waiting period of several years.

“I refused to pay rent to parasitic landlords for a moment longer. So I had to buy private.”

But he’s not living in an “ang moh enclave”.

“I’m on the border between Buangkok and Seng Kang. I’m back to being the only ang moh in the village. I’m walking distance from five coffee shops and hawker centers.”

“WE FELT LIKE FOREIGNERS IN THE UK”

So what’s his long-term plan? Does he plan to eventually return to the UK?

Again, his defences to go up.

“I feel like I’m being bullied now. I don’t know why.”

He claims when he and family went back to the UK last year, it became clear that they “no longer belong there”.

“We felt like foreigners in the UK. I could not wait to come back and my wife was exactly the same.”

“I’ll continue to travel because I love to travel, and if a job opportunity comes up in say Manhattan, I’ll go and work there for one or two years, but Manhattan won’t be my home. Singapore is my home. This is my base. There is no other home I can potentially foresee.”

There’s a deeper reason for his loss of love for the country he was born in.

“At the risk of upsetting right-wing leaning British expatriates, Britain has changed. It’s gone through a fundamental shift pre- and post-Brexit. There is very much a kind of ‘you’re either with this or against this’ type of thing. It’s becoming more insular.”

He says what bothers him is the hypocrisy he witnessed even among his own family members who voted for the Brexit.

“They say there are too many foreigners in our country. They need to go home. Those same people in my family used Polish contractors to do their kitchen and their bathroom because the foreign workers did the best work for the best salary.”

CHAMPIONING THE WORKING CLASS

But aren’t we seeing a similar dynamic in Singapore?

“I’m just too wary of excessive nationalism. We’re not there in Singapore yet. There are nuances to the issue here.

“I come from and still see myself as a working class guy, so I will always champion the working classes of Singapore. If a foreigner and a citizen are equal for the job, then the citizen should get it. That’s the issue in Singapore.”

He admits that this means some of his foreign friends in Singapore would be jobless. He himself is self-employed, so he has no skin in that game.

“But if it’s jobs that Singaporeans don’t want to do, and we have foreigners doing them, then you can’t use their services, but tell them to leave the country.”

A TICKING TIME BOMB

He cites the rich-poor divide in Singapore as a “ticking time bomb”.

“We can’t keep ignoring it. Wages are stagnating, hawkers are earning the same, retail employees are earning the same that they earned 10, 15 years ago but everything else has gone up.

“We have one of the lowest taxes in the world and you don’t see many Singaporeans campaigning to put our taxes up. I would pay more tax if it meant that certain HDB properties like hawker centers and other things like hospitals, whatever became a little bit cheaper. But until that happens, we might have to pay more for services.”

Clearly, while Humphreys loves Singapore, he also doesn’t hesitate to criticise it.

“You should be able to criticise. My wife loves me but she could sit here all day and list a thousand things about me that drive her mad. Love doesn’t mean you should be blind. Yes, you love a person, or a country dearly, but you love them enough to acknowledge the quirks and the nuances and the inconsistencies. That’s true love, to recognize flaws and hopefully try to address them and improve them.”

When asked what else he loves about Singapore warts and all, he talks about Asian values like filial piety.

“Respect for your parents, look after your parents, grandparents, also aunties and uncles in the street. They’re given a certain level of deference that I think we are losing in the UK, sadly.”

Neil Humphreys with students of Bartley Secondary School, inspiring a new generation of readers and writers. (Photo: Facebook / Neil Humphreys)

Education is another.

“Not to the kiasu degree. I’m not a big fan of tuition at all. But I do cherish the importance and the value of a quality education. I grew up in a society, a working class culture where there was no emphasis on education. We, in Singapore, tekan ourselves like nobody I’ve ever seen about the education system, but we also recognise our system as being one of the best in the world. So why do we need a ‘top-up’ through tuition?”

In spite of his working class roots, he made it to university in the UK.

“Because I was the beneficiary of the last of the government grants. That made it possible for me to get my tuition fees paid for by the government.”

As we end our conversation, Humphreys suggests more issues he thinks need to be urgently addressed in Singapore.

“We have to start in the year 2018 as a First World nation, starting to talk about the sensitive issues to avoid a potential Brexit-type situation down the line.

“We need to listen to those who ordinarily don’t have voices and we need to get the discussion going.

“I’d like to see more open discussion shows both on the mainstream media and the social media. We have this intellectualism obsession that we must always have a guy on a panel show that has a few letters after his name, a professor. I want to hear real people talk about real issues. That’s it.”

Being real is what he too aims to be remembered for. “Just an honest speaker, honest writer who wrote the best he could.”