SINGAPORE: A recent debate on whether Singapore should have more single- and twin- bedded wards in state-subsidised nursing homes signals that changes in the care system could happen.

Societal expectations are shifting – not just to emphasise more privacy and autonomy for the elderly – but also in favour of more holistic, home-based care, over clinical and regimented institutional approaches.

“We have seen a rising trend of seniors choosing home-based care,” said a Ministry of Health (MOH) spokesperson, adding that demand for home care is expected “to continue to grow in tandem with increasing aged care needs”. MOH-subvented home health providers served about 6,800 subsidised clients in 2015, up from about 5,800 subsidised clients in 2014.

This is trend is not unexpected, given the high rate of homeownership in Singapore. But while ageing at home is ideal for those in good health, it can be a challenge for those with physical or mental impairments.

How do caregivers do what is right by an aged parent, or sibling, who has expressed an aversion to institutional care? Channel NewsAsia spoke to two families who made chose to reject institutional care, to find out how they coped.

Mdm Leela: Bedridden and living at home with family

Leelavathy Muttutamby suffered a stroke in July this year, and had spent three weeks in a public hospital when the situation took a turn for the worse. The hospital advised the family that Mdm Leela would be referred to a community hospital for step-down care, as there was not much more that could be done, due to her high-risk status.

“The ischemic stroke converted into a hemorrhagic stroke. So from a medical perspective, my mom, who is 84 years old, with a bleed in the brain, has multiple co-morbidities, kidney failure (and) in any medical textbook, this is very poor prognosis or poor quality of life,” said Mdm Leela’s daughter Kavitha (who asked that her real name not be used), who is medically trained.

But the family eventually decided not to go with the hospital’s recommended approach.

“As a family we came together, sat down and talked about it, and we felt it was important that she be with us in the family environment, and that we have access to her easily,” explained the 53-year-old.

Mdm Leela (right) has made much progress since being discharged from the hospital in August (left).

Four months on, Mdm Leela has improved. The retired teacher no longer requires tube feeding, and is beginning to regain speech.

Kavitha believes that being in the home environment, as well as seeing and feeling that the whole family is in it together, gave her mother greater determination to fight on. “I told her ‘I haven’t given up on you, so you don’t give up on me,’” she added.

How they made it work: Kavitha, who is widowed, lives with her teenage son and her domestic helper of seven years. She hired a second domestic helper in anticipation of Mdm Leela’s move home.

“Prior to my mum being discharged, the nursing staff at the hospital did changing and bed care training for my helpers and me, and also taught us how to do tube feeding, give basic physiotherapy and occupational therapy care. We followed the instructions at home and did up a schedule,” she said.

Kavitha, who has a full-time job as a senior management executive, also engaged private home care service Jaga-Me for advice on transitional care arrangements. Jaga-Me currently provides monthly respite care to relieve her domestic helpers. When needed, they also connect the family with ambulance services, and doctors who do house calls, for example.

Caring for Mdm Leela at home did initially take a toll on the household of four, as they struggled to work their lives around Mdm Leela’s care schedule, said Kavitha. “There’s a whole host of things to learn for caring for a person who’s bedridden, who has had a stroke.”

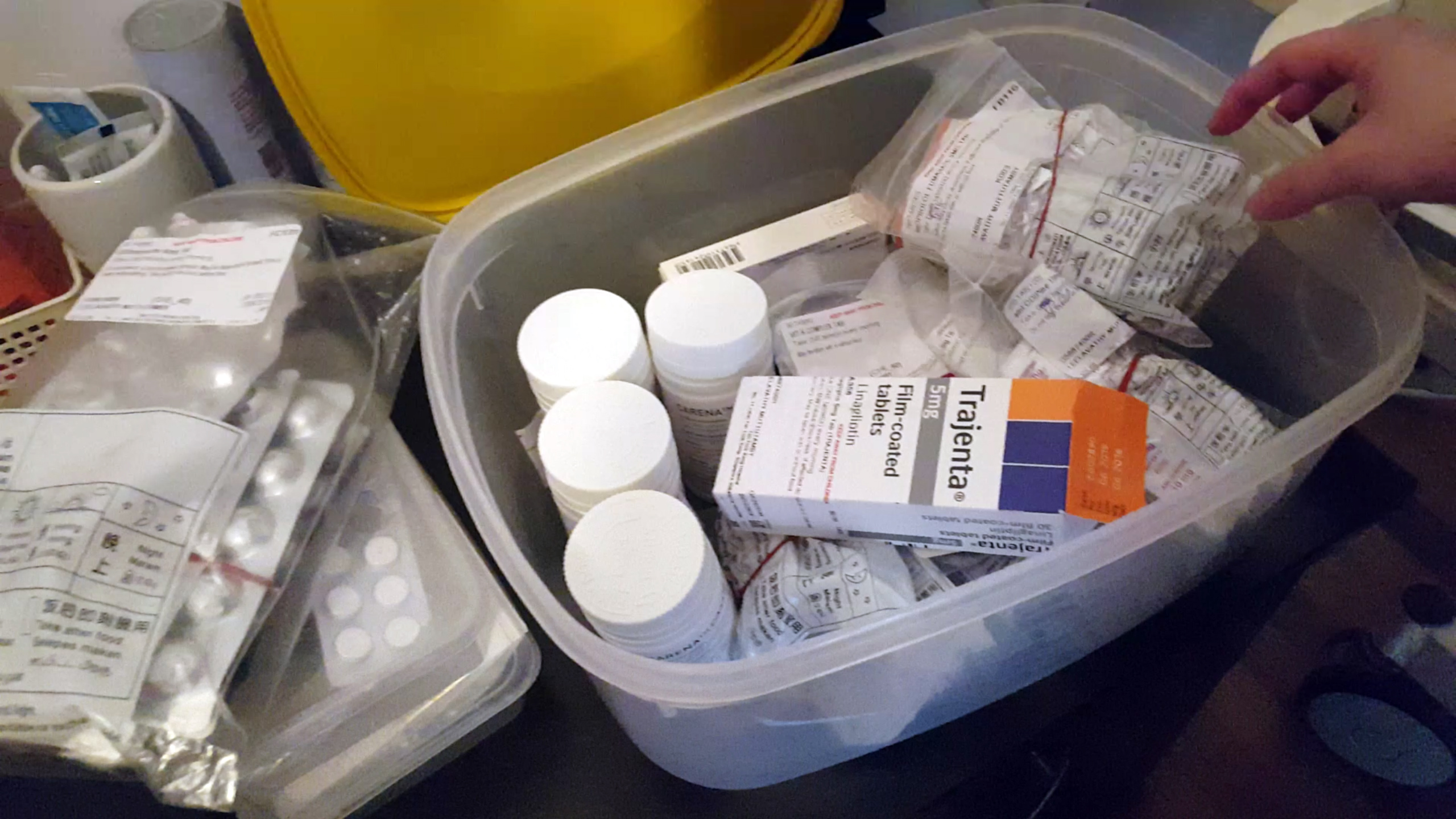

“There was a lot of learning for us. One example was feeding three-hourly on a tube. By the time you finish the one process of changing the patient, turning the patient, getting the milk, feeding her, doing the glucometer or the blood test, giving insulin – it’s time for the next cycle to start,” she added.

“So having a schedule is super important, because any delay shifts the whole schedule, and then for the rest of us… our dinners became (delayed) to 10 o’clock at night, because the priority was ensuring that my mom’s schedule was maintained.”

“There’s a whole host of things to learn for caring for a person who’s bedridden, who has had a stroke”: Mdm Leela’s daughter

The additional costs per month of looking after Mdm Leela come up to about S$2,500, said Kavitha. This is higher than what the family would pay if Mdm Leela were in a six-to-eight bedded community hospital, but she feels it is “all worthwhile”.

The case for home-based care: Care coordinator Catherine Heng, who took charge of Mdm Leela’s case, says home care fills important gaps in the eldercare and step-down care eco-system.

“During my five years in the public sector, I realised that a lot of patients and family members are ushered through the process in the hospital. The patients do get well in the hospital, but subsequently, upon (being) discharged, they are actually very lost and when they get home, they don’t have much of an idea of what is going to be happening at home,” said the former staff nurse in a public hospital.

The 25-year-old added: “There were a few cases which I know of, where they got home, and didn’t continue to manage well, and subsequently were re-admitted for likely the same reasons. It’s quite a vicious cycle for them, and I do realise that there’s this gap in the community. It’s a challenge that home care can definitely fill.”

Given Singapore’s high workforce participation rate, it is unsurprising that Jaga-Me co-founder Julian Koo says 90 per cent of his home care clients hire domestic workers. But he believes the view that home care is expensive is a myth.

“The public healthcare system provides subsidised home care. There are also private options which provide additional support on top of what the public sector can provide,” said the 29-year-old.

Currently, there are various measures to support households which hire domestic workers to care for seniors and family members with moderate to severe disabilities. One example is the Foreign Domestic Worker Grant, which provides a monthly grant of S$120.

Since 2012, this has benefitted at least 10,400 households, with the Government providing a total grant amount of S$20.6 million. Towards the end of 2016, MOH also started piloting an eldercare training scheme for foreign domestic workers, said an MOH spokesperson.

Private home care providers like Jaga-Me offer on-demand home care services, by linking clients to nurses in their vicinity.

Mr Teng: Dementia patient living alone in a rental flat

Not every senior is fortunate enough to have the same level of family support and financial resources as Mdm Leela. But among those with lower levels of support, it is possible to age at home if they are relatively healthy and mobile.

Take retired hawker Mr Teng for example. The eldest of seven children, he has never married and is childless. The 76-year-old is diagnosed with dementia, high blood pressure, and diabetes, and lives alone in a rental flat. He relies on help from his siblings, state-subsidised dementia day care services, and charities like the Tsao Foundation.

Two years ago, Mr Teng’s siblings had a scare when he had a fall and was only discovered some 24 hours later. While mishaps like these might have been easily prevented in a nursing home with round-the-clock care and supervision, Mr Teng is adamant about retaining his independent lifestyle.

“Cost is an issue, and besides, there is no need for it at the moment,” he said. According to his 75-year-old sister, who looks in on him weekly, this reply is characteristic of him as he values his independence, and does not want to burden others.

Mr Teng’s decision is supported by his siblings, with help from the Tsao Foundation’s Community for Successful Ageing (ComSA) Whampoa Centre. Chua Hui Keng, a care manager, took on Mr Teng’s case more than a year ago, and began coordinating services to enable him to live independently.

Mr Teng watching television in his rental flat. (Photo: Linette Lim)

How they made it work: From 8.30am to 4.30pm on weekdays, Mr Teng attends dementia day care at St. Andrew’s Community Hospital, which costs about S$300 to S$400 a month. When the bus drops him off at home, he usually walks to the nearby food centre to buy his dinner, before heading home.

“I watch TV, and talk to people,” said Mr Teng, when asked how he spent his time at day care. This is a marked improvement from the socially withdrawn person he was, according to Ms Chua, who believes that attending dementia day care has had a positive effect on Mr Teng’s social wellbeing.

“He is more open, more alert, and more engaged now. He used to shoo us away, but we’ve managed to build rapport with him,” added the 40-year-old. Outside of dementia day care, Mr Teng’s younger brother pops in to make sure he takes his daily medication, while Ms Chua makes sure there is a weekly cleaning service in place.

Ms Chua’s role in linking Mr Teng to services he needs – from housekeeping, to dementia day care – is known as case management, or care management within the Tsao Foundation. The Foundation, which is widely considered a pioneer in the field, says their “integrated, person-centred medical and psycho-social services” reach thousands of clients.

“We assess the needs of a client using a bio-psycho-social framework. Biologically – what are the things they can do? Can they cook, can they dress themselves? Are they able to see well, do they have fall risk? Psychologically – how are they feeling, do they have somebody to talk to? Do they feel secure? And social – the family and and social support they have,” said Ms Chua.

“We assess the gaps that need to be filled, and come up a care plan. Then we coordinate services, to bring in services to enable these older persons to age in place,” she explained, noting that the overarching idea is to empower the older person as much as possible.

“Instead of giving them the service – taking over basically – we look at their capacity and competency. How much can they do? And we see whether we can maintain that, or improve on that, before we say, ‘hey you can’t do this, let somebody else do it’. Then obviously they would become even more disempowered.”

A patient has his blood pressure checked at the Tsao Foundation’s ComSA clinic in Whampoa. (File photo: Ooi Boon Keong, TODAY)

The case for community-based care: According to MOH, injecting aged care services within public housing estates is a “key thrust” of its efforts. For instance, it has expanded, and will continue to expand day care and home-based care capacity. There are enhanced subsidies for home- and community-based care, and there are also plans to pre-build larger centres called “Active Ageing Hubs” for seniors within new HDB developments which will serve a range of eldercare needs.

All these dovetail with other efforts to build stronger community-based support to complement family support. For example, the Government announced in this year’s Budget that it will pilot a Community Networks for Seniors initiative, which aims to link up befrienders, volunteers, and Voluntary Welfare Organisations (VWO) with the elderly in their estates.

When implemented successful, this will replicate on a larger scale, what charities and VWOs such as the Tsao Foundation and the Thye Hua Kwan Moral Society have been doing in certain neighbourhoods.

But what worries social workers like Ms Chua is a lack of awareness and understanding on the part of caregivers and elderly dependents. “We serve more of those living in rental flats, but we also see three-roomers, four-roomers, who are defined as more well-resourced. Even these people have just as limited an understanding of how the whole system works, of what is out there.”

This limited understanding, especially of the alternatives to institutional care, means elderly persons may get moved along a process chain with little consideration for what they want, said Ms Chua, echoing former public sector nurse Ms Heng.

“Singaporeans are very efficient – once there’s a problem, (you look for a) solution and options. But in between, how do you get to the solution, what is the thinking behind it? A lot of times, when we look into housing the elderly, we look at the solutions very quickly but we don’t look at the process,” said Ms Chua, adding that it would help if caregivers have truly considered and exhausted alternative care arrangements.

She admits that whether this happens or not depends greatly on individual and family circumstances. Ideally, the caregivers have to initiate honest conversations with their elderly dependents, and the elderly have to want to be engaged.

“You have to have tried. This helps the older person cope because they would know the children have tried. This also helps the children or caregivers because otherwise they may also be suffering psychologically, from guilt.”

This is the second of a two-part series on ageing in Singapore. The second installment looks at daycare and home care options, while the first focused on institutional care options.