Study using bacteria-infected male mozzies to render females sterile to be held in three areas From October, some residents might notice more mosquitoes buzzing in their neighbourhoods.

But don’t worry, they won’t bite. In fact, these male Aedes mosquitoes do not transmit disease, but are Singapore’s latest allies in the fight against dengue.

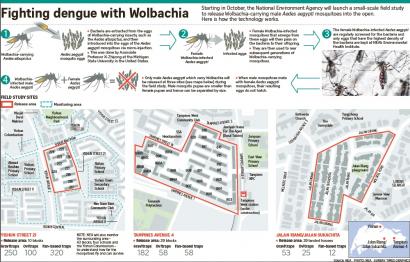

What the male mosquitoes will be armed with is Wolbachia, a naturally occurring bacterium. When these males mate with female mosquitoes, the bacterium causes the females to lay eggs that do not hatch.

Over time, this could lead to a fall in the population of Aedes aegypti mosquitoes, which transmit the viruses that cause dengue fever.

These mosquitoes also carry the chikungunya and Zika viruses. Yesterday, Environment and Water Resources Minister Masagos Zulkifli announced that the National Environment Agency (NEA) will release the bacteria-carrying mosquitoes at three sites as part of a field study.

The areas, Yishun Street 21, Tampines Avenue 4 and Jalan Riang/Jalan Sukachita in Braddell Heights, previously had dengue outbreaks and represent a cross-section of typical housing estates here – both high-rise and landed.

The Environmental Health Institute, a public health laboratory at the NEA, has been studying this novel method since 2012 and carrying out risk assessment and research to confirm that it is safe.

Mr Masagos told reporters that while efforts to reduce the mosquito population have been “fairly successful”, Singapore is still susceptible to dengue outbreaks as it is in a region where dengue is endemic.

He said the new method “works together with source eradication”.

“Whatever we’re doing today to ensure that mosquitoes don’t have opportunity to breed must continue.”

The NEA estimated that an average of one to three male mosquitoes per person will be released at regular intervals at each of the three sites.

The six-month field study aims to understand the behaviour of Wolbachia-carrying Aedes aegypti male mosquitoes in the urban environment, such as how far and high they fly, and how well they compete with counterparts without Wolbachia to mate with females.

To collect data, NEA will set up traps at locations including public spaces and the homes of resident volunteers.

The data will support the planning for a suppression trial, which may start next year.

Experts said that similar trials abroad have had a positive impact.

For instance, a release of Wolbachia-infected mosquitoes led to a more than 90 per cent drop in the mosquito population on an island in Guangzhou, China, under a pilot project starting in March last year.

Professor Ary Hoffmann from the University of Melbourne, who sits on the Dengue Expert Advisory Panel appointed by NEA in 2014, said: “Sterile release has been used against disease vectors and agricultural pests very successfully for many years around the world.

“The only difference here is that sterility is being generated through Wolbachia rather than radiation, but Wolbachia bacteria are already present in many insects…and do not pose any risk to humans.”

He added that Wolbachia, which can be found in over 60 per cent of insect species including butterflies and dragonflies, cannot be transmitted to mammals, including humans, as the bacteria cannot survive outside insect cells. Mr Derek Ho, director-general of NEA’s Environmental Public Health Division, said residents should continue mosquito-control procedures, such as clearing stagnant water.

Associate Professor Vernon Lee, of the National University of Singapore’s Saw Swee Hock School of Public Health, said: “Any gains through the Wolbachia method could be negated if residents provide mosquitoes with an abundance of breeding sites.”

Housewife Winnie Lim, 49, who lives at one of the Tampines blocks where the field study will be conducted, said the Wolbachia technology sounds like a “good idea”.

“Instead of fumigating all the time, this is a long-term effort to wipe out the mosquitoes.”

ateng@sph.com.sg