Follow our new CNA LIFESTYLE page on Facebook for more trending stories and videos

SINGAPORE: These days, Chinatown has become synonymous with two things: Hordes of tourists who soak in the sights at Temple and Pagoda Streets, or bar-hoppers on their way to that hip, new F&B outlet.

But for three Singaporeans who grew up there decades ago, Chinatown was way more than a tourist trap or a nightlife destination. It was a dirty, dodgy and sometimes even dangerous place to live in. But theirs was a childhood to remember. Here are their stories.

YIP YEW CHONG: ‘THE CORPSE WAS SITTING UP!’

It’s one of the most macabre childhoods one could ever have: From the moment he was born until he was teenager, Yip Yew Chong spent his time around dead people.

Mural artist Yip Yew Chong standing exactly where his house used to be along Sago Lane. It’s now a car park. (Photo: Mayo Martin)

The 49-year-old accountant-artist, who’s known for his Instagram-friendly nostalgic murals in places such as Tiong Bahru and Kampong Glam, lived with his family at the infamous Sago Lane, also known as the Street of the Dead.

Today, it is nothing more than a busy carpark right beside the Buddha Tooth Relic Temple, and just across the road from Maxwell Food Centre and a short walking distance from the busy nightlife area of Erskine Road and Ann Siang Hill. But during the 1970s and 1980s, his family lived on the second floor of a shophouse smack in the middle of action.

“In the day, there were funerals, and at night, there would be wakes. When I went downstairs, I’d have to walk past funeral parlours and the corpses would be on wooden planks. After a few days, they’d wash the corpses out in the open before putting them inside coffins. Nothing in those days was sanitary but you get used to it!” recalled Yip, with a laugh.

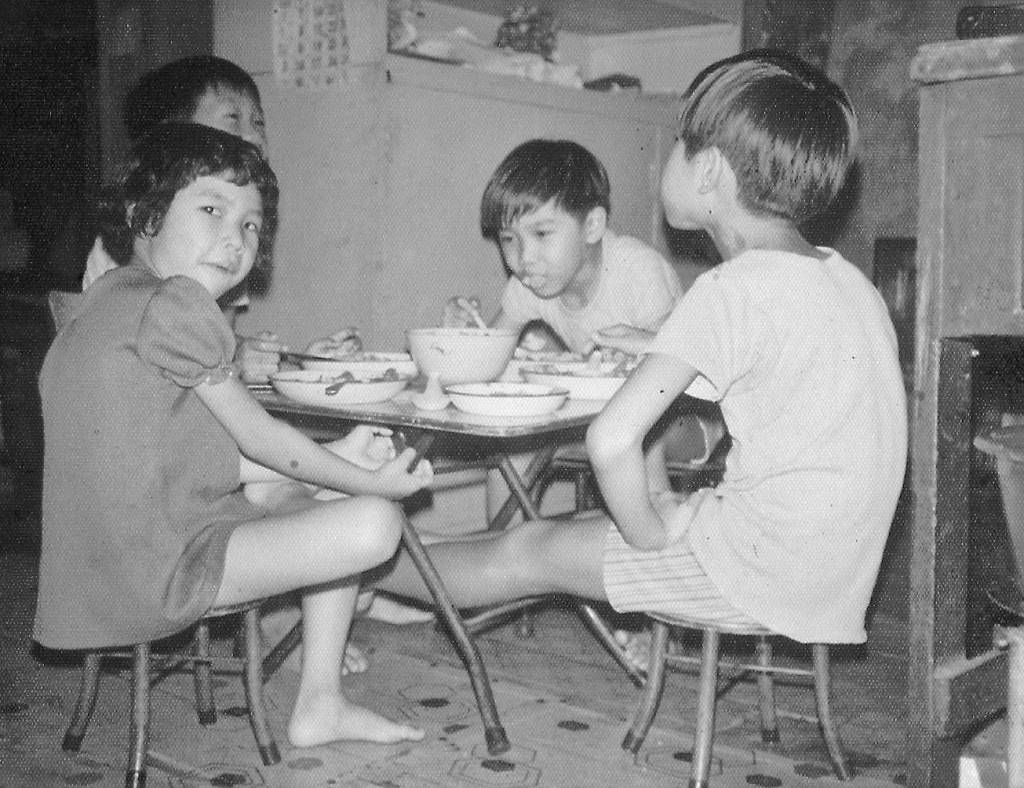

Yip Yew Chong (centre) as a child living on the second floor of a shophouse along Sago Lane. (Photo: Yip Yew Chong)

His family was literally surrounded by things related to death. The store below them sold paper effigies and nearby were a couple of funeral parlours. Opposite the street (where the temple now stands) were shops that made mourning clothes and coffins.

From his second-floor vantage point, Yip had a bird’s eye view of everything. “It became very interesting at night. There would be rows of tables out on the streets during the wakes and at 10pm, the rituals would start. A priest would spit kerosene into a small bonfire, which would result in a fireball directly underneath our house – every other night,” Yip said, adding that he had to put up with the noise, too.

Artist Yip Yew Chong’s drawing of his childhood memories of Sago Lane. (Photo: Yip Yew Chong)

“I remember studying for PSLE and it would be tung-tung-chang-tung-tung-chang all day and night!”

During the day, the street was just as lively as huge, colourful paper effigies would be displayed along the street, and trishaws bearing tourists would often stop by to take pictures.

As a young boy, Yip also heard of some unusual stories.

“Once, there was an ambulance that came (to deliver a corpse) and when the door was opened, there was a commotion because the corpse was sitting up!” he laughed. “Maybe the muscles had contracted or something but people were talking about it for weeks.”

Another incident involved the police dropping by during the last few days of a wake. The corpse had already been in the coffin for a week and the police, who was investigating an incident, demanded it be opened.

“By the time you put a body inside a coffin, it already smells – and when they opened it, wah, the whole street stank!”

One of the death houses along Sago Lane in 1960. (Photo: National Archives of Singapore, Wong Ken Foo)

In 1983, a 14-year-old Yip and his family had to move as the shophouses was slated for demolition as part of the government’s plan to clean up the Singapore River – the source of all the rubbish in Chinatown.

Together with the other residents and hawkers along Sago Lane, they moved to nearby Chinatown Complex.

“But the strange thing was, after the street was demolished, the place was a grass patch for many years and we could see it from our new home,” said Yip, adding that the empty land would become the site of operas and temporary market stalls.

Ironically, when his father died in 2009, the family set up the wake on that very same patch where Sago Lane once stood.

Yip Yew Chong’s old home along Sago Lane. It’s the one with the clothes hanging outside to the far left. (Photo: Yip Yew Chong)

Despite having created murals of old Singapore all around the city (including a recent one at Chinatown Complex), Yip hasn’t done anything related to Sago Lane due to the taboo surrounding death.

But he hasn’t forgotten it. One of his very first murals included an image of an amah (a domestic helper/nanny), the same woman who had lived with his family as a fellow boarder on 9A Sago Lane.

VICTOR YUE: ‘MY UNCLE WAS ONCE BEATEN UP’

If you thought your childhood was tough, try telling that to Victor Yue, who grew up in Chinatown with no proper toilets, and always having to keep an eye out for gangsters.

Retiree Victor Yue visiting his old childhood haunt in Craig Road. (Photo: Mayo Martin)

“A lot of the streets were gangster-infested. Different gangs had different turfs and when you’re around 10 years old, you have to be careful not to step into another’s turf, you know?” said the 65-year-old retired engineer and heritage enthusiast.

His elders would also warn him to be alert when passing by coffeeshops. “In those days, they’d say you better be careful – when cups get overturned, you run for your life. It’s a sign of a fight!”

Yue has lived in different parts of Chinatown all his life and spent his first 10 years at 29 Craig Road. Today, the row of shophouses where he lived has made way for Craig Place condominium, where foodies drop by today for the Spanish tapas twin restaurants Binomio and El Tardeo.

A coffeeshop at Craig Road in 1984. If cups get overturned, it’s a sign of a fight, said Victor Yue. (Photo: National Archives of Singapore)

But Yue’s vivid memories of the area as a kid during the 1950s and 1960s was different. His family rented a room on the upper floor of a Peranakan woman’s shophouse – which proved tricky considering the row of houses on the street had no sewage system and relied on nightsoil carriers.

“It stank and sometimes, if you go and s**t at the wrong time, you can find that the bucket has disappeared because the guy came to change it,” said Yue. “And since we were on the second floor, you always prayed that when the guy walked up the flight of stairs, he didn’t spill!”

Nevertheless, Craig Road had enough to entertain inquisitive youngsters like Yue, who would wander around the area up to Duxton Road, which today is packed with bars and restaurants. Back then, there was a small temple on the second floor of one of the shophouses, which was popular among residents. (Further up on Duxton Hill, where you’ve now got L’Entrecote The Steak & Fries Bistro and Lucha Loco, was no man’s land for kids like Yue, who wouldn’t dare enter another gang’s turf.)

A scene of Craig Road in 1984. (Photo: National Archives of Singapore)

Yue’s immediate vicinity was equally interesting. He recalled that at the corner of Craig Road and Neil Road was a Tiger Balm factory, while opposite it was an old building where Chinatown Plaza now stands. “There were jambu and mango trees outside and we kids used to wait for the fruits to drop,” he said.

There were also a couple of interesting shops along the road, selling wooden swords for wushu practitioners and a rental stall for old Chinese comics. At one corner, the results of chap ji ki – an old illegal lottery – would also be written out and sometimes his grandmother would ask him to check out the results.

The shophouse where Victor Yue lived as a kid along Craig Road is long gone. In its place today is a condominium. (Photo: Mayo Martin)

Incidentally, there were also two spirit mediums along the street – including an old lady who lived in a shophouse just beside where Pasta Brava now stands. “She’d be cooking and someone would come for consultation. She’d stop cooking, go into a trance, give you advice, then go back to cooking. She was a spirit medium on-demand,” he quipped.

The street’s colourful character was also literally found on the pavement and walls – Craig Road was in the late Lee Kuan Yew’s Tanjong Pagar constituency. But Yue remembers there used to be an office of the opposition group Barisan Sosialis somewhere.

For a child, these were all adult stuff – but one thing he had to really be alert about were gangsters. Yue would remember sneaking to the nearby Yan Kit Swimming Complex for a dip – but he knew he was taking risks.

Craig Road was a colourful place before, with political parties putting up posters everywhere, a shop that sold wooden swords and even two spirit mediums (including one “on-demand”). (Photo: Mayo Martin)

“A young boy might come up to challenge you by asking: ‘What number do you play?’ which referred to gang numbers,” he said. “If you quoted the wrong one, you’d be in trouble. If you thought you could bully him, you’d better watch out because behind him, there might be a bigger guy watching.”

Luckily, Yue never had any personal encounters by making sure he didn’t stray far from home (gangs never harmed those who lived in in their turf, he pointed out). But there was one incident when he was very young that proved too close for comfort.

“My uncle was once beaten up through mistaken identity. We had to seek help from the elders to find out, and later the gang apologised. In those days, the gangsters or secret societies had a code of conduct, so apologies were very ritualistic. They had to give you candles and things to pray to your ancestors and gods as a form of a very formal apology.”

CHARMAINE LEUNG: ‘SOME MIGHT SHOW A LITTLE BIT OF FLESH’

Her mother ran a brothel. Her nanny was an alcoholic. And she once lived in fear of her friends discovering her home was in a red light district. Charmaine Leung’s childhood story is a Channel 8 drama waiting to happen.

Author Charmaine Leung grew up in 15A Keong Saik Road, the shophouse in the middle, flanked by her mother’s old brothel and the temple where they would hang out and watch the world go by. (Photo: Mayo Martin)

At the moment, though, you can already read all about it in her memoir titled 17A Keong Saik Road. The 45-year-old author’s moving story about growing up in the area during the 1970s was published last year. The title’s address refers to her mother’s brothel, while Leung herself lived on the second floor of the shophouse next door 15A with her nanny.

Today, 17A is a hip bar and restaurant called Sluviche, while 15A is the office of German radio and television outfit ARD.

But some places have remained the same. Next door is the Cundhi Gong Temple, where Leung and her mother would often sit down to watch their unusual world go by. Just opposite the road is a brothel that still operates today, marked by a light box with the number 8.

Charmaine Leung as a child living in 15A Keong Saik Road, right beside her mother’s brothel. (Photo: Charmaine Leung)

“We’d sit around 6pm or 7pm and our view would be the ladies from that place who would come out and burn incense for good business,” she recalled.

As a young child, she would often see them as they walked to and from the brothels. “They’d wear nice dresses in pretty hot weather,” said Leung. “And they weren’t what ordinary people would wear.”

“Some might show a little bit of flesh. But the dresses seemed more like what people would wear when going onstage to perform, or what a nice dress would be in the 1970s and 1980s but exaggerated. Their skirts would have a bit of the can-can feel but shorter.”

In the past, brothels were discreetly advertised by white lightboxes with numbers in red. There are still a few remnants of these along Keong Saik Road. (Photo: Mayo Martin)

Back then, her mother’s brothel was just one of the many along Keong Saik Road and nearby streets. “At any one time, you can get up to 40 to 50 of these. Every few houses, you’d see the white box with the red words and numbers. “19” was one of the bigger ones with quite a lot of pretty, younger ladies,” she said, adding that prostitutes would start coming in at around mid-afternoon and the whole area would be the busiest between 8pm and 10pm.

Of course, at that age, she was more or less oblivious to everything. “Overall, it never felt too dodgy because there were no transactions on the streets. But my perspective is really that of a child,” she said.

But life in Keong Saik Road wasn’t just all about the brothels. Leung remembers loving the feeling of the street in the mornings.

“There was almost no life compared to at night when it was a lot buzzier. There was a sense of serenity. Outsiders didn’t really dare to come in, so it almost felt like a city waking up,” she said.

Keong Saik Road in 1989. (Photo: National Archives of Singapore)

Leung also remembers playing along the back alleys and visiting her neighbours at nearby Jiak Chuan and Teck Lim Roads. Most of them are gone now, replaced by hip F&B places, but Leung remembers them vividly: Lime House and Harry’s Bar used to house a refrigerator repair store and a paper box shop, respectively. The back half of Spanish bar Esquina, she pointed out, was where her favourite ice cream uncle used to be.

“It was just home-made ice cream with flavours like red bean, durian, corn and attap chee, which was my favourite,” she said.

Gentrification has undoubtedly changed the face of Keong Saik Road, and Leung has mixed thoughts about it. While she welcomes the preservation of architecture and how some businesses embrace the place’s history (Keong Saik Bakery has done buns inspired by the shophouse’s previous majie owner), she bemoans the absence of actual residents who can form a community.

“It has become a place where people visit, consume and walk away. And sometimes, I feel everything’s a bit too bright – the place used to look more lived in,” she said.

A photo taken in 1989 of Jiak Chuan Road, which is perpendicular to Keong Saik Road and right in front of where author Charmaine Leung used to live. (Photo: National Archives of Singapore)

Since coming back from Hong Kong, where she had been based, Leung has been active in promoting the area’s heritage. Aside from the occasional tours, she was also involved in the Chinatown segment of the recent Singapore Heritage Festival. She’s also been helping to promote theatre group Drama Box’s upcoming show in June titled Chinatown Crossings, which looks at the hidden histories of the area.

In a way, all these is a continuation of her book, which was an effort not just to tell her story but that of an overlooked community.

“It was also about people who, no matter what happened or how hard lives were, made the best of what they had. These are the stories of the early immigrants, of people who laid down the foundations for Singapore. Without these people, we probably wouldn’t have what we have today.”