SINGAPORE: The halls are dark and the viewing gallery silent, but in the blue of the Open Ocean Habitat, the rays are in a fever, unconcerned that the crowds and flashing cameras are currently not part of their daily routine.

Stingrays the size of dinner tables crowd around aquarist Wendy Yam. Smaller cownose rays nuzzle her hopefully as she hand-feeds them fish and squid from a tub full of sashimi-grade seafood.

On a normal day, the smushed faces of children and a thicket of selfie sticks would line the tank’s glass panel, but today, one camera – a video journalist’s – captures the feeding frenzy.

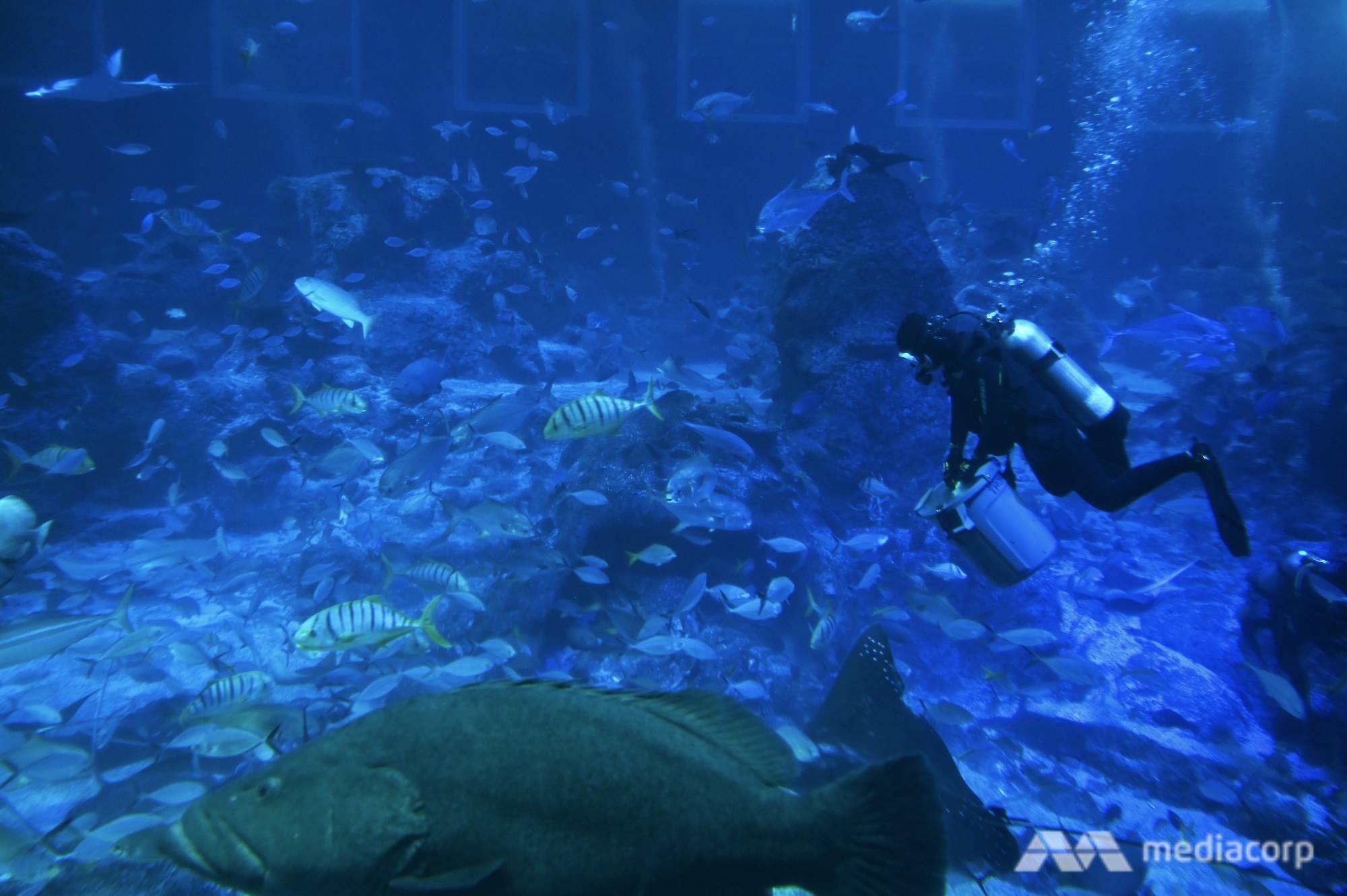

In the midst of Singapore’s “circuit breaker”, the SEA Aquarium at Resorts World Sentosa has been closed to the public since Apr 7, but aquarists such as Wendy are still working and diving. They’re not your typical essential worker, but to the marine creatures, they’re indispensable.

Aquarist Wendy Yam during a dive feed in the Open Ocean Habitat at the SEA Aquarium on May 20, 2020. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

“Sometimes when we dive in the exhibits and you look through the acrylic panels it looks quite sad and it’s very quiet (as) you don’t have guests waving at you or asking you to take pictures,” Wendy mused.

“One thing that I miss are the kids … they get very fascinated when they see the animals. When they see the divers they get even more excited.”

But with no guest engagements, the aquarists are spending more time and energy on the marine animals.

“We get to spend more time with the animals, get a little more personal with them,” Wendy said, who reeled off anecdotes about the animals and shared their quirks in spontaneous bursts throughout the day that CNA spent with her.

Aquarist Wendy Yam feeding porcupine fish at one of the exhibits in the SEA Aquarium. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

The tasselled wobbegong shark pups wag their tails whenever they see food coming their way. The divers all need to wear hoods because the curious bowmouth guitar shark might, when the mood strikes, nibble at their heads. The bonnethead sharks – which look like miniature hammerheads – are smaller and are target-fed using a stick to make sure they get their share.

“During our dive feeds, because it is no longer a show feeding, we can target some of the smaller rays that are at the bottom of the exhibit,” she said. “Maybe they get so-called bullied by some of the larger rays, so we spend more time feeding them to ensure that all of them get food.”

FISH ARE FRIENDS, AND FOOD

Aquarist Wendy Yam (right-most) preparing food for the marine animals on May 20, 2020. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

The evening feed comes near the end of a full day that started at 8am when Wendy and her team diced and minced seafood in the kitchen for the over 100,000 creatures in the aquarium.

They sneak in some goodies as well – vitamin powder and garlic – which help boost their immunity.

“It makes our fish stronger,” the 26-year-old yelled over the steady drumbeat of chopping cleavers and slippery slop of fish bits being portioned out for the different species.

400kg of seafood is prepared each day to be fed to the more than 100,000 marine creatures at SEA Aquarium. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

In an hour or so, trundling carts carrying about 400kg of feed are pushed out – yes, that’s just for one day. Then it’s off the feed the fish.

Some of the food is scattered from the surface, and some is used for the dive feeds, but the three reef manta rays in the Open Ocean Habitat get a special meal in the morning.

When Mako, Mika and Manja hear the sharp pop of the feeding scoop hit the water surface, they know it’s time for breakfast krill.

Reef manta rays at the SEA Aquarium are fed krill every morning. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

Circling the tank, they swooped in with their maws wide open and scooped up the tiny, pink shrimp – fortified with vitamins and minerals.

Post-feed, Mika spread her wings, slapping the water playfully in a little dance in front of the aquarists.

“IT’S LIKE VACUUMING YOUR HOUSE”

Cleaning the largest tank in the aquarium – which holds more than 42 million litres of water (equivalent to 17 Olympic sized swimming pools) – is like vacuuming your house, Wendy says.

I couldn’t just take her word for it, so this journalist, who shadowed her for most of the day (at a safe distance, of course), gave vacuuming a giant fish tank a go.

Aquarist Wendy Yam uses a siphoning bell to vacuum the Open Ocean Habitat at the SEA Aquarium. (Photo: Chew Hui Min)

When you vacuum your house, there’s no need to strap an air supply to your back, don a wetsuit and fins, and dive to the bottom of a 12m-deep tank. Once we reached the bottom, hoses hidden in the rocks were unrolled and siphoning bells attached to them.

Moving methodically, divers placed the siphoning bells flush against the floor of the tank, “vacuuming” the substrate, which is made up of broken coral and sand.

The suction stirs up the sand, which settles to the bottom again after the dirt, which floats up, is sucked from it. That goes through a biofilter and into the water system, before the cleaned water is pumped back to the tank.

In an hour, two divers went through a section of the tank about the size of a studio apartment. Then they needed to take a surface interval before the next dive, to avoid getting decompression sickness.

The siphoning hoses are coiled and hidden behind rocks in the aquarium. (Photo: Chew Hui Min)

It takes 10 hours of diving to complete the Open Ocean Habitat, so rather than vaccuming a house, it is more like vacuuming 10 small houses, over a week or so.

Besides keeping the substrate clean, the aquarists sometimes mop the acrylic panels to keep them clear of algae. We circled the tank, observing the marine animals to check their condition.

Wendy peeped into the nooks and crannies, pointing out to me a bamboo shark sleeping under a coral. As we swam, eagle rays swept past, tuna swooshed by in silvery streaks, and a curious batfish pecked at my fingers.

Aquarist Wendy Yam holds up a “mermaid’s purse” or shark egg case. These are usually unfertilised. (Photo: Chew Hui Min)

“It’s a good time for the divers to go down and get a more up-close view of the animals to see if they’re sick or if they’re healthy – whether they have any health issues, whether they are pregnant,” said Wendy.

“We might notice that maybe one of them is swimming a little slower – these are things we have to flag.”

Before returning to land, we paused in the shallows to watch Mako, Mika and Manja glide and swoop through the tank.

“WHEN YOU’RE WORKING YOU DON’T FEEL TIRED”

After shadowing Wendy for most of the day, and doing just one dive, this journalist was exhausted but Wendy looked as sprightly as she did in the morning.

“When you’re working you don’t feel tired,” she said. “(But) I can go home and eat dinner and just fall asleep after that.”

Wendy Yam, 26, an aquarist at the SEA Aquarium. (Photo: Marcus Ramos)

It’s a physically demanding job, and the pint-sized Wendy straps on up to 15kg of gear each time she dives – about one-third of her weight. The aquarists can do from two to four dives a day, she said.

It’s also a job where you start the day as a sashimi chef, double up as underwater housekeeper while being responsible for more than 1,000 species with different needs, diets and habitats.

But it’s these creatures that keep her going, she said.

“I used to think that fish were just fish … but actually they each have their own character,” she said.

“Like our different rays – maybe black blotch rays would tend to be more docile – they tend to just rest at your feet, whereas leopard rays, during feeding, they are the ones that get more excited they’re climbing all over you.

“Maybe it’s just me, but that’s one thing that I really like, working with them and learning something new every day from them.”