What can the dying teach the living? Quite a bit, it seems.

A small but growing number of people spend their last days recording their thoughts on life and how they cope with impending death in order to share them with others.

They hope to get people thinking and talking about death early enough to re-examine their priorities in life, and take action on matters such as making wills or signing advance medical directives.

Mr Stephen Giam, 51, for instance, had advanced bile duct cancer. He died three weeks ago.

But before his death on Sept 26, he spent five of his last 20 days filming short videos of himself tackling various topics from his hospital bed. Titled “Stephen Says”, the series of 19 YouTube videos covers issues such as: What’s it like to have cancer? How do you make death your “slave”? How do you leave a legacy?

During his life, Mr Giam was a motivational coach. He told his doctors that perhaps being a “death coach” would be useful for others.

“People are afraid, but they also want to learn from you. They are curious: what is it like to be dying?” he said in one of his videos.

The videos have since garnered about 70,000 views.

Mr Giam is not alone in his quest to use his dying moments to reduce the stigma associated with death. Industry observers say they see more of such projects nowadays because of a maturing consciousness among people who want to explore what it means to die well, and the availability of online platforms to get the discussion going.

“Our country is at a juncture where people are starting to question whether we should focus on curative treatment to extend life at all costs or whether it is about quality of life and minimising suffering,” said Mr Mark Lin, deputy director of the charity Monfort Care which started a project called “Good Death” in April.

Mr Lee Poh Wah, chief executive of Lien Foundation, said: “In our various projects involving the terminally ill, we were never short of people who wanted to speak up and tell their stories.

“But perhaps the greater appeal now stems from the fact that the dying know that they have direct access to a much larger audience in our increasingly connected, online world.”

The Good Death initiative, led by Mr Lin, has a “Last Interview” segment where those who are terminally-ill consent to allow their last few verbal exchanges with their social workers to be recorded and released via videos on Facebook and on a website.

“Benny”, for instance, had pancreatic cancer. In the interview, he said his biggest regret was to divorce his wife and the most important thing he learnt, after knowing that he had little time left, was to treasure his family.

Another video showed the dilemma that “Mr Tan”, who had oesophageal cancer, faced when he had to decide whether or not to opt for a high-risk operation that would extend his life for a while.

Both Benny and Mr Tan have since died and their videos were uploaded online a few weeks ago.

Lien Foundation and the Asia Pacific Hospice Palliative Care Network also released a documentary called “Life Asked Death” about a week ago.

The 26-minute online film showed the challenges and triumphs of bringing palliative care to different parts of Asia, through interviews done with people who were dying and who were in pain due to a lack of pain medication.

Beyond the online space, other projects, such as “Before I Die”, venture into the community to engage heartlanders on the issue.

The people who were willing to publicly share the very personal journey of facing death do so for various reasons.

For Mr Giam, it is not only about helping others learn from his experience, but also a therapeutic process for him to talk through how he was feeling.

His last words on the video were: “I hope the videos are interesting and meaningful to you because these are the things I am also struggling and working on on a daily basis now.”

Although death remains a taboo topic for many, the dying hope their videos will get these important conversations going long after they die.

Said Dr Jamie Zhou, an associate consultant in the division of palliative care at the National University Cancer Institute, who helped edit Mr Giam’s videos: “Nothing is more powerful than a patient’s perspective and Stephen kept it real by being authentic and vulnerable. He believed very strongly in what he was doing.”

Promises to keep; miles to go before I sleep

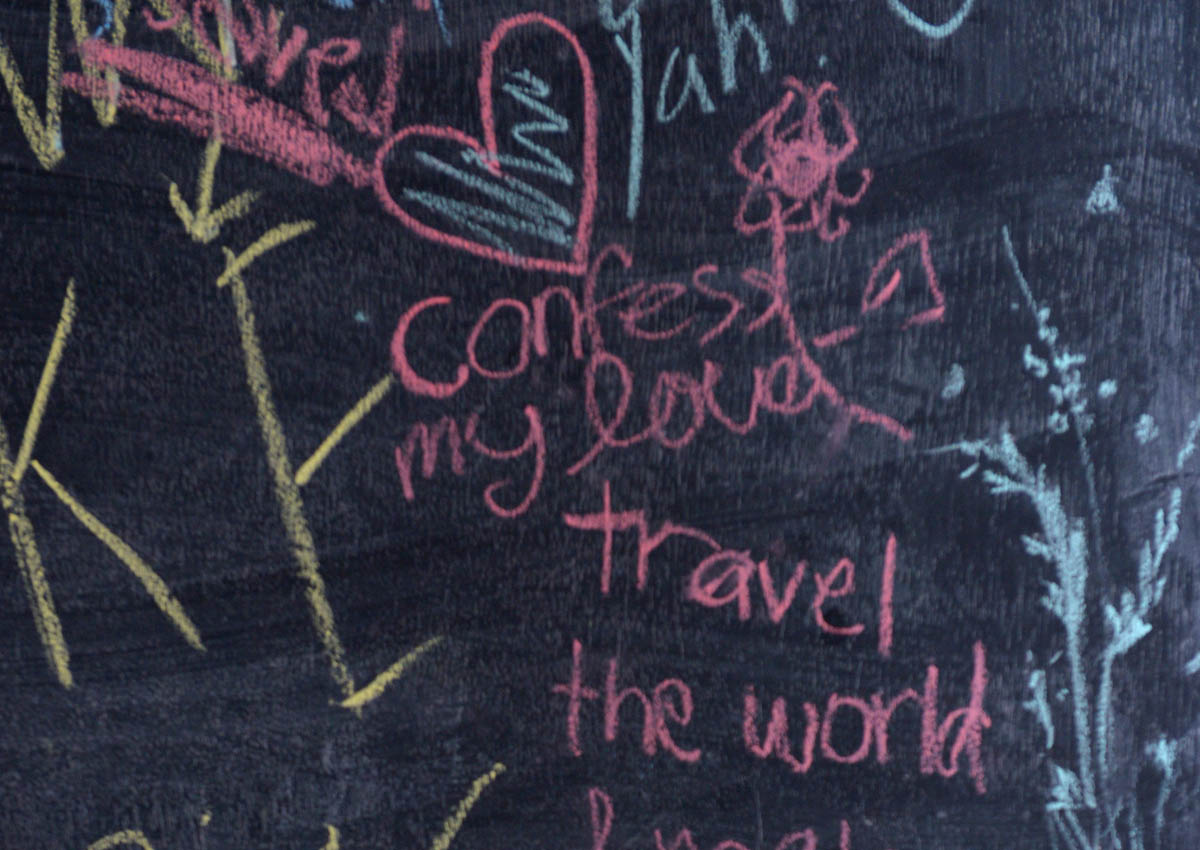

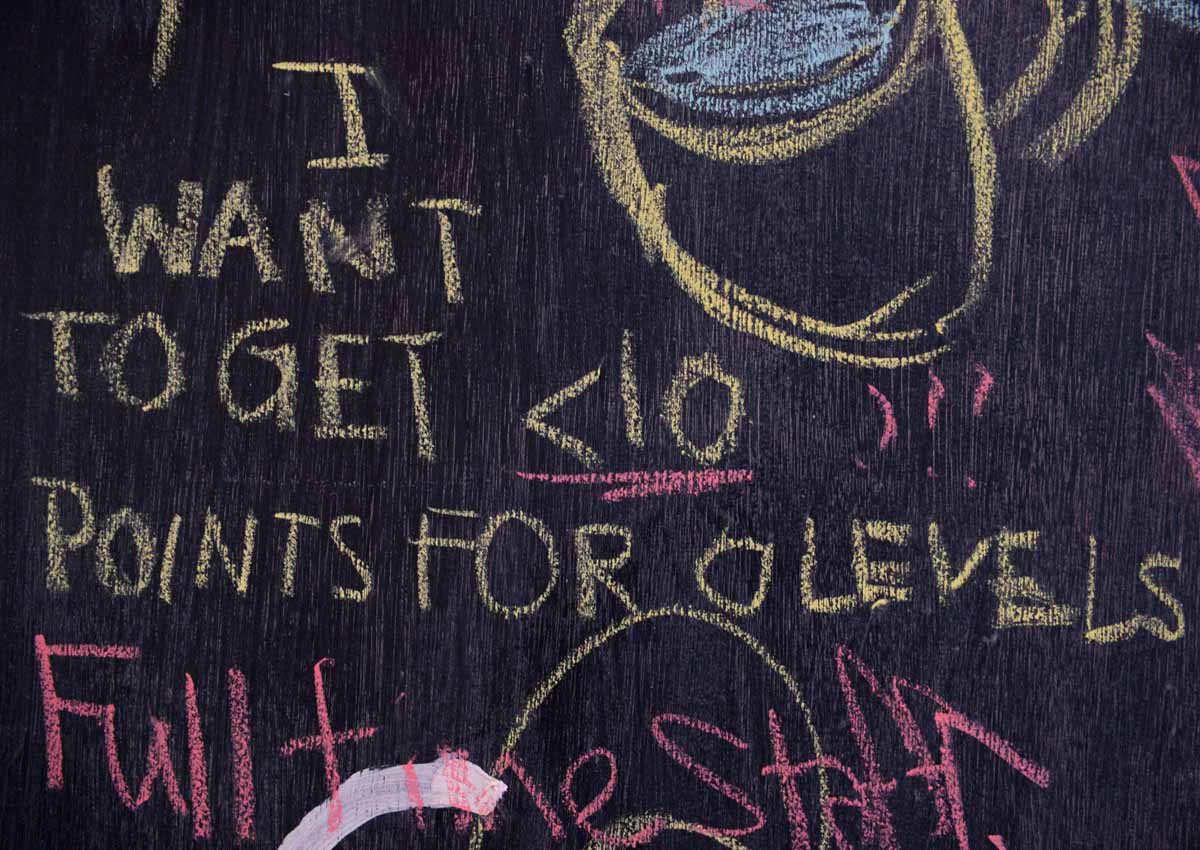

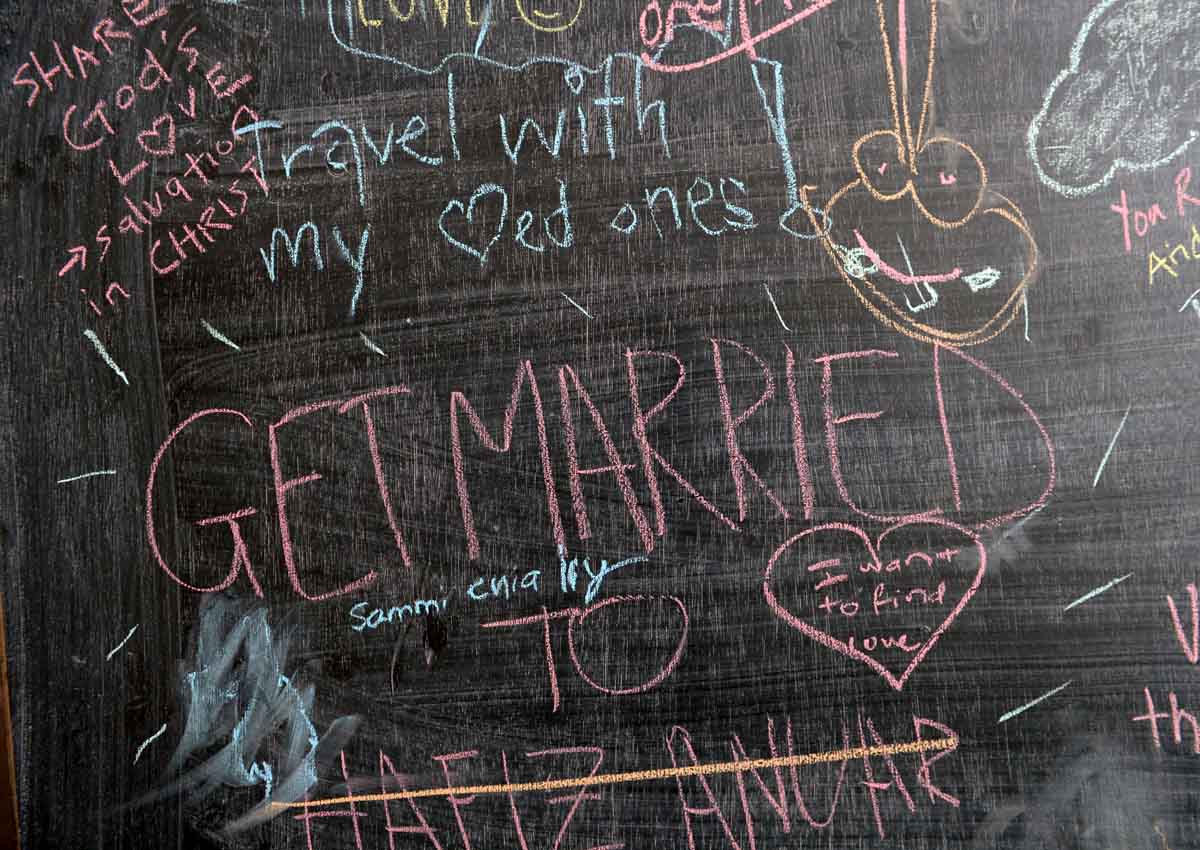

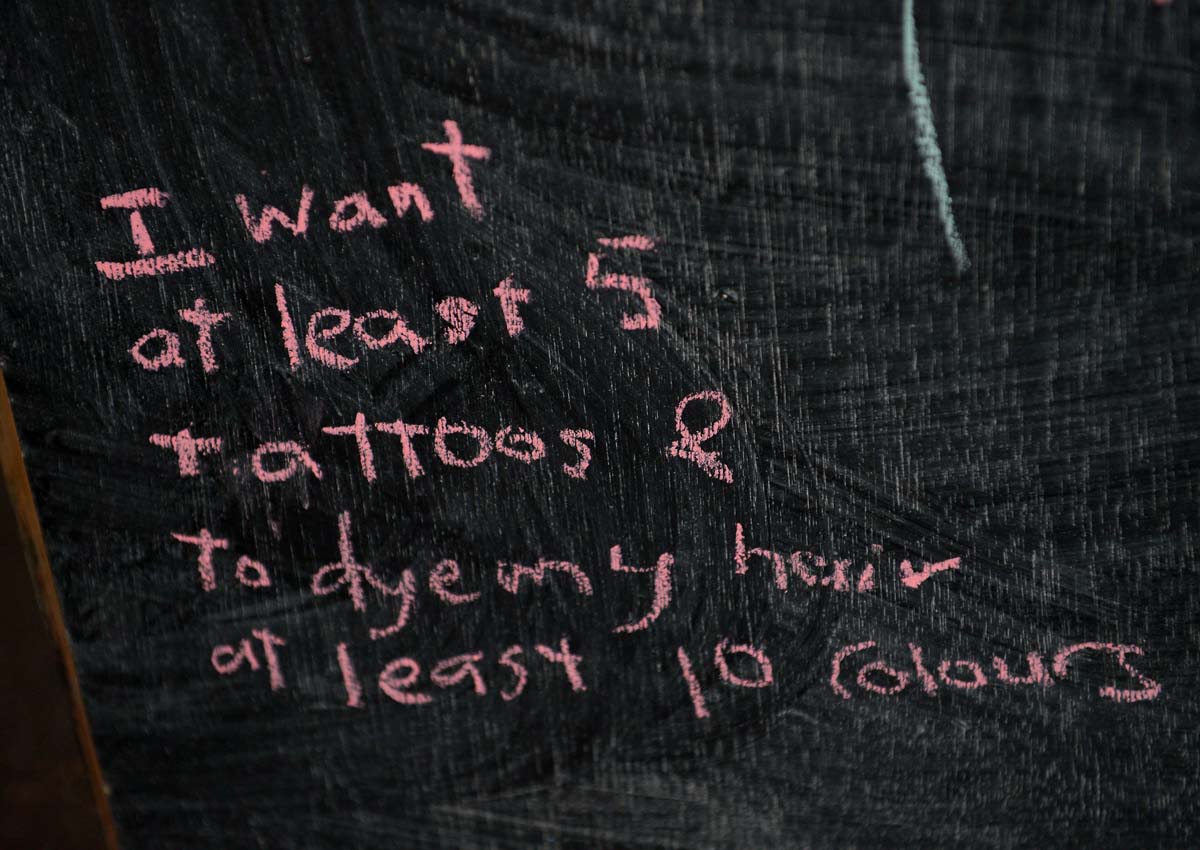

From seeing the Northern Lights to writing a book, many Singaporeans have laid down their plans for the things they want to do during their lifetimes.

Before I Die, a global art project, was brought here last year by a group of National University of Singapore medical and nursing students last year, including Jonas Ho and Zachus Tan, both 21.

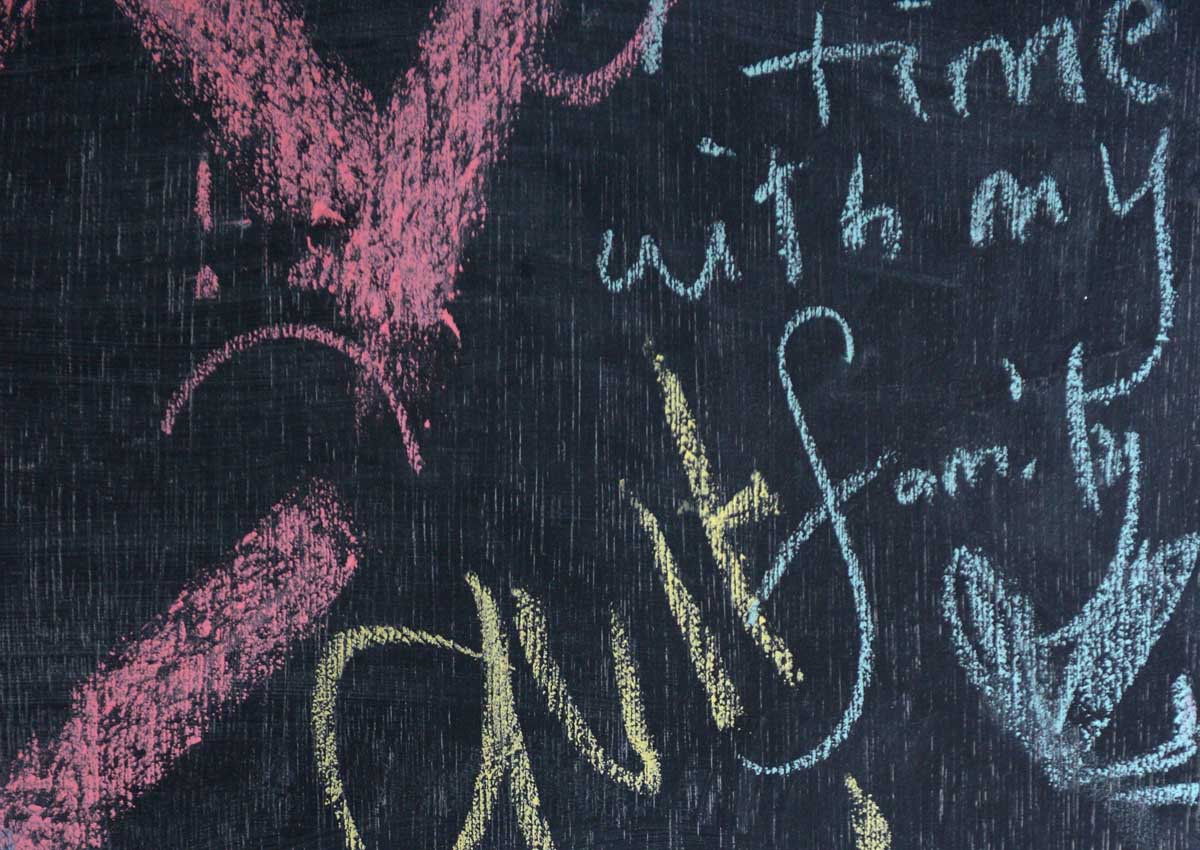

Chalkboards with the tagline Before I Die: My Last Year are being set up in shopping centres, hospitals and universities this month for people to put down their thoughts on what they wish to do.

For some, it is just spending time with family and friends, finding peace within themselves and catching the sunrise and sunset every day. Others plan to use up all the money in their bank account.

For more information, visit the Before I Die Sg page on Facebook.

Getting some form of closure

When Mr E. W. Lok dies, he does not want a funeral. The 59-year-old has end-stage lung cancer and only a few months to live, but his family does not know of his situation.

Mr Lok just wants to leave this world quietly because he has had enough of people being “kua suay” (Hokkien for “looking down” on him) .

However, he recently chose to do the “Last Interview” with social workers from charity Monfort Care recently.

It is part of a project in which terminally- ill clients give consent for the last few verbal exchanges between them and their social workers to be recorded and released online after they die.

“My social worker told me to leave no regrets, so perhaps, through the video, I can leave behind my life story to encourage the younger generation,” Mr Lok told The Straits Times in Mandarin.

The bachelor, who used to do odd jobs, has been struggling with low self-esteem and alcoholism for many years.

He felt there was nothing in his life to be proud of and turned to the bottle.

But his drinking problem ceased when he later started caring for his mother, who has schizophrenia and dementia.

Unfortunately, he had to give up his caregiving role this year when he found out he had cancer. Since then, he has started drinking again.

Said Ms Annie Lee, his social worker: “The Last Interview was more for him to review his life and for us to highlight his strengths so that he is able to get some form of closure.”

Getting ready for death

Stephen Says: https://www.youtube.com/ channel/UCCD0xdbDhi0nQ24QKy2G5bA

Good Death: http://www.gooddeath.org.sg

Life Asked Death: http://lifeaskeddeath.com

This article was first published on October 17, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.