Two Singapore companies are being probed by the authorities for allegedly scamming foreign workers out of thousands of dollars in payment for non-existent jobs overseas.

The police are investigating Global Catering and Management for allegedly cheating three Bangladeshis who paid the catering company about $5,000 for jobs in Canada.

They are also investigating Amacre Associates, an employment agency licensed by the Ministry of Manpower (MOM), for possible criminal offences related to offering non-existent jobs to foreign workers. The company has since changed its name to Amaicre in December last year.

The ministry is investigating Global for operating as an employment agency without a valid licence, and Amacre for possible breaches of its employment agency licence.

Both cases came to light after seven foreign workers made police reports. These workers had turned to Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (Home) for help last year.

“The cases involved low-wage migrant workers who were deceived about job opportunities overseas,” said Ms Tam Peck Hoon, who heads the team of volunteers that handled the complaints at Home, a group that helps migrant workers.

Both companies are not believed to be related but they follow a similar pattern of operation, she added.

They would hand out fliers at places where foreign workers gather, like Little India, promising jobs in Canada, Australia or New Zealand that pay more than $3,000 a month.

But the workers are required to pay more than $5,000 for visa applications, plane tickets and placement fees. The workers paid up, but the jobs did not materialise.

For example, in September last year, Amacre Associates allegedly gave three Bangladeshi workers employment contracts for housekeeping jobs purportedly offered by Buhler Industries, a company based in Winnipeg, Canada.

But when Home checked with the company directly, it replied that it had not offered the jobs. “This is a scam,” said a senior executive of the company in an e-mail to Home seen by The Sunday Times.

In all the cases, the agents who attended to the workers disappeared.

All the victims are work permit holders in Singapore. Most declined to be named because they did not want their bosses to know they were looking for jobs while they were still employed here.

A Sunday Times check found that both companies have either shut down or are operating from shell addresses that are similar to a numbered box in a post office.

Company records show that Global Catering and Management is owned by Mr Bharat Singh, an Indian national based in Britain, and Mr Ravichandran Krishnasamy, a Singaporean in his 40s. The company is registered to a shell address on the second storey of Textile Centre in Jalan Sultan.

Mr Ravichandran does not live at the address he gave to the Accounting and Corporate Regulatory Authority. When The Sunday Times visited the sixth-storey flat in Kitchener Road last week, an Indian woman said before closing the door: “He does not live here. He comes here once in a while to collect letters. He is my husband’s friend.”

Mr Ravichandran runs another company – Global Migration Administration – from another shell address on the 19th storey of Fortune Centre in Waterloo Street.

Amacre Associates, which is owned by Malaysian Kalai Chelvan and Filipino Venus Emperado Apas, moved out of its second-floor office in Lucky Plaza last year. The office is now occupied by a travel agency representing Philippine Airlines. “They left behind a photocopier that is spoilt,” said a staff member at the agency.

MOM’s website showed the agency brought 27 foreign workers into Singapore in the past one year and was slapped with six demerit points. According to the website, the company received the demerit points for misrepresenting MOM fees to work pass applicants.

Foreign worker advocacy groups say cases involving luring foreign workers with better-paying jobs overseas are common. Healthserve has handled about 20 cases in the last six months involving workers from China who paid between $500 and $1,000 each to two companies that promised them jobs in Australia.

None of the jobs materialised. Some of the workers have made reports with the police and MOM, said Healthserve case manager Jeffrey Chua. “All they are hoping for is to get back the money they paid,” he said.

‘Canadian dream’ turned nightmare

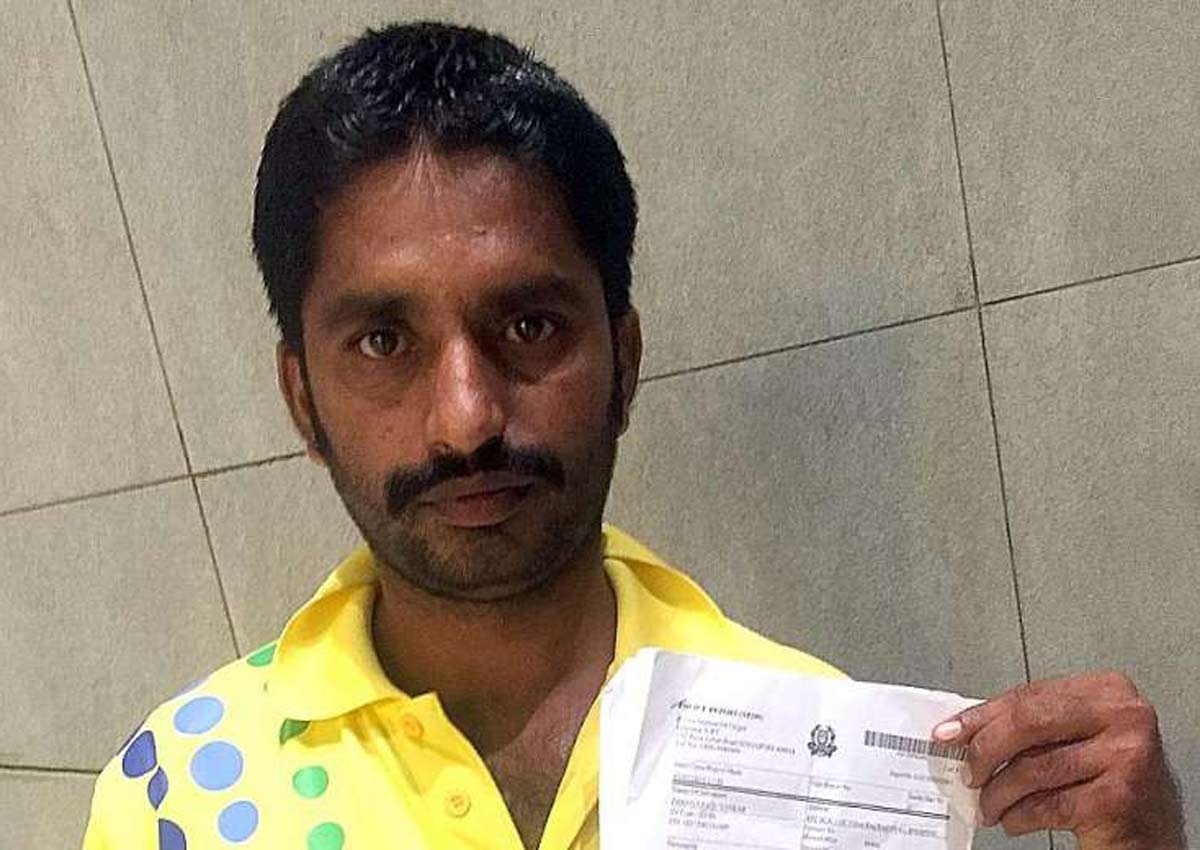

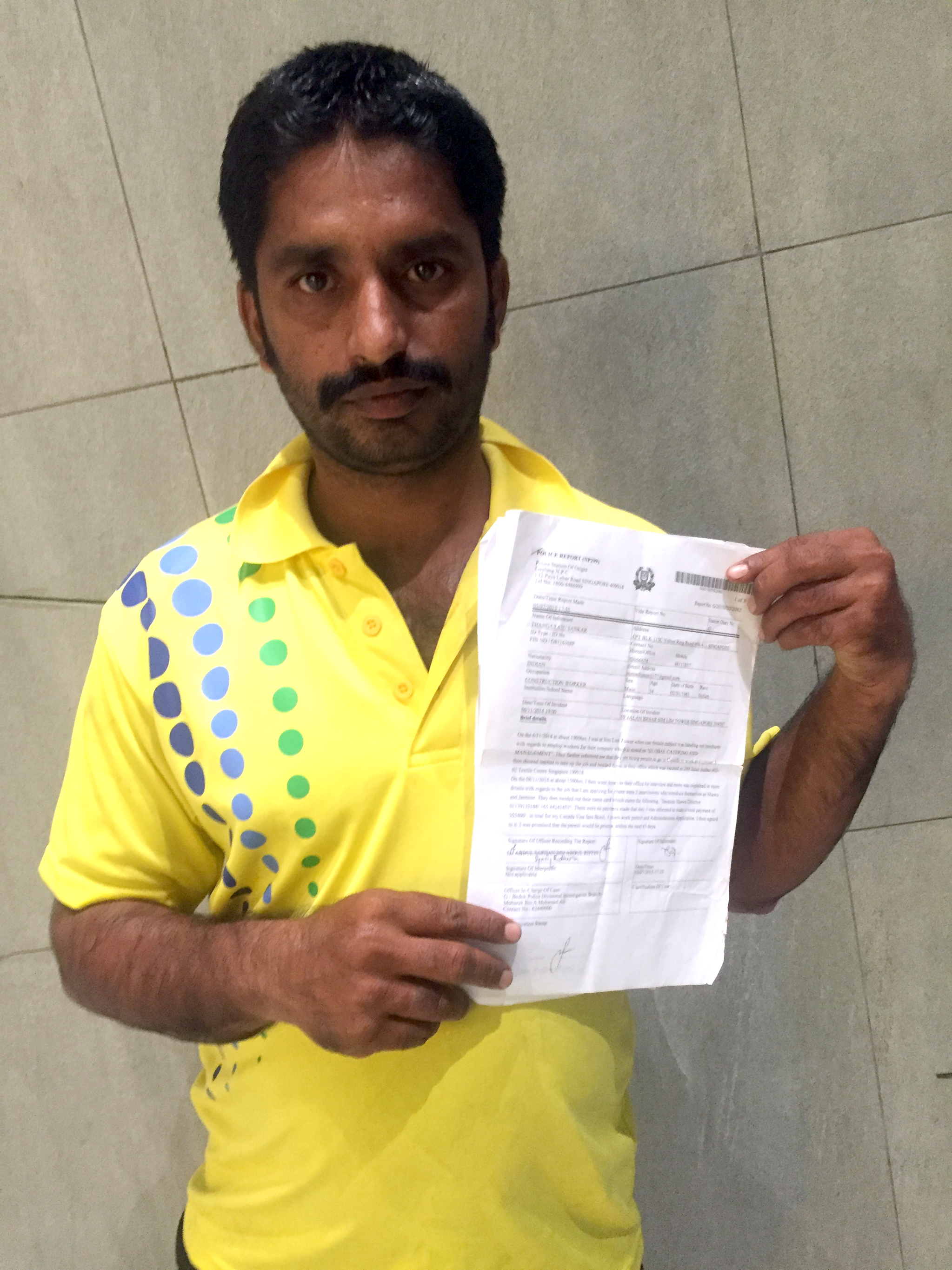

Grasscutter Thangarasu Sankar was looking to improve his family’s life when he decided to pay a company here $5,000 to help him get a job in Canada.

He was walking around Sim Lim Square with two friends in November two years ago when a woman approached him to ask if he was interested in working overseas.

She said she represented a catering firm looking for foreign workers, and that a job was guaranteed.

“I wanted to give my family a better life,” said Mr Thangarasu, 35, adding that his basic pay has been about $750 since he started working here in 2007. “She promised me that I would get at least C$2,500 ($2,635) every month and I can bring my family over.”

The woman told Mr Thangarasu and his friends to go to the office of Global Catering and Management in Jalan Sultan for an interview, which they did. Said Mr Thangarasu: “The company told us everything okay, guaranteed got job, but have to pay $5,000 to apply for three-year work permit. After working for two years, we can apply for Canadian citizenship and bring our family over.”

Mr Thangarasu was anxious to get the process started because he was planning to start a family. His daughter turned one last year.

Shawn, the firm’s employee who met them, also said they had to pay a deposit of $500. “I still have the receipt,” said Mr Thangarasu. But it is now a reminder of a tragedy that plunged his family deeper into debt. “The company said I cannot stay in Singapore when they applied for my visa, so I went home to India in December,” he said.

Back home, he took loans from the bank and his sisters to raise $4,500. He also sold his wife’s jewellery, and remitted the money to Global Catering and Management. “I received SMS from Shawn that my permit will be okay in 45 days and maybe the Canadian embassy will call me for interview,” he said. But the days came and went, without any word from either Shawn or the embassy.

Mr Thangarasu panicked. “I tried to SMS Shawn and call him, but he ignored me or sent me (vulgarities),” he said. He returned to Singapore last July, after paying an Indian agent $2,000 for a job here. He met Shawn in December, and the latter brought two men with him to the meeting at Woodlands Checkpoint.

“Shawn said he will cancel my work permit, and get gangsters to beat me up if I call him again. Now I’m scared, I think I will go back to India, be a farmer. But I owe so many people money,” said Mr Thangarasu.

Lured here by promise of jobs that do not exist

When construction worker Rasel J. M. dropped a drill on his leg and fell off a ladder in January, he was not taken to hospital. Instead, the Bangladeshi was told to stay in his hostel and take painkillers. Two days later, his employer confiscated his work permit and told him to go home.

It dawned on him that he could be working illegally as his permit stated he was working for his employer but in reality, he had been working for another company. “In that moment, I understood there was nothing I could do,” he told The Sunday Times through a translator. His father had sold his land to raise more than $9,000 to send him here to work. “I felt hopeless and afraid,” he said. “I had sacrificed so much.”

Mr Rasel, 32, is among a growing pool of foreign workers luredto Singapore by the promise of jobs which do not exist.

In the last five years, the Ministry of Manpower (MOM) has taken enforcement action against an average of 20 employers each year for such illegal importation of labour. It is currently investigating 23 employers for the offence.

Often, such employers would set up a shell company, in whose name they would apply online, with all the required papers, for foreign workers. But when they arrive, the workers are usually left on their own to find work or released to other companies who have reached their quota. Many are unaware they are breaking the law by working for an employer not stated on their permit.

In the latest case last month, company director Lim Kien Peng, 46, was jailed for two years and three months for bringing in 30 China nationals under MNF Investments and Holdings, a shell company he registered in 2008. Last July, MOM arrested 41 members of a syndicate that set up shell companies to bring in foreign workers for kickbacks. In 2014, it smashed three syndicates and arrested 19 people for setting up seven firms that brought in 500 workers for illegal employment.

Said an MOM spokesman: “We take a serious view of companies and individuals who commit such offences and will not hesitate to take strong action against them.”

Offenders could be jailed for six months or more and fined up to $6,000 for each illegal worker. If convicted of six or more charges, they are liable for caning.

Foreign worker advocacy groups say the problem has worsened. Operations manager Luke Tan of the Humanitarian Organisation for Migration Economics (Home) said: “Such cases are on the rise, compared to five years ago.” Home sees five to six cases every month.

Healthserve, a community clinic for foreign workers, dealt with 35 cases last year, and is now working on 10. Said its spokesman: “Most were caught with expired work permits which they say were cancelled without their knowledge.”

Mr Tan said the employers, after collecting recruitment fees, would terminate the work passes after a few months, freeing them to bring in new workers. Foreigners who work without valid passes face a fine of up to $20,000 or up to two years in jail or both, unless MOM determines they were victims.

Metalworker Yang Wei Xin, 44, from China paid an agent $14,500 to find him work here. He found his pass had been cancelled during a raid on his dormitory last August. He stayed on for eight months in Singapore to help with investigations, during which time he could not work. He returned home last week with a $9,000 debt and in despair: “How do good men make a living here?”

Boss demanded $14k, threatened to deport him

Frantic that his work permit had suddenly been cancelled five months after he arrived here, construction worker Gu Sheng Zhou called his employer repeatedly one day to demand why.

He got no answers. Instead, the 43-year-old’s employer picked him up in his car and dropped him off at a police station.

All had seemed rosy when Mr Gu first arrived from China in July 2014 for a job that promised up to $8 per hour. But when he arrived, his employer demanded $14,000 from him, threatening to deport him if he did not hand over the money.

He only worked for a total of 10 days at the company. The rest of the time, he was told to find his own work and lodging. The worst part, he said, was telling his family about his plight. “What would they think if I didn’t even give a reason for not sending money home?”

He has a wife and three children, who are still in school, back home.

After the police referred Mr Gu to the Manpower Ministry, he managed to find a job with another construction firm. But he still shudders when he thinks back on his last employer. “I don’t hate him. Hatred can’t resolve the problem, but I want him to return the money,” he said.

This article was first published on May 15, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.