His brush strokes have been compared to “works of experts 300 years ago” by respected critic and university lecturer Chen Chuanxi. His style of writing has been described as “uniquely powerful with the infusion of the expertise of eight ancient masters in calligraphy, including the sage of Chinese calligraphy, Wang Xizhi (303-361)” by national curator Yang Kairen.

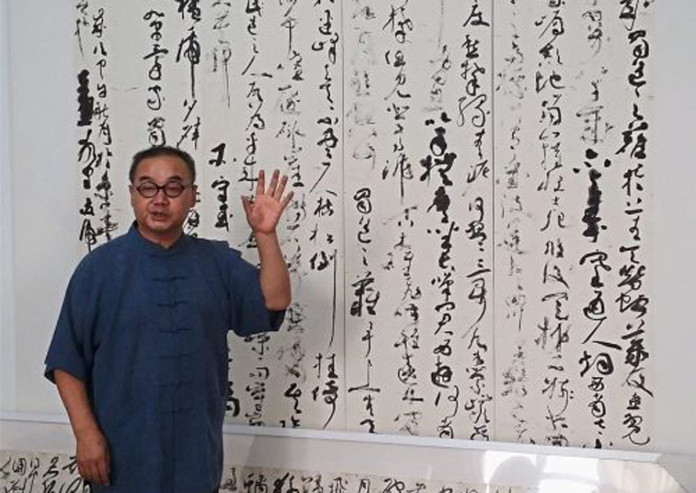

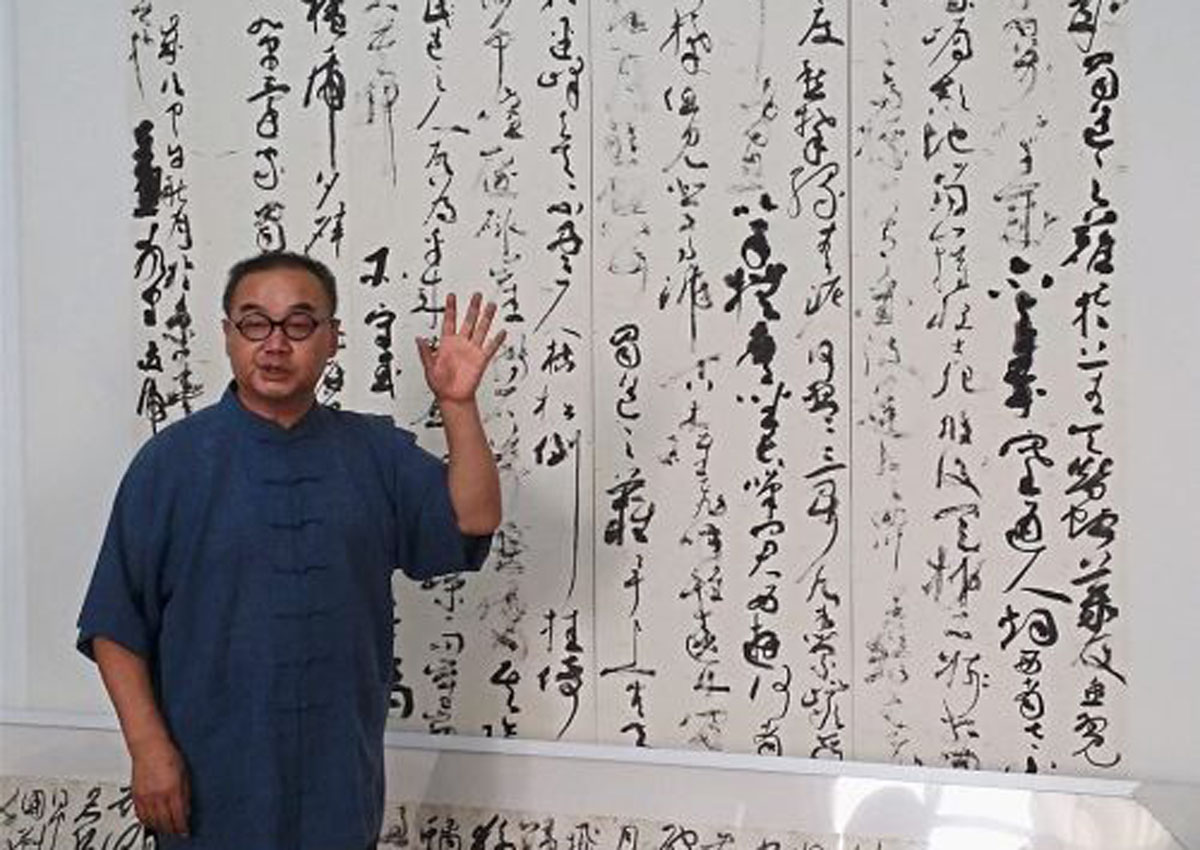

Meet 54-year-old Feng JunFu, one of China’s best known masters of grass writing or cursive calligraphy.

His brushmanship is backed by 40 years of study in Chinese civilisation.

Feng, a regular speaker on cursive calligraphy, now holds numerous influential positions – not only linked to calligraphy but also in politics.

He is a member of the Central Government Office Calligraphy Association Presidium, secretary-general of Aqsiq Calligraphy Association and leader of China GuoMen Calligraphy and Painting Institution.

He is also a member of the China Association for Promoting Democracy and the 12th Tianjin municipal committee of the Chinese People’s Political Consultative Conference (CPPCC).

But when met at his studio at Songzhuang Art Colony, a special arts and culture enclave about an hour’s drive from Beijing, Feng was a face of humbleness and warmth, with no airs about him.

Despite his achievements which have attracted praise from experts both locally and abroad, this Tianjin-based multi-award winner continues to push himself hard to produce passionate aesthetic works that have now become collector items.

“Everyday, I start writing calligraphy from 6.30am to 7.30am. After I finish my work at the office, I will do the same from 7.30pm to 11.30pm. This daily routine cannot be broken.

“When I go overseas, I will carry brushes, ink and paper with me. Calligraphy is a form of art that can only be perfected through non-stop practice and writing,” says Feng as he shows the hardened calluses on his fingers caused by the constant friction between the skin and brush pens.

Feng, who at 21 emerged the runner-up at China’s first national calligraphy competition in 1984, has mastered the difficult skill of controlling strength and finger pressure in writing caoshu, also known as cursive writing or grass writing – the toughest form of Chinese calligraphy.

In these scripts, individual characters flow in abbreviated form. At their most cursive, two or more Chinese characters may be linked together and the whole script can be written with a single flourish of the brush.

Feng is reputed for injecting life, action and emotion into his calligraphy. His famous copy of the poem River of Red is said to have imparted “a shockingly breathtaking, magnificent movement” and a sense of “storm raging in fury”.

His style of writing can be “bold and unrestrained like running horses and gushing water, and can be calm and slow like morning mist”, according to some comments on Feng’s works.

In recent years, Feng has gone on to broaden his skills in writing using bigger platforms – the floor, deserts and even on the banks of the Yellow River. His tools are no longer limited to brushes.

“In the Gobi Desert, I could pick up an empty bottle and write on a vast stretch of soil; in the open air, I could wield a bloom and write characters that came to mind,” Feng elaborates as he shows photographs that capture his flying strokes in open spaces.

But being an established calligrapher is not enough for Feng, who is also an active community leader and an emerging politician.

He wants to use his influence and standing to do some useful work for his fraternity.

Being a member of the Tianjin committee of the CPPCC, he and others have successfully persuaded the central government to include calligraphy in the school curriculum from primary school onwards. This ensures that budding calligraphers can earn a decent living.

“As a citizen, I must make some contributions to society. As a member of the CPPCC, I must forward people’s views to the government. Arts and culture can promote peace, harmony and social stability. Indirectly, this promotes political stability,” opines Feng.

Feng, who is often seen wearing a Tang suit, is also known for starting a movement to promote ink brush writing. He says: “I encourage anybody who uses chopsticks to eat to write calligraphy. These are key parts of Chinese civilisation.”

Indeed, he has in his studio calligraphy on his views on chopsticks and calligraphy.

As a person, Feng also believes in doing charity and social work.

Whenever there is a natural disaster, he will donate his works to raise funds for victims. His writing of the word “dragon” sold for 280,000 yuan (S$58,000) during a fundraiser for children who survived the May 2008 earthquake in Sichuan Province.

Feng also makes annual retreats to remote parts of China such as Xinjiang and Inner Mongolia to teach the non-Han children calligraphic writing.

“In my past trips, these children came dressed in their best and most colourful clothes to learn calligraphy as though they were going for a big festival. I was very touched by their enthusiasm to learn,” recalls Feng.

Outside China, Feng is a regular speaker on calligraphy, particularly in Korea, Japan and South-East Asia.

But he has a special bond with Malaysia. He has made more than 10 trips here for both official and personal reasons.

In 2005, he made his first trip to Malaysia when he was invited by the then Deputy Minister of Higher Education, Datuk Fu Ah Kiow, to hold a calligraphy exhibition and seminar in Kuala Lumpur in conjunction with the 30th anniversary celebration of Malaysia-China diplomatic relations.

Subsequently, Feng held seminars and exhibitions in Malaysia and Singapore on the invitation of other groups. More recently, his daughter enrolled in Kuala Lumpur’s Limkokwing University to pursue her masters degree.

“Malaysians strike me as people who love Chinese culture immensely. In 2009 during my seminar on calligraphy, the participants stayed up at night to learn. They even celebrated my birthday with me. That really moved me to tears,” says Feng.

He quips that he has since become a “cultural ambassador” for Malaysia as he has been encouraging his friends and relatives in China to visit “beautiful Malaysia” and send their children to study in Kuala Lumpur.

In a three hour-long interview, Feng talks to this writer about calligraphy and his ambition. Following are excerpts:

> I understand you majored in English in your tertiary education. Why didn’t you choose calligraphy?

People who are experts in calligraphy come from all kinds of backgrounds. For example, the sage of calligraphy Wang Xizhi was a general in the Jin Dynasty (265-420). He was a master of all forms of calligraphy, especially caoshu.

Chinese calligraphy is a key part of Chinese cultural and national heritage.

Coming from a traditional family and under the influence of my father (a carpenter), writing with an ink brush from young was mandatory. In addition, writing calligraphy can cultivate good character.

We normally choose beautiful poems or words of good tidings for calligraphy, as this spurs us to think positively and helps to mould us into good and happy persons.

While writing, you will have to concentrate and stay calm as you decide how much strength and pressure to exert while manoeuvring the strokes to coin the words. The ideal disposition takes years to attain. This is why there is a saying: “Calligraphy mirrors the author’s character.”

> Why did you choose to specialise in cursive writing?

I like caoshu because writing it is like a conducting a symphony orchestra.

In cursive writing, the brush strokes can be thin, thick or serious, but they can also be free from classical constraints. Although you have to follow the set rules, you can choose to exaggerate by elongating or broadening the strokes of the words. You can choose to control your strokes or let go … due to the numerous possibilities of bringing changes to writings, I see caoshu as reflecting changes in life.

> How do you rate your achievements in calligraphy?

It is not up to me to rate myself. You have seen the comments made about me by some leading curators and critics.

When can I hit the top? I don’t know. I am still learning from the ancient calligraphers. Learning is like climbing a mountain. At each level, you see a different type of scenery and enjoy a higher level of happiness due to your achievement.

> How do you rate calligraphy in Malaysia?

Chinese calligraphy cannot be divorced from the Chinese language and education.

Chinese education in Malaysia is relatively well-preserved. I understand that this is mainly due to the struggles of the late Chinese educationists like Lim Lian Yoke and Sim Mow Yu. Due to the high standard of Chinese education in Malaysia, its calligraphy has achieved the highest standard among South-East Asian nations.

I also notice that Chinese Malaysians care about promoting Chinese culture. During Chinese New Year, they organise calligraphy competitions. I really respect them for their contributions.

> Is there a market for calligraphy?

In China, there is certainly a bright future for calligraphers now that the government has included calligraphy in our school curriculum.

In international auctions, famous calligraphic works have fetched between 100.8 million yuan and 436.8 million yuan (RM62.7mil to RM271.7mil) per piece. The market for art and cultural works has boomed on the back of China’s economic prosperity.

But for me, a good artist who no longer has to worry about bread and butter issues should not be obsessed with producing works to meet the appetite and demands of the market. We should produce works that resonate with our inner calling, passion, thinking or character.

Hence for me, it does not matter how much my works fetch in the market. All I want now is to produce good calligraphic works.

Some Malaysians who have collected my works include former Cabinet minister Tan Sri Michael Chen, Tan Sri Yeoh Tiong Lay of YTL Goup and Datuk Fu Ah Kiow, chairman of Star Media Group.

> I read that you have been copying the Heart Sutra in your calligraphy. Are you a Buddhist?

Buddhism has become a part of the culture in China, along with Taoism and Confucius teachings. I am not a Buddhist, but I subscribe to its philosophies emphasising human kindness, forgiveness and inner calm.…

Though comprising only 260 characters, the Heart Sutra contains the core teachings of Buddhism.

I have copied the Heart Sutra 10,000 times. I feel a sense of calm and tranquillity every time I write it.

I plan to invite 100 Buddhist monks to ink their signatures on 100 of my calligraphic works on Heart Sutra. At the moment, I have completed about 70 pieces.

> What is your ultimate ambition? To be an influential politician?

Study well, make progress everyday. This means I will continue to learn from the ancient esteemed calligraphers so that I can achieve progress everyday. I have no high ambition in politics, but I believe my talent in calligraphy will help me achieve more in this field.