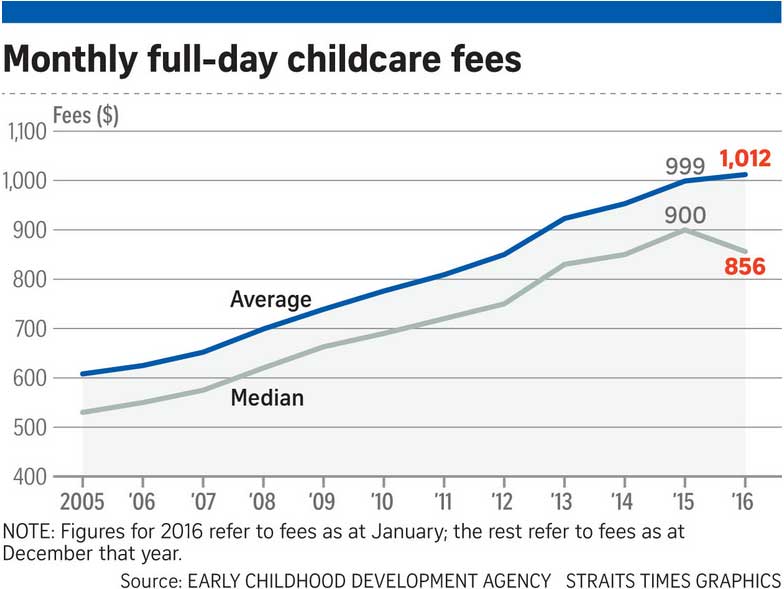

It has been getting more expensive to raise children here, but there is a bright spot for some parents.

The median monthly fee for full-day childcare fell from $900 last December to $856 in January – the first drop in at least a decade.

But the average fee also rose by $13 from $999 to $1,012 over the same period. Experts say it is not clear if the drop in median fees would moderate fee increases across the childcare sector, which faces rising manpower costs amid a shortage of teachers.

The median fee separates the cheaper half of the 1,200-plus centres from the rest. The average fee is higher as the high fees charged by some centres – which can be over $2,000 – skew the data.

The Early Childhood Development Agency (ECDA), which oversees the childcare sector here, released the data to The Straits Times last week.

The drop in median fees comes after 169 centres run by 23 operators made a one-off fee reduction in January, as required under the new partner operator (POP) scheme.

This supports small and mid- sized operators, and complements the anchor operator (AOP) scheme, which is for larger operators that offer at least 1,000 places.

Both types of operators get government grants, but have to cap fees – at $720 a month for full-day childcare at AOP centres, and $800 for similar programmes at POP centres.

Lower fees do not mean lower quality. An ECDA spokesman said operators under the schemes have to meet quality criteria.

At Bright Juniors, a brand under G8 Education Singapore, five of its seven centres are under the POP scheme. Besides sending staff for training, it has nominated teachers for ECDA’s Professional Development Programme, which lets pre- school staff spend 180 hours over three years on courses and projects that prepare them for more responsibilities at work.

Ms Jane Choy, general manager (business operations) of G8 Education Singapore, told The Straits Times: “We believe in fostering talent through professional development, training and support.”

As of last October, AOP and POP centres made up about 40 per cent of the market, and this is expected to increase to half by 2020.

Operators which are not on either scheme said they are mindful of price competition and how fee increases affect parents, but said their priorities are in maintaining quality, which makes it difficult to avoid raising fees.

Ms June Rusdon, chief executive of Busy Bees, which runs more than 50 centres, said: “Operators that are not on either scheme… cannot compete as effectively on quality as they would have been able to in a free market.

I am hopeful that tactics to attract or retain customers would still be in spurring quality improvements, not rampant cost cutting.”

Dr T. Chandroo, chairman of Modern Montessori International, which runs 30 centres here, said it is inevitable that hiring qualified staff and high-quality programmes lead to fee increases.

Dr Chandroo, who is also chairman of the Association of Early Childhood and Training Services, which has 18 childcare operators running about 700 centres, added: “Any fee increase is not just about making more money.

“It is a matter of sustainability to continue the business.”

Parents said it was not just about costs – they also cared about quality of the childcare services.

Tuition agency owner Kelly Goh, 32, who has a three-year-old son in a childcare centre that is not under any of the schemes, pays more than $900 in childcare fees per month.

She said: “I have seen other centres which charge lower fees and they just meet the minimum standards required, but the teachers have attitude problems… I would rather pay a bit more for better quality.”

This article was first published on March 21, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.