SINGAPORE: The Monetary Authority of Singapore (MAS) said on Monday (Sep 21) it is “closely studying” media reports mentioning Singapore banks in potentially suspicious transactions that were flagged to authorities in the United States.

In response to CNA’s queries, it added that it will take “appropriate action” based on the outcome of its review.

Over the weekend, media reports, citing leaked secret documents that were confidential reports made to the US government, said global banks have facilitated more than US$2 trillion (S$2.72 trillion) in “suspicious” transactions filed with the US authorities over nearly two decades.

READ: FinCEN documents reportedly show banks moved illicit funds

The three local banks – DBS, OCBC and UOB – were named in a sample of transactions extracted from the documents, dubbed the “FinCEN Files”.

The MAS said it is aware that Singapore banks were mentioned in these media reports.

“Although suspicious transaction reports in and of themselves do not imply that the transactions are illicit, MAS takes such reports very seriously,” wrote the spokesperson in an emailed reply.

“MAS is closely studying the information in these media reports, and will take appropriate action based on the outcome of our review. Singapore’s regulatory framework to combat money laundering meets international standards set by the Financial Action Task Force,” it added.

WHAT ARE THE FINCEN FILES

The media reports which emerged over the weekend were partly based on leaked documents called suspicious activity reports (SARs) that banks and other financial institutions filed in the United States with the US Department of Treasury’s Financial Crimes Enforcement Network (FinCEN).

Financial firms in the US are required to file such reports to the US authorities when they detect activities that may be suspicious, such as money laundering or fraud, although they may not necessarily be proof of wrongdoing or crime.

BuzzFeed News obtained more than 2,100 of these SARs and shared them with the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists (ICIJ). The ICIJ then gathered a team of more than 400 journalists from 110 news organisations in 88 countries to investigate the documents.

The ICIJ report, which followed a 16-month-long investigation, said the SARs contained information showing more than US$2 trillion worth of suspicious transactions between 1999 and 2017.

Germany’s largest lender, Deutsche Bank, reportedly facilitated more than half of these transactions flagged to the US authorities. Other global banks that appeared most often in the files included Bank of New York Mellon, Standard Chartered, JPMorgan and HSBC, according to the report.

The ICIJ also noted that while SARs reflect the concerns of watchdogs within banks, they are “not necessarily evidence of criminal conduct or other wrongdoing”.

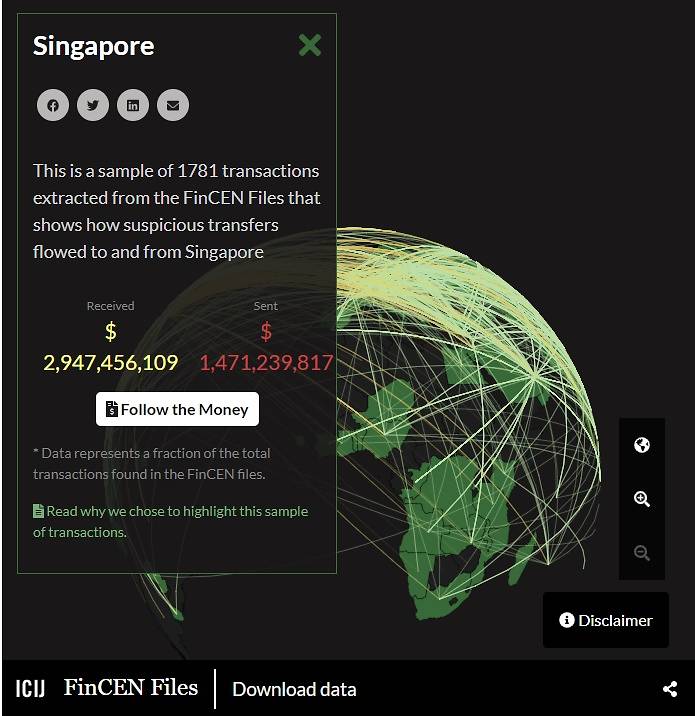

A map published on the website of the ICIJ sought to depict movements of “a fraction” of the transactions found in the “FinCEN Files”.

“The map only displays cases where sufficient details about both the originator and beneficiary banks were available, and is designed to illustrate how potentially dirty money flows from country to country around the world, via US-based banks,” said the ICIJ, noting that the map illustrates 18,153 transactions worth over US$35 billion that were flagged as “suspicious” between 2000 and 2017.

TRANSACTIONS THROUGH SINGAPORE

A total of 1,781 transactions flowed through Singapore, with nearly US$3 billion entering the country and about US$1.5 billion flowing out, according to the map by ICIJ.

A screenshot of the transaction map from the website of the International Consortium of Investigative Journalists.

DBS and UOB each accounted for more than 500 of these “potentially suspicious” transactions, while OCBC had 62 transactions that took place between 2000 and 2017.

All three banks were listed multiple times in the ICIJ map. In one such entry, US$596.8 million was said to have been sent from DBS, with US$228.3 million moving into the bank over 461 transactions.

The ICIJ map also contained examples of how transactions flowed between Singapore, the US and 46 other countries, though it did not state the reasons why they were potentially suspicious.

For instance on Feb 5, 2014, around US$40 million was moved from Swiss bank BSI to DBS in a single transaction.

Slightly more than US$20 million was moved from OCBC Wing Hang Bank Limited – OCBC’s subsidiary in Hong Kong – to DBS via two transactions from Nov 22 to Dec 22 in 2016.

In another example, 29 transactions totalling US$24.4 million were made from Russia’s Specsetstroybank to UOB from Jul 10 to Aug 19, 2013.

Other foreign banks with offices in Singapore that were named included CIMB and Deutsche Bank.

For instance, in 294 suspicious transactions between 2000 and 2017, US$250.4 million was sent from CIMB, with US$34.3 million moving in the other direction.

LOCAL BANKS SAY

When contacted, a DBS spokesman said the bank has “zero tolerance for bad actors abusing the financial system” and that it stands united with the financial industry in collaborating with authorities to seize funds and disrupt criminal networks.

“We note that outside of sanctions on names or specific account freezes, it is generally very difficult to delay or intercept money in transit given the impact on legitimate business, so the normal process – which happens behind the scenes – involves subsequent investigations to establish suspicion, based on which the necessary action is taken,” the spokesman added.

OCBC said it has a “comprehensive and robust” anti-money laundering and terrorist financing framework (AML/CFT) across the group, which comprises methodologies and programmes that are “in full compliance” with local regulations and incorporates international best practices.

“We recognise that money laundering is an area of growing concern and we have, and will, continue to invest substantially in technology to develop data analytics capabilities to enhance and optimise our competencies in early identification of money laundering,” said OCBC’s head of group AML/CFT Fairlen Ooi.

This includes the use of artificial intelligence and machine learning to detect suspicious transactional activities, as well as the formation of specialist teams that include data scientists and IT engineers, said Ms Ooi.

Similarly, UOB said it has in place “robust prevention, detection and enforcement measures” when it comes to fighting money laundering.

This includes risk assessment, customer and counter party due diligence, transactions monitoring as well as investigating and reporting potential suspicious activities to the relevant regulatory bodies, said its head of group compliance Victor Ngo.

“We continue to enhance our anti-money laundering capabilities through the use of technologies including artificial intelligence and machine learning,” he added.

SARs are equivalent to a suspicious transaction report (STR) in Singapore,which is filed by banks with the Commercial Affairs Department (CAD).

An STR contains financial information and is filed when there is reason to believe the funds involved are related to crimes like money laundering or terrorism financing.

The CAD’s Suspicious Transaction Reporting Office received 32,660 of such reports in 2018, down from 35,471 in 2017, according to the CAD’s latest annual report released in September last year.

Banks filed the bulk of STRs in 2018, with 16,314 reports made.