In the long and remarkable career of S R Nathan, the Laju hijack of 1974 had all the ingredients of a thriller movie, with the future president of Singapore playing a starring role.

The young today may find it hard to reconcile the jocular grandfather figure with the steely hero of Singapore’s hostage drama.

When he boarded the Japan Airlines plane at Paya Lebar Airport with Singapore government officials and commandos to guarantee the safe passage of four terrorists bound for Kuwait, Singapore and his family did not know if he and his team would make it home alive.

The drama was played out at a time when there was no Twitter, no Facebook and no live blog to give a blow-by-blow account of what happened.

What the Singaporean team had was guts and gumption.

Mr Saraj Din, 71, a former officer in the Internal Security Department (ISD), who was on the Feb 8 flight, said of Mr Nathan: “He managed to save all our lives when we were all very uncertain of the outcome.”

The drama had started on Jan 31, when four terrorists equipped with sub-machine guns and explosives landed on Pulau Bukom.

Their plan was to blow up the Shell oil refinery on the island to disrupt the oil supply from Singapore to South Vietnam to show their support for communist North Vietnam during the Vietnam War.

Two were Arabs from the Popular Front for the Liberation of Palestine and two were Japanese nationals from the communist militant group Japanese Red Army. The two groups believed in changing the world through revolution, and trained together in guerilla warfare in the Middle East.

On Bukom, they planted explosives at three oil tanks but the blasts caused little damage, and the rest of the explosives failed to go off.

Chased by the police, the terrorists hijacked a ferry at Bukom jetty called Laju, or “fast” in Malay – and held five crew members hostage.

After six days of protracted negotiations, the bombers agreed to release the hostages in exchange for safe passage out of Singapore.

Their destination: an Arab country. But no one would take in the terrorists until another group of terrorists stormed the Japanese Embassy in Kuwait, taking hostages and demanding that the Japanese government send a plane to Singapore to take the Laju terrorists to Kuwait.

On Feb 7, the bombers were taken to Paya Lebar Airport, where they surrendered their weapons and released the remaining three hostages. Two hostages had escaped earlier.

The terrorists were to board a special flight to Kuwait on a plane loaned from Japan. But they had one condition: They demanded a group of guarantors to accompany them on the flight.

Then Deputy Prime Minister and Defence Minister Goh Keng Swee needed a man who would not buckle under pressure to lead the dangerous mission.

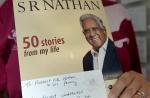

He turned to Mr Nathan, then 49, and the director of Singapore’s external intelligence agency, the Security and Intelligence Division (SID) in the Ministry of Defence.

Mr Nathan had been involved in the negotiations with the hijackers from the start.

The other 12 members of the team were drawn from government units handling the crisis: the ISD, police, Singapore Armed Forces commandos, and translators: Mr S. Rajagopal, Mr Saraj Din, Mr Tee Tua Ba, Mr Yoong Siew Wah, Mr Seah Wai Toh, Mr Andrew Tan, Mr Tan Kim Peng, Mr Gwee Peng Hong, Mr Teo Ah Bah, Mr Tan Lye Kwee, Haji Abu Bakar and Haji Rahman.

If Mr Nathan was afraid, he did not show it.

In separate interviews with The Straits Times and The New Paper decades after the incident, he recounted how he broke the news of the mission to his wife Urmila. Their children were then 15 and 11.

“I just looked at her and told her, ‘I’m going’,” Mr Nathan said.

“I knew it’d be very emotional for her and for my children… I had to display some confidence.”

When he left for the airport, he avoided looking at any of his family members in the eye.

In an interview with The Straits Times, former ISD officer Rajagopal, 76, recalled then Minister for Home Affairs Chua Sian Chin telling the group at the airport on Feb 8: “Thanks for your service. If anything happens, we will take care of your family.”

During the 13-hour flight, the thoughts swirling in Mr Nathan’s head veered from the personal – Would he see his wife and children again? – to the practical – Would the plane be allowed to land in Kuwait or would they be forced to refuel and sent off elsewhere?

Would the hijackers refuse to let the Singaporeans go and use them as bargaining chips? Everything was up in the air. But Mr Nathan steadied himself with these words: “Have faith and do your duty.”

Demonstrating the diplomatic skills that he showed in the foreign service, he chatted with the terrorists and tried to win their trust.

Mr Tee, who was then 31 years old and the officer-in-charge of the Marine Police, recalled: “In the plane, Mr Nathan asked me to engage them, talk to them, and as I was talking to them he would join in.”

Mr Tee, 74, later became Commissioner of Police.

“Mr Nathan was quite relaxed, because by that time the terrorists had surrendered their guns. He cracked some jokes, tried to break the ice.”

Mr Nathan’s goal was to establish rapport with the terrorists, in case negotiations soured and endangered the lives of the Singaporeans on board the plane.

When they landed in Kuwait before sunrise, they were greeted by a wall of tanks, armoured vehicles and soldiers.

It “looked like the middle of a war zone”, Mr Nathan wrote in his 2011 memoirs, An Unexpected Journey: Path To The Presidency.

It became clear that getting the Singapore team off the plane was not one of the Kuwaitis’ priorities. It seemed likely that the group of terrorists in the country would be bundled onto the plane and flown to a new destination with the Singaporeans on board.

But Mr Nathan had a plan, said Mr Tee. He told the air traffic controllers he had an important message from Singapore’s Prime Minister and needed to speak to “somebody high up”.

Tense hours passed. The group could not do anything but wait on the tarmac.

“For four to five hours, we were eating instant noodles in the plane and just waiting, so you can imagine our frame of mind,” Mr Tee recalled.

Then a fleet of cars approached with lights flashing and sirens blaring. One of the cars, a Cadillac, carried the Kuwaiti Defence Minister, who had finally arrived to negotiate.

Mr Nathan pressed Singapore’s position, which was that the team had done their part in bringing the hijackers to Kuwait. Subsequent negotiations were between the Kuwaiti and Japanese governments, and the Singaporeans should be allowed to return home. He stressed that the Singapore team was on Kuwait soil and thus came under the protection of the Kuwaiti government.

The Kuwaiti Defence Minister rebuffed him several times and told him to shut up.

At one point, he threatened to arrest Mr Nathan.

“Mr Nathan was very calm but very determined… It was not an easy situation to handle, how much can you push the line?” said Mr Tee.

The hours ticked by. Mr Nathan left the plane several times to negotiate with the Kuwaitis and the Japanese ambassador.

The breakthrough came with the arrival of Kuwait’s Foreign Minister. After more talking, he finally told Mr Nathan: “All of you get down and get lost.”

The Singapore delegation did as they were told.

The Kuwaiti Foreign Minister told Mr Nathan that the Singaporeans should make themselves scarce until their flight home was due, in case the hijackers demanded they be put back on the plane if negotiations with the Kuwaitis did not go well.

So the team did what Singaporeans do best – they went shopping. Mr Nathan gave each member of the team US$100 and they disappeared into a bazaar.

They met later that day to catch a Kuwaiti Airlines flight to Bahrain. From there, they boarded a Singapore Airlines flight home. They arrived in Singapore around sunset on Feb 9.

Mr Rajagopal described how Mr Nathan rose to the occasion: “He was a good negotiator, a brave man in a foreign country. He took care of us, comforted us, and gave us direction.”

But the man of the hour did not make a big deal of the fraught situation. He told The New Paper: “It was a job I did. It was an episode we all wanted to forget.”

A month before Mr Nathan stepped down as president in 2011, he invited the group involved in the Laju incident to tea at the Istana.

Mr Saraj said they talked about Singapore’s tense formative years: battling the communists, racial unrest and other security problems.

“Young people these days see Mr Nathan as a father figure, but they don’t know him in his younger days. The situation in Singapore then was entirely different.”

It was a time for a generation of “pragmatic leaders” like Mr Nathan, who could handle these situations, said Mr Saraj.

“With the passing of Mr Nathan and Mr Lee Kuan Yew, that generation of leaders is largely gone.”

This article was first published on Aug 26, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.