SINGAPORE: Reversing into a gravel-laden road, the first glimpse of Mr Makoto Koike’s cucumber farm came into view. It was a sight for sore eyes, having travelled more than three hours from Tokyo to reach the sleepy town of Shirasuka in the Shizuoka Prefecture.

As greenhouse farms go, it looked pretty unremarkable, with transparent tarpaulin covering the 38-year-old farmer’s prized produce – the Japanese cucumber.

But behind the scenes, strange things were happening. The visionary farmer is using technology to help transform the way a decades-old family business operates.

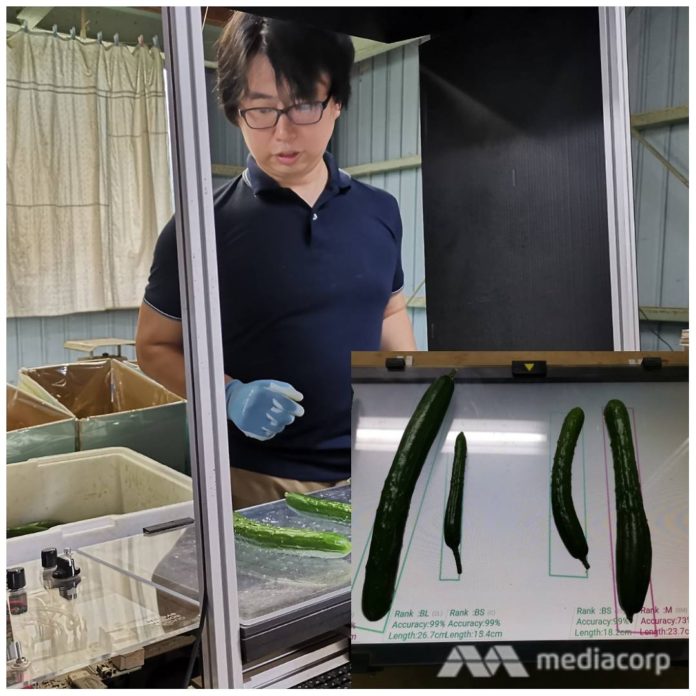

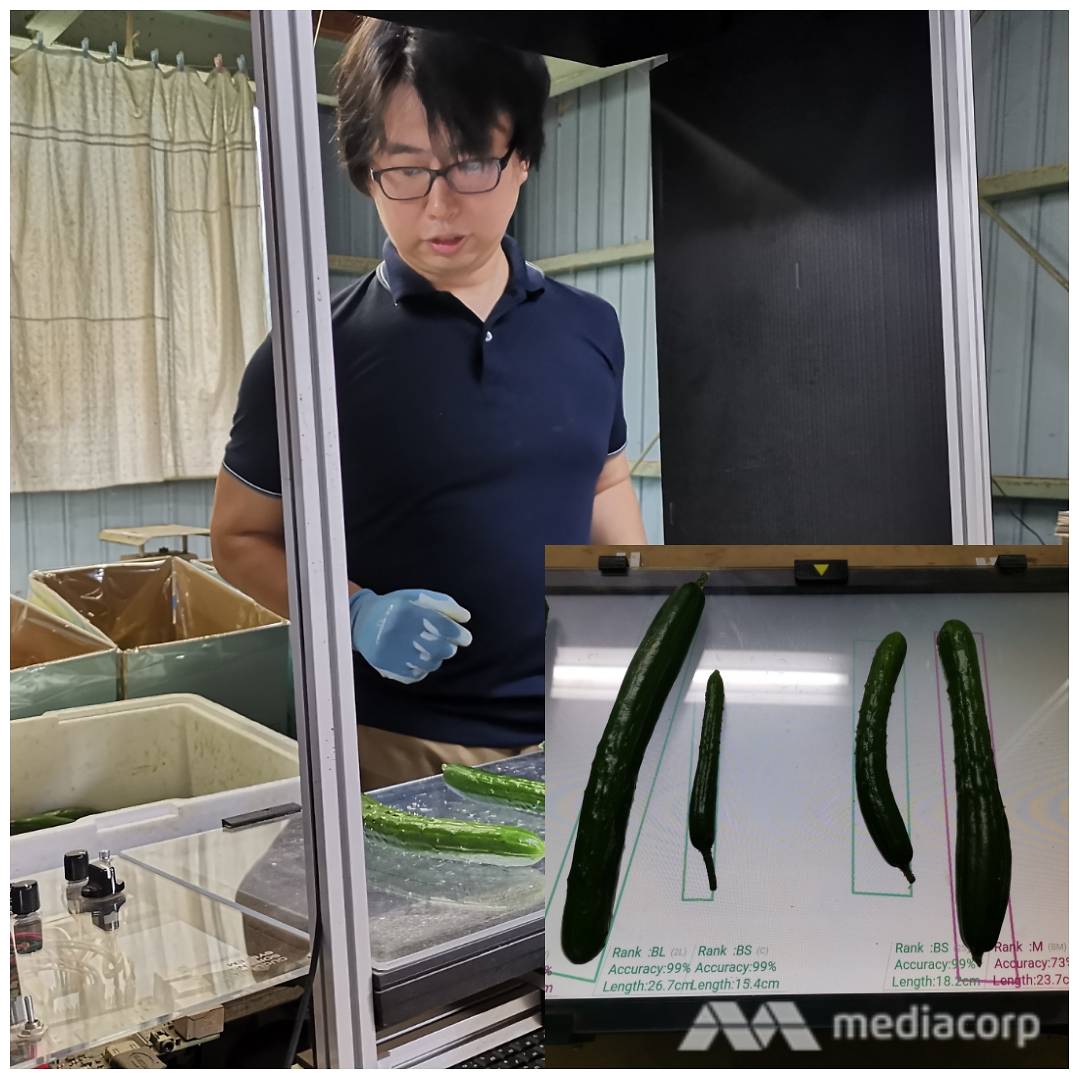

Every day at around this time of year, the farm produces about 100kg – or about 1,200 cucumbers – and this could go up to 500kg during the peak harvesting season. These then have to be sorted according to nine different quality grades depending on the cucumber’s attributes like size, shape, consistency and colour, Mr Makoto explained when CNA visited the farm last month as part of a Google-organised media trip.

A discoloured or out-of-shape cucumber is deemed inferior to one that is consistently straight and dark green all the way through.

This sorting process is crucial to the family’s business given that premium-quality Japanese cucumbers are highly sought after, particularly by sushi establishments around the country. During the winter peak season, 5kg of these cucumbers can go for anything between 1,000 yen (S$12.54) and 2,000 yen (S$25.10), he said, adding that its value drops to about 800 yen (S$10) for the same amount during the off-peak summer season.

Yet the bulk of the sorting process has been carried out by his 64-year-old mother Masako, who needs about 2-3 hours to sort about 50kg of cucumbers at any sitting, Mr Makoto pointed out. During the peak season, he said she could spend eight hours straight just identifying the different grades of cucumbers and throwing them into the various boxes in the family’s musky, cluttered shed.

To alleviate her workload, he turned to artificial intelligence (AI) for help. In 2016, the former auto industry engineer leaned on his programming language skills and picked up AI – specifically Google’s open source machine learning tool TensorFlow – to figure out how to automate the very tedious and manual process of sorting the cucumbers.

The first iteration of his AI-enabled cucumber sorting machine achieved an accuracy rate of 60 per cent when benchmarked against his mother’s judgement, he said.

The second was even more accurate – at 80 per cent – but he said it required too many cameras (three) and the process involved putting each cucumber in a container for detection before the vegetable is dropped on a conveyor belt and packed off in boxes of different grades.

His latest generation contraption can sort up to 10 cucumbers at a go using just one camera, but this meant accuracy suffered – it is now at 70 per cent, the second-generation farmer shared even as he continues to fine-tune the home-brewed mechanism that cost about US$200 to put together.

So why is he investing so much time and effort developing this sorting equipment?

“We needed some consistency. Previously, my mother was the only one doing (the sorting) … but now anyone can help out,” Mr Makoto explained.

“My mum is not very interested in this (AI), but she was impressed by its accuracy,” he added with a laugh.

As a result, the farm’s yield has improved by 140 per cent. The extra time saved from sorting is used on other aspects of farming like researching how other data like temperature and watering of the crop could be automated, Mr Makoto said.

Mr Makoto Koike showcasing the third generation of his homebrewed cucumber sorting machine, which he says has an accuracy of 70 per cent.

PESKY PEST PROBLEMS

Mr Makoto’s cucumber-sorting machine is but one of many AI-driven projects sprouting up to solve some of the world’s agricultural problems.

Over in India, the battle lines have been drawn against the pink bollworm, whose innocent-looking larvae can wreak havoc on the country’s cotton fields on a scale which belies its miniscule size.

The Wadhwani AI institute, set up by brothers Romesh and Sunil Wadhwani last year, identified cotton farming as a problem area it wants to solve. Vice president for Products and Programs Raghu Dharmaraju explained why, citing the example of 2013 when about 50 per cent of the country’s crop was lost due to an infestation of pink bollworm despite the fact that 55 per cent of all pesticides used in India are by cotton farmers.

The pink bollworm is a highly invasive insect whose larvae damages the cotton fibres and reduces its yield and quality, according to the US Department of Agriculture’s website.

Yet, many of the farmers in the field who are leading the battle against the pesky bollworm are fighting with one hand tied behind their back – they simply don’t have access to enough information to destroy the larvae. They are reliant on field staff deployed by a centralised agriculture agency, but they are themselves over-worked and under-resourced, Mr Raghu said.

A field worker inspecting the pest trap on one of the cotton farms in India. (Image: Wadhwani AI’s website)

Each field staff would have a smartphone and have to visit every farm under his or her care to check on pest traps. They then have to manually count the pests and submit the findings, after which an expert assigned to them will provide advice on the next steps to take, Mr Raghu explained during an interview.

To address the manual process and field workers’ inability to recognise all types of pests, the Wadhwani AI institute is working on a machine learning tool that can recognise three of six most common pests that afflict cotton crops – pink bollworm, American bollworm and jassids, Mr Raghu said.

With this AI model integrated to the app the field staff are already using, they can send the relevant information back in a more timely and efficient manner, he said.

“(This means) the identification (of pests) can be more accurate and the counts are more accurate,” he said.

And every second counts in the fight against these invasive pests, given that the bollworm eggs hatch in three to seven days.

“You want to catch it as soon as possible, right? We want to know immediately.”

The data would also better guide the farmers’ pesticide use so they don’t err on the side of caution and over-spray.. “Too much pesticides spoils soil,” said the vice president.

Mr Raghu said his team recently scaled the model down to a size that can be downloaded to most phones, thus allowing for offline use. It is preparing to equip about 50 to 100 field staff, also known as extension workers, with the AI tool for the coming crop season, he added.

AI, MISUNDERSTOOD?

While AI can offer solutions to many of today’s problems, one fear may be holding up its more widespread use: That robots and technology are stealing people’s jobs and cannot be trusted. Frequent news headlines playing up the possibility of humans losing jobs to automatons add to such concerns.

READ: A world ruled by robots? This artificial intelligence expert paints a different reality

Experts advocating the benefits of the technology say it is important for people to understand more about it and how it’s being used, instead of succumbing to commonly held misconceptions.

AI expert Luis Gonzalez acknowledges that while worries about a dystopian future dominated by rogue robots may be unjustified, for some people these concerns are very real. To break down such perceptions, the Elements AI managing director for Asia Pacific suggests thinking of AI as like teaching a kid how to boil an egg.

“Machine learning would be you taking the seven-year-old along and then showing them how you would cook an egg,” he said. “With the machine learning model, that seven-year-old will be able to learn from how you do it and repeat that same learning. But it requires that you show how you cook the egg.”

The other method is to use a neural network, widely known as deep learning, to achieve the same outcome, Mr Gonzalez said. This method has been used since 2012 and shot into prominence with AlphaGo, the programme developed by Google’s DeepMind unit that defeated top Go player Lee Se-dol, back in 2016.

Returning to the egg cooking example, he said: “The latest iteration of artificial intelligence is you not showing the seven-year-old how to cook an egg. We’re just giving them the function, saying: ‘Cook an egg.’ And then the seven-year-old goes and looks at videos of people cooking eggs, gets data about what eggs need to be cooked, what utensils there are and then comes up with its own procedure.

“Why is deep learning powerful? When you have enough computing power and data, that seven-year-old is going to outperform you in cooking that egg. It’s going to cook a much better egg, it’s going to do it faster and it can cook a thousand within five minutes. No human alone can do (this).”

He also pointed out when AI should be tapped on ahead of humans: Any decision that requires two seconds or less.

“Those decisions, at some point, whether it’s how you cook or how your appliances purchase your food or which train you take and which taxi you flag down – these should not be done by humans anymore. Because the machines can a much better job at making those decisions,” Mr Gonzalez said.

He cited the mundane task of getting groceries as an example.

If you have just S$50 a month for groceries, and want to stretch that amount as far as possible, you can simply tell your refrigerator to solve this problem. You can then get your groceries from whichever source, but always within your budget, he explained.

(Illustration: Kenneth Choy)

WHEN AI BECOMES A BAD MYSTERY

Like with any other technology, AI is considered neither good or bad until someone actually makes use of it.

Take one’s personal health data, for instance.

If the machine is just fed a stream of data that includes your health condition, lifestyle and diet to analyse, it would be able to recommend the amount and type of exercise to do to ease that hip pain or the type of food to take to reduce one’s acid reflux, Mr Gonzalez elaborated.

The danger is when consumers – the ones who provide their personal data – don’t know how companies are developing these algorithms and coming up with the suggestions, and if profits was the primary consideration.

“Imagine I’m in a world where data of my daily morning routine gives me a sense of what I should eat that day or how I should exercise,” Mr Gonzalez said.

“My biggest fear is that because Big Pharma sponsors that platform and the recommendation, there will be a prioritisation for me to be sick of a particular illness so as to maximise (the pharma company’s) drug sales and profits … in spite of my own health.”

He cautioned: “This is where ethics and explainability really matter a lot.”

READ: AI in 2019 – Here’s what tech giants are betting big on

The AI expert is not alone in his concerns. AI ethics and explainability are top of the agenda for many industry groups and regulators around the world given its vulnerability to support unscrupulous business practices like those mentioned earlier and authoritarian governments.

For example, the European Commission (EC) said this April that companies working with AI need to install accountability mechanisms to prevent it from being misused under new ethical guidelines. AI projects should be transparent, have human oversight, have secure and reliable algorithms and be subject to privacy and data protection rules, it said.

“The ethical dimension of AI is not a luxury feature or an add-in. It is only with trust that our society can fully benefit from technologies,” said the EC’s digital chief Andrus Ansip.

Singapore, too, is keeping a close eye on this matter.

Minister for Communications and Information S Iswaran introduced its Model Artificial Intelligence Governance Framework at this year’s World Economic Forum. The guide will help provide a compass for companies developing AI solutions ethically, as it recommends making these transparent, explainable and fair to consumers.

AI’s ethical considerations could perhaps take a reference point from another technology CRISPR that, when used wrongly, has wide-ranging ramifications.

Last November, a Chinese scientist He Jiankui revealed that he used the CRISPR gene-editing technology to alter the embryonic genes of twin girls to protect them from being infected with HIV, the virus that causes AIDS. The revelation created an uproar within the research community, prompting more than 100 scientists to denounce the deed as “crazy” a day after he had posted the news on YouTube.

Critics said the twins could now face increased risks from other viruses and, down the line, potentially pass on harmful side effects to their offspring.

Investigations have since been carried out against He, and also prompted Chinese president Xi Jinping to call for new regulations on gene editing at the start of this year.

IMMENSE POTENTIAL FOR GOOD

It is clear the ethical considerations and rules governing the development and use of artificial intelligence should not be neglected. Equally, there is a need to give space to innovative, well-meaning entities the space to play in this space and come up with new solutions to age-old problems.

Take climate change and, specifically, global warming. Most people know that this phenomenon is taking place and changing how the Earth is functioning. One of the main reasons for this is the increasing lack of green cover caused in part by deforestation.

This is where a San Francisco-based non-government organisation (NGO) hopes to play its part in combating illegal logging activities with the use of AI. Rainforest Connection, started in 2012 by engineer Topher White, is turning to used handphones to create a real-time monitoring system based on the sounds it captures in order to alert the local community and enforcement agents of when such logging activities are carried out.

Rainforest Connection founder Topher White (in white) up in the forest canopy installing one of its re-purposed used Android phones and, through such devices, detect noises like chainsaws to detect illegal logging activities. (Photo: Facebook/Rainforest Connection)

Mr White combines used smartphones with solar panels to create an always-on beacon – called “Guardians” – that are embedded in tree canopies to collect the sounds in a forest. When its platform discerns sounds like chainsaws or trucks on the spectrogram, this would prompt an alert to the relevant authorities or local communities to act on the information.

In the Peruvian area of the Amazon rainforest, for example, the company is working with groups like the Conservation International and local government rangers to test out the sound-based warning system.

Speaking to CNA recently, Mr White shared that he did not expect to work with lawyers there, given that its justice system is “very slow to get a case going” and it usually takes years if at all.

However, it found a lawyer group called the Peruvian Society of Environmental Law or SPDA, that has the trust of the local community. Once SPDA receives the alert, of say chainsaw sounds detected, the lawyers would file a case immediately and call the police. Since a case has been filed, the police will have to do something, he said.

At the same time, SPDA will also call the local defenders on the ground to stop these illegal loggers and hold them till the police reach the scene, he added.

This is where the human element plays a crucial role of what could otherwise be seen as a lofty tech solution for a real world problem. For every partner Rainforest Connection works with, it usually starts off with a rejection.

Mr White shared that while these partners start off sincere in wanting to use the alerts, they can become unresponsive when he and his team are on the ground working on the deployment.

“A lot of times they can be very sincere, but in the moment, it’s really dangerous and scary work, especially if they are not (teamed up with) para-military.”

The key, he later realised, is when the local defenders know what to do after they stop the immediate illegal logging activities.

“What we realised that when the people (local defenders) know that they are only having to hold these loggers for like two or three hours, or whatever it is, they are far more confident,” Mr White shared.

“It never occurred to me that one of the things holding them back (from making use of our alerts) could be: ‘What do we do next?’ So trying to understand the social pressures and elements and how these overlap, that’s pretty important for us.”

HUMANS MUST EVOLVE TOO

For Massachusetts Institute of Technology (MIT) professor Tonio Buonassisi, removing the human element from the use of AI is akin to the story idea he would tell if he was given an opportunity to direct an episode of Black Mirror, a science fiction TV series with a generally dystopian take on high-tech innovations like AI.

Using another sci-fi series Stargate as his inspiration, Associate Professor Buonassisi said his story would feature a civilisation that stopped thinking for themselves and relied solely on technology as a form of collective memory and decision-making. While this system has its short-term advantages, the lack of diversity in thought would prove to be a challenge too, he revealed in an email interview.

“I’m a big believer that the human spirit must evolve together with technology — that we must continue investing in our own personal growth, so we can continue to direct technology development in ways that are societally beneficial,” said the professor, who is also a principal investigator at the Singapore-MIT Alliance for Research and Technology (SMART).

He shared how a former MIT president was at a crossroads in terms of whether the school would pursue bioengineering despite its potential for misuse. In the end, he decided to go ahead as the then-president reasoned that more than 99 per cent of people are good and will use the technology in the same spirit. They then have to invest in these people to guard against those who might misuse it, said Assoc Prof Buonassisi.

“The same applies now for the development of AI. We must continue investing in education to make sure everyone has access to the means to learn about AI, what it is capable of and its potential,” he said.

“We are more likely to harness peoples’ creativity to solve societal problems faster than ever before, when everyone shares a common knowledge of how they can create change.”

Perhaps the day Mdm Masako can put her legs up and let a machine sort out the thousands of cucumbers daily is coming sooner than expected.