SINGAPORE: In February 2001, a joint venture of Keppel Offshore & Marine (Keppel O&M) in Brazil snagged a US$75 million (S$99.6 million) contract to convert an aging tanker into an offshore production centre.

The floating production storage and offloading facility (FPSO) would be deployed for oil and gas production at Caratinga, a deep-water oil field located northeast of Rio de Janeiro.

The contract, awarded by a Brazilian subsidiary of US engineering company KBR Inc, was a win for the young joint venture formed by Keppel FELS, which was later merged into Keppel O&M, and Brazil’s PEM Setal Group.

Called the P-48, it was the “largest” FPSO conversion project undertaken in Brazil then and its delivery in 2004 marked a “milestone” for Keppel O&M’s operations in the South American country, said former CEO and chairman Choo Chiau Beng in a stakeholders report.

There was, however, a darker side to the story.

Between June 2001 and April 2002, Keppel O&M paid bribes in installments to Brazilian government officials who had helped “put pressure for the (P-48 project) to be carried out”, according to court documents released last month by the US Department of Justice (DOJ).

Emails between Keppel O&M’s executives, a financial controller at its subsidiary and a joint venture partner contained instructions for money to be paid to “some governmental guy(s)”, and later referred to as “friends”, who said “it was definitely with their help that the conversion landed up in Brazil”.

When the email authorising the last installment of US$50,000 was sent on April 4, 2002, a total of US$300,000 in corrupt payments had been made for the P-48 contract.

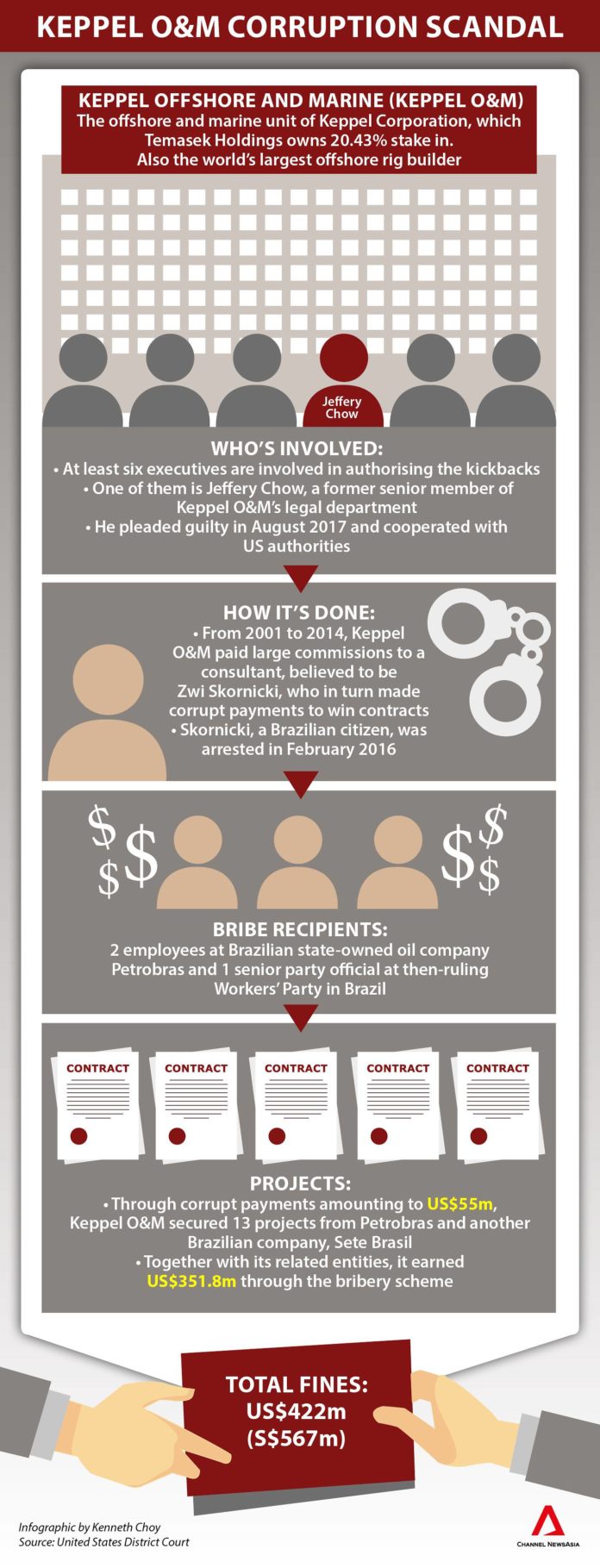

That marked Keppel O&M’s first bribe-for-contract payment in Brazil and by 2014, the bribes had snowballed into US$55 million for the inking of another 12 deals with Brazilian state-owned Petrobras and Sete Brasil.

As part of its modus operandi, millions of dollars in bribes were disguised as large commissions to a consultant in Brazil under legitimate consulting agreements. This consultant is believed to be Mr Zwi Skornicki, Keppel’s former agent in Brazil who was arrested in February 2016.

These illicit payments, made to bank accounts in and out of the US under the names of shell companies controlled by Mr Skornicki, were then transferred to bank accounts elsewhere and into the pockets of company officials and politicians at the then-governing Workers’ Party in Brazil.

For its dirty deal-making over 13 years, Keppel O&M, a unit of local conglomerate Keppel Corporation which state investment firm Temasek Holdings holds a 20.43 per cent stake in, was slapped with a hefty fine of US$422 million as part of a global resolution with authorities in three countries.

This was a penalty harsher than the Keppel unit would have received under Singapore’s Prevention of Corruption Act, said Senior Minister of State for Finance and Law Indranee Rajah in Parliament this week.

In response to the flurry of questions from Members of Parliament (MPs) during the first Parliament sitting of the year, Ms Indranee emphasised that Keppel O&M did not get off lightly for its involvement in the international corruption case.

The Attorney-General’s Chambers (AGC) has also sought assistance for evidence from authorities in other jurisdictions for local investigations to move “as expeditiously as possible”.

THE RISE OF WORLD’S LARGEST RIG BUILDER

Headquartered in Singapore, Keppel O&M was incorporated in 2002 through the integration of offshore rig builder Keppel FELS, vessel repairer Keppel Shipyard and specialised shipbuilder Keppel Singmarine.

The formation of the new Keppel unit was aimed at drawing the “synergies and collective strengths of its yards and offices worldwide”, and “end in-fighting and competing against each other”. “To become a truly global company, we would have to forge a unified team,” Mr Choo was quoted as saying.

And become a global player it did.

Through acquisitions and partnerships with governments and businesses, Keppel O&M has since built up a network of 20 yards in the Asia Pacific, Gulf of Mexico, Brazil, the Caspian Sea, the Middle East and the North Sea regions. It also has a stable of engineering and technology centres in countries, including Bulgaria and China.

Keppel O&M has been the biggest cash cow of its parent company, typically contributing about two-thirds of group revenue, until recent years when plunging oil prices hammered profits at the world’s largest rig builder.

It operated at break-even profitability for the third quarter, while revenue for the three months to Sep 30 dropped 26 per cent to S$380 million on lesser work volumes and the deferment of projects.

Keppel O&M also witnessed a change in leadership in 2017, with Mr Chris Ong taking over Mr Chow Yew Yuen as its chief executive. Prior to this, Mr Ong, 42, was the managing director of Keppel FELS.

“STRONG NEXUS” WITH BRAZIL

The Keppel unit’s relationship with Brazil dates back to the 1980s when it took on various vessel repair and conversion jobs from Petrobras.

In 2000, Keppel FELS formed a 60:40 joint venture with Brazil’s PEM Setal Group to grab a bigger slice of the Brazilian market.

Within a year, FELS Setal secured US$120 million worth of contracts and began running its shipyard in Angra Dos Reis, said an April 2001 media release.

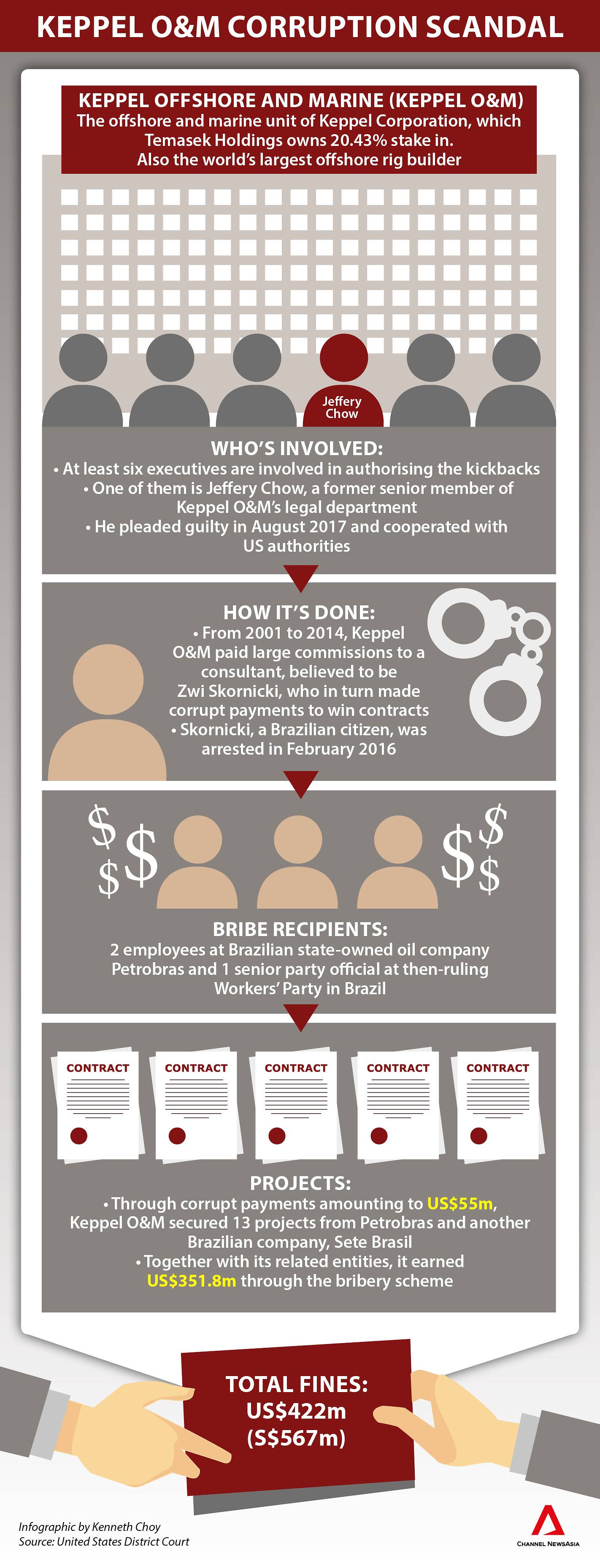

The P-51 project, a semi-submersible production platform used in Petrobras’ Marlim Sul oil field, was one of the 13 deals that Keppel O&M won through the bribery scheme. (Photo: Keppel O&M)

Its activities in Brazil expanded alongside the rise in the South American country’s profile as an important oil and gas (O&G) market, following the discovery of large oil reserves off the coast of Rio de Janeiro in the 2000s.

Riding on this tide of growth in Brazil, Keppel O&M saw strong growth and along the way, began differentiating itself by moving up the value chain to produce higher-value customised rigs fit for harsh sea environments, industry experts told Channel NewsAsia.

By 2012, the Keppel unit had delivered some 20 major projects, including floating production units (FPUs), drilling rigs, FPSO units and drillships in Brazil.

According to IHS Markit’s analyst Ang Dingli, Brazil accounted for the majority of Keppel O&M’s higher value projects.

“Brazilian projects have definitely contributed much to Keppel’s order book given that each Brazilian project was typically of higher contract value than the smaller conversions that Keppel mostly secured in Asia,” he said.

Underscoring Brazil’s status as one of its key markets, a 10-year anniversary supplement published in 2012 said the company is “anchored in Brazil” and has developed a “strong nexus” with the country.

Even as Brazil’s O&G sector took a hit from a double whammy of political woes and plummeting oil prices, Keppel O&M said in its 2016 stakeholder report that the country “is expected to remain as an important oil and gas market in the long-term”.

Apart from the country’s vast offshore oil and gas reserves, other positive factors include “significant funds for Exploration & Production (E&P) investments” from Petrobras and the intention of foreign oil majors, such as Shell, Total and Statoil, to increase their investments in Brazil.

The Brazilian government also had flattering words for Keppel O&M.

Speaking at the naming of the P-56 project, which was a US$1.2 billion contract clinched by a Keppel-led consortium to build a semi-submersible FPU for a Petrobras subsidiary, then-Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff said: “We have proven that it is possible to build rigs, platforms and equipment for offshore exploration in Brazil.”

“We shall count on the partnership of companies which come from far away, such as that of Keppel FELS that comes from Singapore… They know that if they come to Brazil, they will have the guarantee of a demand from Petrobras,” she was quoted as saying in Keppel O&M’s 10-year anniversary supplement.

Former Brazilian President Dilma Rousseff (centre) seen at the naming of P-56 in June 2011 with Keppel O&M’s top managers, such as former CEO Chow Yew Yuen (left). (Photo: 10th Anniversary Special Supplement in Upstream)

But stiff competition for projects may have forced the company to find any edge possible to secure a deal.

According to the US court documents, Keppel O&M made corrupt payments to obtain the 13 contracts even when concerns of running afoul with the law surfaced – as seen in the emails for the P-61 project.

The US$1 billion contract, awarded in 2010 to an equal joint venture between Keppel FELS and US engineering firm J. Ray McDermott, involved the building and operating of the P-61 Tension Leg Wellhead Platform (TLWP) in the Papa-Terra field located in Brazil’s Campos Basin.

Apart from being a boost in its order book, the project would help Keppel O&M to establish a “stronger presence” in a niche product area like the TWP, said OCBC analyst Low Pei Han.

Work to obtain the large platform construction contract from Petrobras began in 2007 but in March, a joint venture manager had expressed concerns about retaining Mr Skornicki for the project because “under the joint venture partner’s corporate governance rules it cannot pay (Consultant) to pay government officials”.

An email from Keppel O&M’s executives in April said that if they are “so hand tied to the US Code of Business Conduct, it would not be possible to involve (Consultant) which in reality diminishes our chances in the project.”

In 2008, following several discussions about limiting the scope of Mr Skornicki’s consulting services and bribery concerns expressed by the joint venture partner, an email from a Keppel O&M executive reiterated the need for “fees” to be made.

“(Consultant) also mentioned that (the joint venture) was not originally invited for this project until much lobbying with his friends help. And the fees were told to us sometime ago. If they perceive us as not honouring our commitment, it may be bad for future business,” DOJ’s documents showed.

In 2009, executives from Keppel O&M authorised the payment of bribes equal to a percentage of the P-61’s contract value to a Brazilian official and the country’s then-ruling Workers’ Party. The illicit payment totalled US$8.8 million.

A Keppel-J. Ray joint venture secured Brazil’s P-61 TLWP contract worth about US$1 billion in February 2010. (Photo: Keppel O&M)

OVERHAUL OF CORPORATE CULTURE NEEDED

Despite the high-profile corruption scandal, industry experts believe that Brazil remains a key market for Keppel O&M given the country’s abundance of deep-sea oil and gas reserves.

Singaporean rig builders also remain best positioned to land upstream oil and gas contracts with their experience and expertise.

But to avoid falling into the murky waters of corruption again, it will need a comprehensive revamp of the organisation, said Mr Toru Yoshikawa, professor of strategic management at the Singapore Management University’s (SMU) Lee Kong Chian School of Business.

Citing how Keppel Shipyard was also charged with corruption more than 20 years ago, Prof. Yoshikawa noted that an overhaul of both the board and corporate culture will be necessary.

“A change in people does not mean that this will never happen in the future so there needs to be a change in the system.”

According to the Corrupt Practices Investigation Bureau (CPIB), Keppel Shipyard was charged in 1997 for giving bribes to secure business deals overseas.

For one, Prof. Yoshikawa raised the example of implementing a whistleblowing policy that would encourage and protect employees who speak up about malpractice in the company.

These changes will also have to be extended to its subsidiaries overseas, he added.

As part of its Deferred Prosecution Agreement (DPA) with US authorities, Keppel O&M has had to take on “extensive remedial measures”.

Those included disciplinary action against 17 former or current employees which led to seven employees departing the company; demotions and/or written warnings to seven employees; approximately US$8.9 million in financial sanctions on 12 former or current employees; and anti-corruption and compliance training for six employees.

Keppel’s spokesperson said the company has “moved quickly” to strengthen its regulatory compliance measures and has rolled out an enhanced programme across the group.

Specific measures include an enhanced code of conduct containing detailed anti-corruption provisions and guidance on dealing with intermediaries.

Amid questions raised by corporate governance experts about the efficacy of its auditing and internal governance, the spokesperson responded to queries on Jan 5 that the current boards of directors of Keppel Corp and Keppel O&M “were not aware of the illegal payments” made in Brazil.

The illegal payments were “deliberately concealed by those complicit in the bribery and structured as agency fees”.

“The agency fees were not approved by the Boards of Keppel Corporation or KOM as they were built into the contract values of the respective projects and bidding for projects is in the ordinary course of KOM’s business,” the spokesperson added.

While it is possible for the board to be unaware of the unclean deals, Prof. Yoshikawa suggested the set-up of an independent department within the company moving forward.

This department will “be neutral and free from any influence” as it provides information about the company to board members.

Such “actionable” plans will be crucial as Keppel O&M seeks to recover from the scandal, said the SMU professor.

“Companies usually announce some commitment to make changes following such incidents, but people will be watching at how actionable and implementable these plans are.”