Close the door, shut the windows, set our social media pages to private; we want strangers to butt out when we are caught up in something too nasty to describe with just a sad-face emoji.

When family fights and lovers’ quarrels get heated in the still, humid air of a Singapore night, strangers sometimes cannot help overhearing the squabbles from a nearby block. With family sizes shrinking here, and with fewer relatives to help mediate between loved ones, can we survive the sudden bad fights without the kaypoh-kindness of strangers?

When out and about by ourselves, can we depend on strangers to speak up for us when we are unable to defend ourselves?

Earlier this month, a video of a woman seen railing at a deaf-mute cleaner and his manager was posted online by Facebook user Euphemia Lee. She was at a Jurong East mall’s foodcourt when she witnessed the incident. The Straits Times reported that she said no one intervened as the manager seemed to be handling the situation.

But let’s say if it were just the cleaner facing the angry woman, who was with her husband, would a stranger put down his or her chopsticks and go over there to try to calm things down or look for a supervisor to do so?

The Straits Times reported that the share of households made up of nuclear families has dipped from 56 per cent in 2000 to 49 per cent in 2014. These are two-generation families in which a couple live with parents or children.

At the same time, the share of one-person households and those headed by a married couple who are childless or not living with their children has risen – from one in five in 2000, to one in four in 2014.

American urbanist Joel Kotkin told National Public Radio that the trend “where family is sort of beginning to become maybe a choice, certainly not the normative force” was a very powerful one. He is the primary author of the 2012 report, The Rise of Post-Familialism: Humanity’s Future?, which was published by the Civil Service College, Singapore.

Prof Kotkin, a presidential fellow in urban futures at Chapman University in California, said: “What’s scary is in much of East Asia, in the United States in the future and in Europe, there are no uncles. There are no aunts. And so that whole extended family network, which still exists for the current generation, may not exist in the future…”

So as our aunties and uncles fade out of our lives, will this make us want even more than ever to build a different kind of “family”, a society of kind strangers? Of course, there are good pals and friendly neighbours for us to call on in our time of need, but can we depend on the nearby stranger to quickly respond to the terrified cry in the middle of the night?

When I do hear one of those screams, I think about the possibility of misunderstanding the situation and calling the authorities unnecessarily, I think of the privacy people want, and I think: “I don’t want to be a kaypoh (busybody).”

(I think some diners at the Jurong foodcourt could have hesitated in these ways as they listened to the shrill cries of the angry woman. And then there’s always sheer indifference, which I am way too familiar with because I am horribly, selfishly more interested in looking after myself than anyone else.)

Blood-curdling shrieks one dawn from a neighbour’s home made me stumble towards the door before I fully woke up. A girl’s sudden wails on a different day made me and my hair stand up abruptly. And, in the wee hours during one night, a man yelling at and shoving a lover on the street stopped me in my tracks.

I listened carefully to the neighbour’s cries in case there was a need to call the cops. I looked over to make sure the child wasn’t in difficulties in the pool and that her mum was nearby. I spoke to the guy pushing the woman roughly.

I was okay with being a kaypoh in the neighbour’s case, as it appeared that there were no broken bones, just sadly, a broken heart.

I was not happy with being a kaypoh in the child’s case, as we’ve got to try to give dads and mums some leeway to parent their kids. I observed the mother chatting with another woman as her little girl, wearing a pink float, screamed-sobbed “mummy, mummy” non-stop in the swimming pool.

Perhaps one approach parents take is to let the tiny tornadoes blow up until their fury is spent. When it went on for longer than was bearable for another stranger in the shared space, he called out to them to please do something about it.

There’s a saying, “It takes a village to raise a child”. As the extended family network fades into the past, will future dads and mums think it is a pain if the kampung is kaypoh about something as personal as how their children are raised?

I found the idea of “group reliance” attractive when I read an article by CityLab/The Atlantic magazine last year about how “in Japan, small children take the subway and run errands alone… The kids are as young as six or seven, on their way to and from school, and there is nary a guardian in sight”.

Mr Dwayne Dixon, a cultural anthropologist who wrote his doctoral dissertation on Japanese youth, offered this explanation to The Atlantic: “(Japanese) kids learn early on that, ideally, any member of the community can be called on to serve or help others.”

In the case of where I saw a man shoving a woman, I was tense but okay with being a kaypoh, as I no longer could give them their privacy (on a public street) when he pushed the whimpering woman hard enough for her to stagger backwards.

I asked: “Are you okay?” The man shouted at me: “You call the police, lah!” “What a lovely suggestion,” I thought. The woman later grabbed a cab and left him standing in the street.

I didn’t intend to do some sort of rescue. It was more like a verbal version of first aid until the experts, like the police or social workers, were called in if necessary. I hoped to at least put the escalation of violence on pause.

Meanwhile, another passer-by walked on briskly. I didn’t blame him for doing so. I felt like running away when the man looked daggers at me. I figured that if I sprinted like I had a demon clawing at my back and if I didn’t fall into a longkang, I could make it to a nearby fire station for help in minutes.

In less stressful times, I unkindly shy away from the tough work done by wonderful civic groups and selfless volunteers who tackle social problems. But meaner strangers like me can sometimes resist the urge to run away long enough to offer quick help in the streets.

As we become related by blood to fewer people in the world, can we afford to not build social capital with strangers in our society?

Even if we are still surrounded by family in the real world, when we go online, we operate in a sense as one-person households and are at risk of being bullied in the virtual world. We need kaypoh-kind strangers to step in before the situation blows up, and help pity the trolls together.

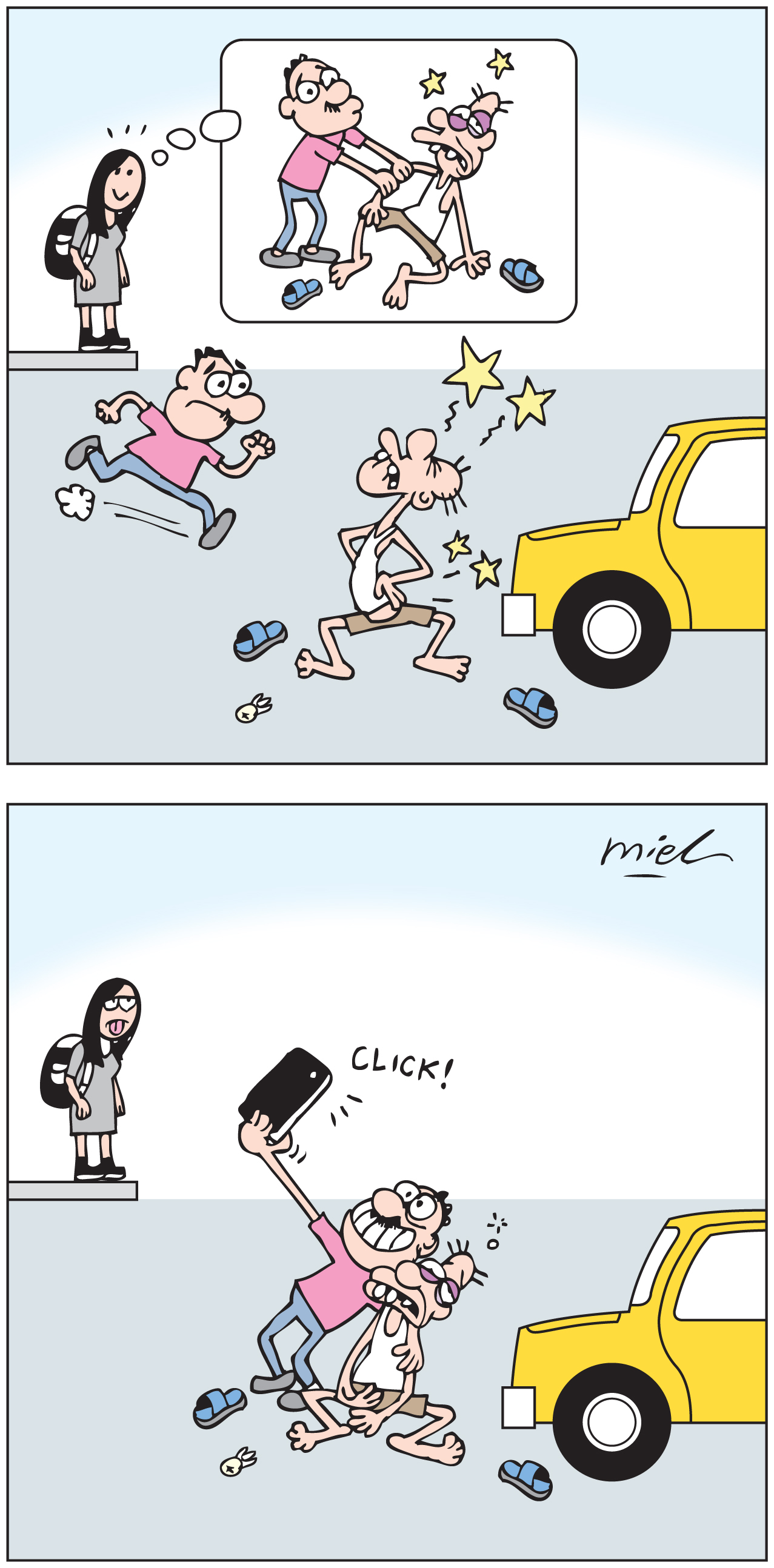

Last week, Ashvin Gunasegaran, 12, was honoured by the Singapore Civil Defence Force for helping car accident victims.

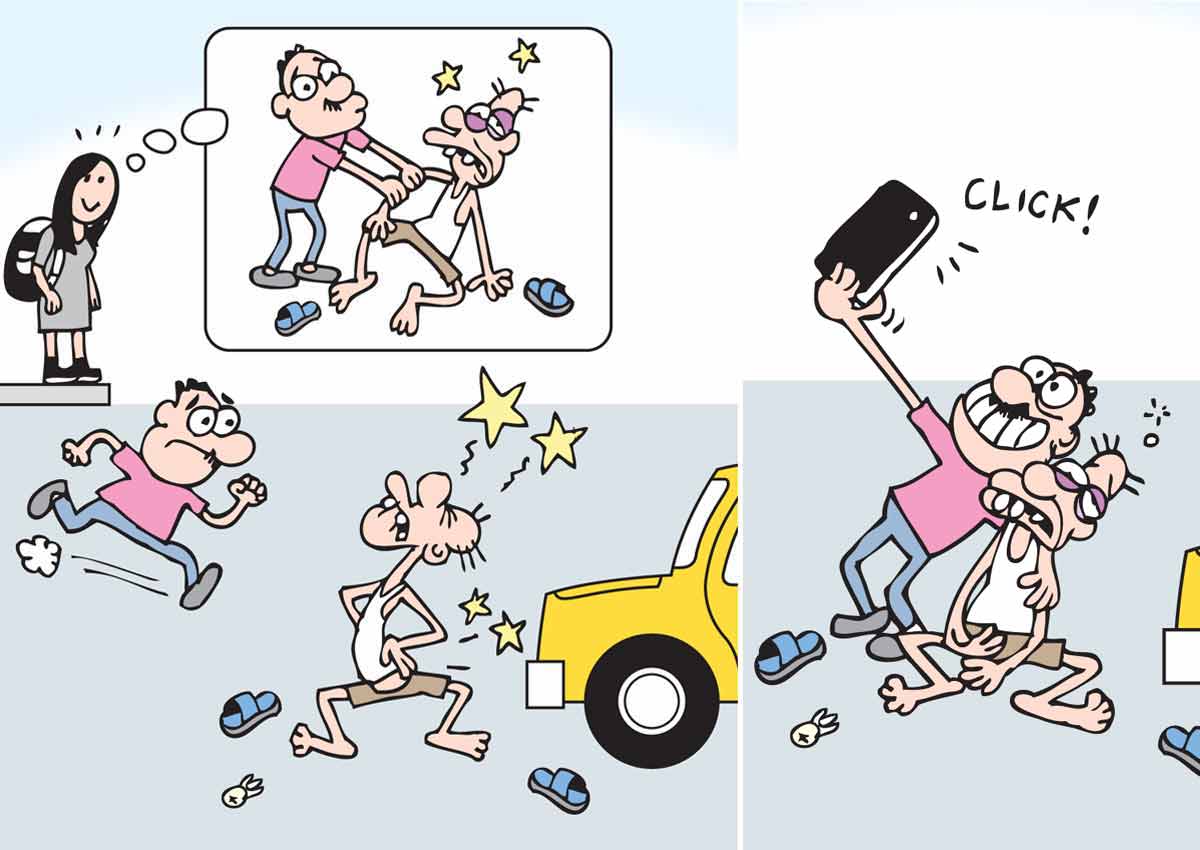

The Straits Times reported that he had rushed to help victims in Yishun because, he said, other passers-by were “too busy taking pictures with their phones instead of helping”.

Now, more than ever, we need to open the door to a kind stranger like him if we want to be stronger.

This article was first published on June 12, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.