It was a clear September day in 2001, and Mr Yap Kwong Weng was sound asleep in the back seat of a red Buick making its way from San Diego to Los Angeles.

In the United States to attend its elite Navy Seals training programme, the then 23-year-old Singapore Armed Forces commando was exhausted. And understandably so, because he had just survived Hell Week, the programme’s most brutal component.

Lasting 51/2 days, it compresses sleep deprivation (recruits sleep no more than four hours during this period), near hypothermia, and other forms of unthinkably harsh mental and physical challenges to weed out all but the toughest warriors. Only 25 per cent of all candidates make it through Hell Week.

Mr Yap’s deep slumber was interrupted most dramatically. The driver had fallen asleep at the wheel; the Buick, which was going at about 130kmh, hit a kerb, flew into the air and flipped over twice before turning turtle on Highway 101.

“There were four people in the car. I was thrown out the rear window. When they found me, I was two or three metres from the car and not breathing because one of my lungs was punctured,” he says.

Rescue workers had to seal off both ends of the highway and airlift Mr Yap – who also had his collarbone and several ribs broken – to Martin Luther King Hospital in Los Angeles.

When he came to 24 hours later in the hospital’s intensive care unit, he had two things on his mind: to see his parents and to go back to his Seals course.

He demanded to speak to his commanding officer at the Naval Special Warfare Training Centre in Coronado, California.

“I said, ‘Sir, this is Lieutenant Yap from Singapore. I got myself in an accident and I am in the hospital, but you are not going to give up on me…”

Against his doctors’ orders, he went back to the course two weeks later. “I had to sign an indemnity form. Fortunately, the rest of the training was mostly skills-based, but there were still runs and timed swims. I took things step by step, day by day, month by month,” says Mr Yap, who graduated from Basic Underwater Demolition/Seal Class 237 on Feb 2, 2002.

The course and Hell Week, he says, were a big game changer in his life. Among other things, it taught him never to give up on himself and on others.

“When people fall, you have to give them the chance to pick themselves up again,” he says.

The experience probably also gave him the mental strength to reimagine a whole new future for himself and figure out his place in the world. He went back to school and got not just a degree, but also a master’s and a PhD. He also left the army to, first, blaze a corporate trail and, now, chart his own entrepreneurial journey in Myanmar.

Determined to find purpose, he has also immersed himself in various projects to fight for inclusion and improve lives, for organisations ranging from the United Nations Association to the Global Dignity Organisation.

“People ask me what I hope to achieve. I don’t know the answer yet, but I do know that every river has its end. I just don’t know where that is yet,” says Mr Yap, now 38.

Even so, he has drifted quite a distance from the source of the river which, in his case, was a two-room flat in Toa Payoh.

The only son of a shipping supervisor and a housewife, he studied at San Shan Primary School and First Toa Payoh Secondary School.

He was a mediocre student but a superb sportsman, excelling in everything from athletics to volleyball.

By the time he was 11, he already had his black belt in taekwondo. The martial arts training came in handy when seven ruffians armed with chains ganged up against him after school one day.

“They accused me of staring at them. It was seven against one and I knew I was going to lose, so I sized up the situation and decided to go for their weakest link – the shortest and fattest boy,” he says.

Mr Yap felled his target with a turning kick to the head and made his escape when the victim’s flustered accomplices attended to him.

The decisiveness is a character trait; once he knows what he wants, he will go all out to get it.

And from a very young age, he had set his sights on being a commando. It was fuelled by his stint as head of his school’s National Cadet Corps (NCC).

“I loved the rituals and the military drills. I was bent on joining the army, and the commandos were the best,” says Mr Yap, who travelled to India and took a parachuting course while he was with the NCC.

After completing his A levels at Jurong Institute, he trained hard and passed the vocational test for potential commando recruits with flying colours.

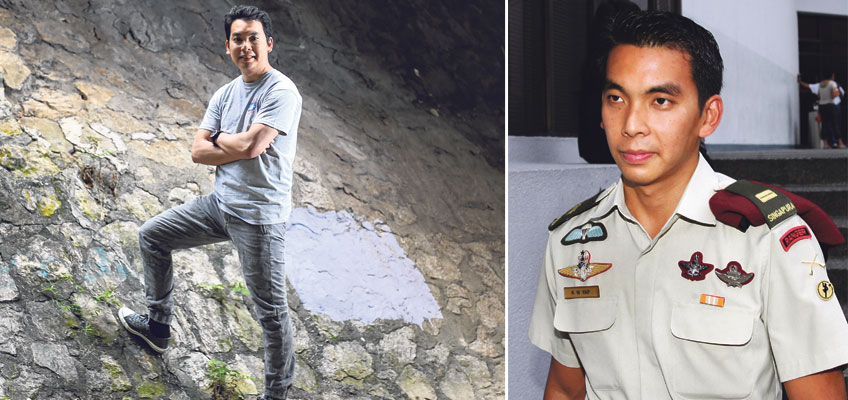

That was how he came to join the 1st Commando Battalion in 1997, where he received gruelling training before receiving his red beret – the symbol for parachute and elite forces around the world.

Because he graduated top of his platoon at Officer Cadet School, the army offered to send him to Sandhurst, the British army’s famous officer training academy in Berkshire, outside London.

He turned down the offer, he lets on sheepishly, because he did not want to be away from his childhood sweetheart for 18 months.

“I thought she was the person I would end up with,” he says, adding that the relationship eventually did not work out. “To be honest, I regretted that decision.”

Instead, the second-lieutenant went to Ranger School where, for 65 days, he underwent brutal training and learnt things – both good and bad – about himself.

“You discover your strengths, but you also find out if you will give in to greed, betrayal…”

Mr Yap was then deployed as a platoon commander with 30 experienced soldiers under his charge.

Over the next few years, he went on several overseas missions before being nominated for the renowned US Navy Seals programme, which includes rigorous training in direct action warfare, special reconnaissance and counter-terrorism.

His parents, he says, cried when he insisted on completing the programme after his accident.

“They said I was mad, especially since I had nearly died. But I could not fail my country. If I had to crawl back, I would.”

The experience changed him. Although his military career was going smoothly, he decided he needed a formal tertiary education.

Some of his friends told him not to bother, but his mother sold off some of her jewellery so that he could take a leave of absence from the army and pursue a degree in communications at the State University of New York at Buffalo .

The formal education changed his perspectives on life.

He knew he had the brawn, but he realised it was also time to develop and expand his brain.

After graduation, he took on a leadership development role at the Commando Training Institute before moving on to Mindef, where he became a senior defence analyst.

Among other things, he looked at terrorism threats and worked on counter-terrorism situations. He also wrote and edited a monograph on the special forces, and authored several papers and articles on topics ranging from battle systems to military leadership and crisis management.

Not content with his basic degree, he went on to obtain a Master of Public Administration at the Lee Kuan Yew School of Public Policy and a PhD from the University of Glasgow.

In 2012, the National University of Singapore gave him a Distinguished Leadership Award.

“Not bad, from a school which rejected me three times,” he says with a smug grin.

Mr Yap, who got married to a civil servant in 2008, says he was trying not just to make sense of life, but also to make full use of it.

“As a defence analyst, I was making sense of the world by day. At night, I would go to my classes trying to learn more about the world,” he says.

As if that was not enough, he spent his weekends on community work. He started out volunteering at welfare group AWWA, helping to distribute food to old folks’ homes and disadvantaged families in Ang Mo Kio and Choa Chu Kang.

“When you volunteer, everyone benefits,” he says simply.

Mr Wan Tapern, 38, has known Mr Yap since their NCC days.

Says the Changi Airport senior manager: “He has not changed. He does not waver, and he does not waste time. Once he has set his mind on something, he will do it.

“But his commitment to help the community is a pleasant surprise. I guess it developed along the way as he became more exposed to the world. I am very happy to see this side of

him growing.”

Mr Yap went on to become the secretary-general of the United Nations Association and Singapore’s first Rotary Peace Fellow, and was also named a Young Global Leader by the World Economic Forum (WEF).

In 2011, he went on a punishing 100km trek in China’s Taklamakan Desert to raise awareness in Singapore of the UN’s millennium goals.

The world became his oyster.

“As a WEF young global leader, I got to spend a week in Harvard learning about world issues from people like General John Allen,” he says, referring to the four-star general and former commander of the US forces in Afghanistan.

Says Mr Dan Tan, a former commando-turned-healthcare counsellor who knew Mr Yap during their training: “It is part of Kwong Weng’s DNA. He is really into upgrading skills, learning new things and taking on new challenges.”

A leap into the corporate world seemed inevitable for Mr Yap, who was a senior captain when he made the decision in 2012.

It was not easy. Over three months, he sent out nearly 60 application letters but received no replies. But just when he was starting to get discouraged, the offers came.

True to his adventurous spirit, he accepted an offer from offshore firm Jebsen & Jessen to work in Myanmar. As its deputy general manager, his job was to develop business in the country and open new markets in Laos.

Next came a stint as chief operating officer of the Parami Energy Group, where he worked to ensure transparency in the group’s policies and practices.

Last year, he struck out on his own and set up Leap, which specialises in trading , distribution and construction.

Myanmar, he says, is a country in the throes of change.

“The opportunities are there, but you have to sort out a lot of obstacles. There are those who choose the easy way out, but I believe in getting a competitive edge in the right ways,” says Mr Yap, whose company has won several tenders to build living quarters for civil servants.

“It can be done. The Singapore brand is strong; we are known for our efficiency and credibility.”

His latest baby is a book, also called Leap, about his life and his experiences, published by Marshall Cavendish .

“I want Singaporeans to know that no path is too difficult and that the world is waiting for us to explore,” he says. “Singapore is a good place, but we need more innovation, entrepreneurial spirit and the derring-do to try new things. You will fail at times, but you will stand up and go again.”

Just like he did.

kimhoh@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on May 15, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.