SINGAPORE: During Chinese New Year last year, retiree Kenneth Tang wanted to visit his sister-in-law at her home in Upper Bukit Timah, in a relatively secluded area he was unfamiliar with.

Instead of getting driving directions with a few taps of his smartphone, the 64-year-old sat in his living room, put on his reading glasses and studied the route on the pages of his 2018 street directory.

“I think GPS is more convenient and better in many ways, but I use road directories because I can have a better idea of how to get to the place I am going to,” he told CNA.

Mr Tang said the directory allows for more flexible alternative route planning in the event of congestion, and gives a clearer picture of nearby car parks – crucial for peak times when every lot has been snapped up.

“I use road directories also because I have been using it for years, long before GPS was available,” he added. “My friends and I who are from the older generation have been dependent on them.”

Mr Tang is not alone. Some people argue that street directories are more up-to-date and safer to use than online maps. They can also show a bigger picture and more detail than their virtual counterparts.

This detail includes address numbers, building occupants, as well as future developments and roads, said Amarjeet Singh, publishing manager at Mighty Minds, currently the sole producer of local street directories.

“Malaysian delivery drivers like this very much,” the 61-year-old told CNA at his office in Toa Payoh. “Because they do a lot of deliveries to industrial areas.”

Besides logistics workers, Mr Singh said other customers include Government agencies like the police and civil defence, and property agents who market homes to potential clients by showing nearby amenities.

DWINDLING DEMAND

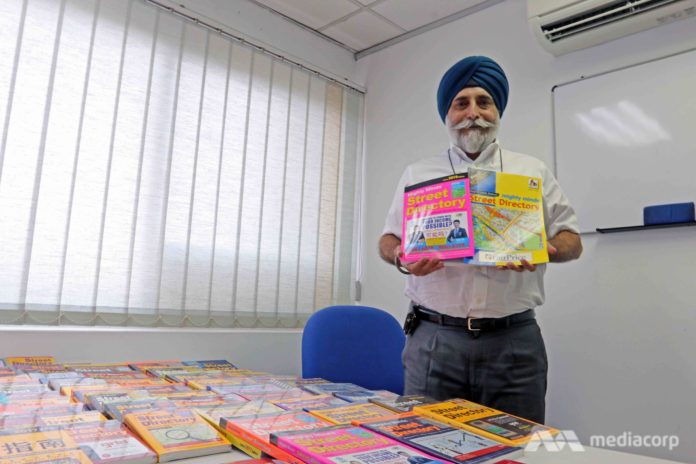

But the numbers don’t lie. With the advent of GPS and online maps, Mr Singh admitted that circulation has gone down. The company, which produced its first edition in 2000, used to distribute about 100,000 copies every year. Now the figure hovers around 30,000.

Mr Amarjeet Singh holding the 2019 (left) and 2000 Mighty Minds street directories, the newest and oldest editions in the series. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Mapping consultant Mok Ly Yng told CNA that web-based maps started to appear in the late 90s, allowing the tech-savvy younger generation to go online for directions. “I think it’s the demographic and exposure,” the 51-year-old said. “You don’t use these kind of paperbacks already.”

He said that even cabbies, previously one of the largest users of street directories, have stopped using them. “Every time I take a taxi, I will ask if they have a street directory,” he added. “They would have to think when was the last time they bought one.”

Mr Mok Ly Yng with a 1954 map of Singapore, used to create the “new series” of street directories. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Mr Mok, who has been researching Singapore maps for more than a decade, is “very sad” about this. While street directories are growing less relevant as navigational tools, outdated versions help chart Singapore’s constantly evolving landscape.

“It’s a rare resource,” he said, noting that they keep track of changes in the streets and buildings of Singapore. “You get to see updates in our terrain and landscape.”

FIRST-EVER STREET DIRECTORY

This is especially as street directories go back to the pre-war days of 1936, when the British government published the first ever Singapore Gazetteer.

Cover page of the 1936 Singapore Gazetteer, the first ever official street directory produced. (Photo: Mok Ly Yng)

The hardcover contained a simple road index and two attached maps: One of Singapore and another of its town centre. While the first map only showed major roads and a few rural areas, the second was sufficiently detailed, with different colour schemes for parks, buildings and water features.

The town map attached to the 1936 gazetteer. (Photo: Mok Ly Yng)

These directories were in high demand, Mr Mok said, given that Singapore was already at the time a “very famous” tourist destination. The island stood on the trading route for ships heading to the other British colonies of Australia and New Zealand.

“People would have nothing to do as their ships were reloaded with fuel and food,” he added. “So, they would go out and wander around.”

The Singapore map attached to the 1936 gazetteer. (Photo: Mok Ly Yng)

When the war came, officials were ordered to burn the directories so the Japanese could not use them. And by the time the war ended, years of changes to Singapore’s landscape had gone unrecorded.

1936 vs 2019: The red line indicates where the coastline would have been. (Photo: Mok Ly Yng, Google Maps)

So in 1950, the British government commissioned new land and air surveys for a fresh set of maps and directories. Previous editions were produced only using land surveys.

The 1950 street directory was the first produced in the post-war era. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

In the meantime, the cash-strapped government revived the old series of street directories, scrimping on costs by printing maps stripped down to mere outlines.

The 1950 edition, which contains a sparse town map, was when postal districts were first introduced. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

THE NEW SERIES

After completing the surveys in 1954, the government finally printed the new set of standalone maps. These flew off the shelves like hotcakes, Mr Mok said. People used them to travel and start businesses as motor cars gained popularity and trade restrictions were lifted.

“Chinese companies also bought licenses to reprint government maps for tourist use,” he added.

The highly detailed 1954 Singapore map was so big it had to be divided into multiple sections. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

When the government realised the demand for a steady stream of up-to-date maps, it made them the main feature of the street directory, instead of attaching them at the back as usual.

This was when the modern street directory known today was born: In atlas format with pages of cross-sectional maps.

The 1954 street directory was the first to use cross-sectional maps. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

As the maps were divided into pages, workers would also find it less daunting to update and redraw them after daily trips to the ground noting changes to buildings and streets. This process takes a much shorter time than the more accurate land and air surveys, which use proper equipment to produce high-grade topographical maps.

Mr Mok said the simplified process was good enough for street directories, as they were used for simple navigation without the need for extremely accurate positions and distances.

The 1954 edition also had a section dedicated to bus routes (right), with services from different companies going as far as Johor. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

As expected, the “new series” of street directories – which included short write-ups of tourist attractions and postal box locations – was a hit. Records show that the first edition was reprinted twice in four months.

A NEW CHALLENGER

As the years went by, the government introduced new features in street directories, including one-way traffic maps in 1961, luminous orange colour schemes in 1973, and blue ink and metric scales in 1975.

The first edition Mighty Minds street directory contained a large, pull-out Singapore map and had a slim design “for fast and easy reach”. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

In 2000, Mighty Minds entered the market with its own version of the street directory, based off a Singapore map it had bought from an Irish company. “We thought there was a big market,” Mr Singh said. “We could do a better job and become the market leaders.”

And indeed it did.

The Government stopped producing street directories in 2009, with industry players citing reasons like dwindling demand and digitisation. Mighty Minds stuck with its product, coming up with pocket editions that could fit in handbags and delivery pouches, and A3-size editions for people who could not see clearly.

Mr Amarjeet Singh has been at Mighty Minds since it was formed in 1988 as a publisher of children’s books. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Mr Singh said his team is constantly finding new ways to make it quicker and easier for users to find places and navigate routes. The newer editions include a coloured street index, bus stop numbers and zoomed-in insets for major junctions.

On the technological front, the team uses software that can automatically cut a map into pages based on a specific scale, and a machine that logs in geocodes when workers on the ground record changes in street or building data.

Mr Mok said the latter process of updating information has remained largely the same over the years. “You can’t run away,” Mr Singh added. “You have to do the legwork.”

EXHAUSTING BUT REWARDING

At Mighty Minds, this updating of information is done by two teams of two surveyors almost every day. They will spend a few days covering each page of the street directory, with the aim of surveying the whole of Singapore at least once a year.

Work involves driving through every road, physically looking out and ensuring that every bit of information – road names, block numbers, building occupants – on the page is up to date. Changes are logged into a system together with their geocodes.

“In Singapore, people change names like changing clothes,” said Tee Singh, 62, a surveyor who has worked with Mighty Minds for more than 20 years.

In the Mighty Minds 2007/2008 street directory, this enlarged map of the Central Business District clearly indicates building occupants. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

Mr Tee said the day usually starts anywhere between 6am to 8am and runs till 11.30am. Then it’s lunch before work resumes at 2pm till 4pm. This is so surveyors can avoid the traffic, especially as they often need to stop the car.

For heavily congested areas like industrial estates and the Central Business District, weekends and public holidays are their best bet.

“It’s quite interesting and challenging,” Mr Tee added of his job. “Life is not boring.”

In the 2007/2008 edition, the page on the new estate of Punggol shows upcoming roads in light shadings and future developments like a proposed town centre. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

This is because it’s not just a case of sitting in a car. In areas with heavy development like Bayshore, Tengah and Bidadari, Mr Tee will visit construction sites as soon as they pop up to get information on future roads and developments.

There, he will try speaking to contractors and studying their maps to find out what roads and buildings are coming up. If they decline to give details, he would have to “go in deeper” and check the signs put up there for names and contact numbers.

“There’s a whole list of 10 to 15 people,” he said. “You call all, somebody, somewhere will give you that information.”

Mr Tee said he’s visited almost every condominium showroom in Singapore to include upcoming condos in the street directory. He’s walked all of the new Jurong Lake Gardens to see how the roads and paths there have changed. He’s driven in circles around Jewel Changi Airport for almost a day just to find the new drop-off point.

“Our business is about giving people the information before they can get it from anywhere else,” he added.

The work does not stop there. Back at the office, Mr Tee will go online to cross-check the updated information. This could involve searching for contact numbers and calling businesses to verify if they’re really occupying a building.

Mighty Minds has billed its street directories as the “most updated”, even in the age of highly mobile online maps. (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

While Mr Tee acknowledged that his job is exhausting, he thoroughly enjoys it. He was a serious runner and he’s always dressed in cotton clothes and comfortable shoes, so the physical part doesn’t faze him.

“What makes me happy is that we dare to write that we are the most updated street directory,” he said, adding that some online maps contain data that’s more than three years old. “Everybody says oh, just use GPS, but the information is not up to date.”

Mighty Minds publisher Mr Singh said drivers should still pick street directories over online maps for reasons of safety.

“People are spending their time looking at their GPS device rather than focusing on the road,” he said, pointing out that delayed instructions could cause drivers to swerve or brake abruptly and lead to accidents. “I call these drivers GPS robots.”

Regardless, Mr Singh said he’ll never stop producing street directories, noting that they’re still used as course material for taxi and private hire drivers in Singapore. “The figures have reduced, but it won’t go obsolete,” he stated.

FROM STREET DIRECTORY TO AUGMENTED REALITY

But keeping things relevant comes at a cost.

Labour, printing and rental fees have all gone up, Mr Singh said, meaning Mighty Minds’ latest edition street directory costs S$16.90, compared to its first edition price of S$4.90. “All that has to come from somewhere,” he added. “We have no choice but to pass it on to the consumer.”

Despite the rise of online maps, Mr Amarjeet Singh has never thought of giving up on street directories. “There are very few players who can do mapping,” he said. “It’s a specialty subject.” (Photo: Aqil Haziq Mahmud)

As production costs for older products keep increasing, mapping consultant Mr Mok believes the future of street directories lies in augmented reality. This includes glasses that visually tunnel through structures to give users directions in real time.

“That’s how street directories will evolve,” Mr Mok said. “Google Glass was a viable thing, but it was too advanced for its time. It will come back, in another form maybe.”

Google has already introduced augmented reality for its maps app. (Photo: Mark Brooks)

Mr Mok pointed out that the technology already exists, noting that it was only a matter of ironing out issues like cost, comfort and speed of connectivity. “If people don’t like the design, that’s it,” he said. “So, it’s hard to predict very accurately in terms of the trajectory of technology and the adoption by humans.”

Nevertheless, Mr Mok said the mapping industry, despite never being at the forefront of cutting-edge technology, has always evolved by “assimilating” different advancements.

“This is a tradition in mapping,” he added. “Mapping is not a leader in technology, but it adopts many leading technologies to make it work.”

(Readers who want to see how their neighbourhood used to look on a map of 1966 compared with a more contemporary version can click here.)