KIKI SIREGAR BENGKALA, Indonesia – Balinese women dressed in gold bodices dance to rhythmic drumming while waving fans as men in purple outfits sit cross legged around them, jiggling their arms and chanting.

It appears to be just another show on the Indonesian resort island, known for its ancient culture and rituals, but there is a key difference – the dancers are all deaf and cannot hear the beat.

They perform the moves, learnt over months of hard training, from memory.

The village of Bengkala has been home to an unusually large number of deaf people for generations, and nowadays about 40 out of its approximately 3000 residents have severe hearing loss.

But unlike in other parts of Indonesia where they could face mistreatment, local people have taken the deaf residents to their hearts. In many ways, life in the small hamlet has come to revolve around them.

As well as the dance project, a unique sign language called Kata Kolok has been developed in the isolated village which has been mastered by those with hearing impairment, as well as many of those who can hear, prompting interest from scientists around the world.

In addition, deaf villagers are trained in skills such as making handicrafts that can be sold in the heaving tourist resorts of the island, and they work side by side with other villagers in the rice fields.

Photo: AFP

“Human rights are the same everywhere. So I thought, why should the deaf be ostracised?” said Ketut Kanta, who heads a community group for the village’s deaf residents.

The approach is relatively unique in Indonesia, where the disabled often suffer harsh discrimination.

Bengkala, in northern Bali, has existed for about eight centuries.

Residents often scrape a living tending to the surrounding rice fields and education levels are generally low.

In the past villagers thought the high incidence of deafness was due to a curse but those superstitions – and the prejudices they created – have largely been abandoned after experts concluded it was due to a recessive gene common among the local population.

It was not until the 1960s that the village began to make efforts to better integrate its deaf residents and nowadays everyone is treated equally, according to village head I Made Arpana.

“We don’t differentiate between deaf villagers and non-deaf villagers,” he said, adding that the community did not want the hard of hearing residents to feel “inferior”.

A key factor in creating this peaceful co-existence has been Kata Kolok, which literally translates as “talk of the deaf”, and is used to varying degrees by around 80 per cent of the villagers.

It is different to international and Indonesian sign language. It has grown organically over the decades and has its own unique signs created by villagers to reflect how they see the world.

Photo: AFP

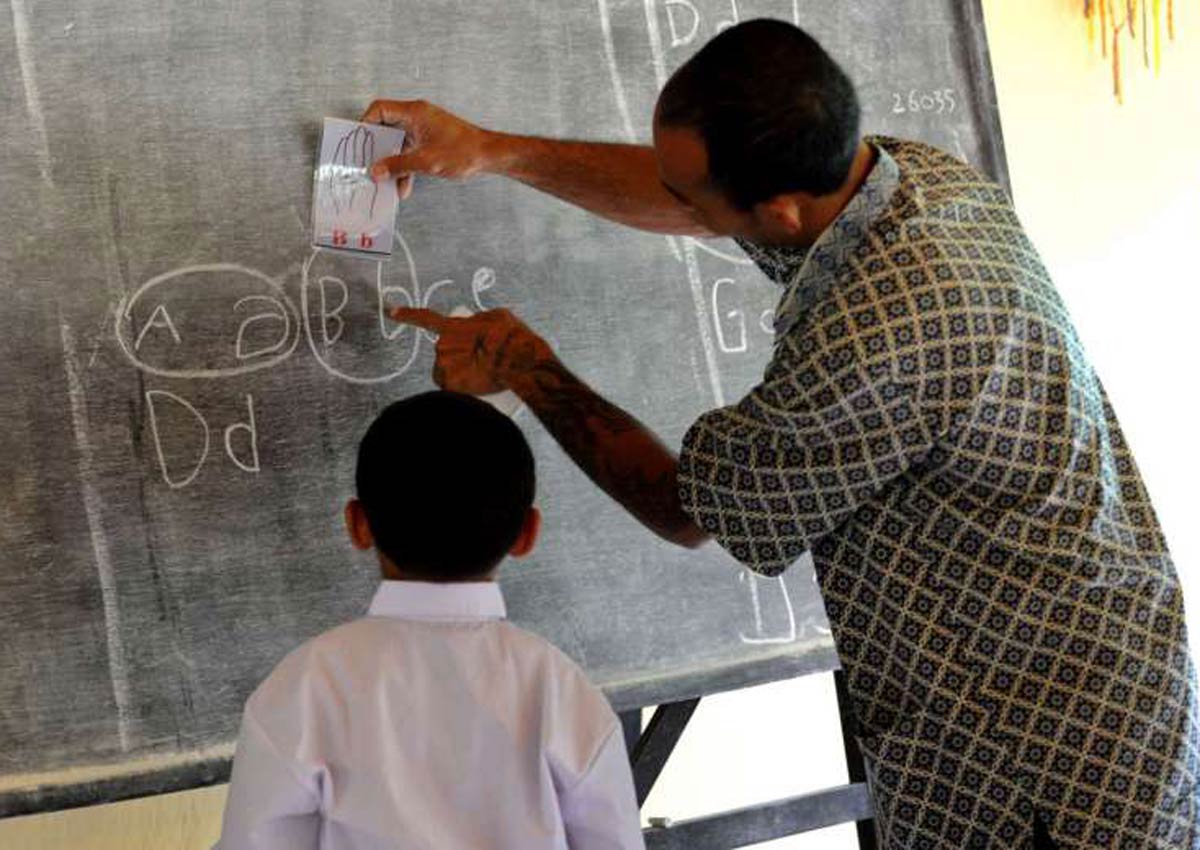

Attempts to ensure harmony in the village start at a young age, with a Bengkala elementary school teaching all children side by side.

The 77 students are all given lessons in the local sign language, and are introduced to elements of Indonesian and international signing.

Made Budiasih, whose seven-year-old son goes to the school, said she was worried for his future when they discovered he was deaf at birth, but said the inclusive educational centre had made all the difference.

“I was despairing, but then I found out about this school,” she said.

Still, it is not always easy teaching deaf students as they often become frustrated and act out, according to teacher I Made Wisnu, who has been working at the school for a decade.

There are no junior high schools equipped to teach deaf students, so most have to drop out of the system once they’ve graduated from elementary classes.

Despite the challenges, village chief Arpana is determined to safeguard the unique culture of the hamlet’s deaf community, saying he would be a “sinner” if he did not.

The clearest expression of the village’s warm embrace of its hard of hearing population is the unique project “dance of the deaf”, which has started to draw a trickle of foreign visitors to the out-of-the-way village, giving residents hope for a brighter future.

Tambourine player I Wayan Getar, speaking in sign language through an interpreter, told AFP: “Tourists from China and Europe are coming to watch us, and they really enjoy it.”