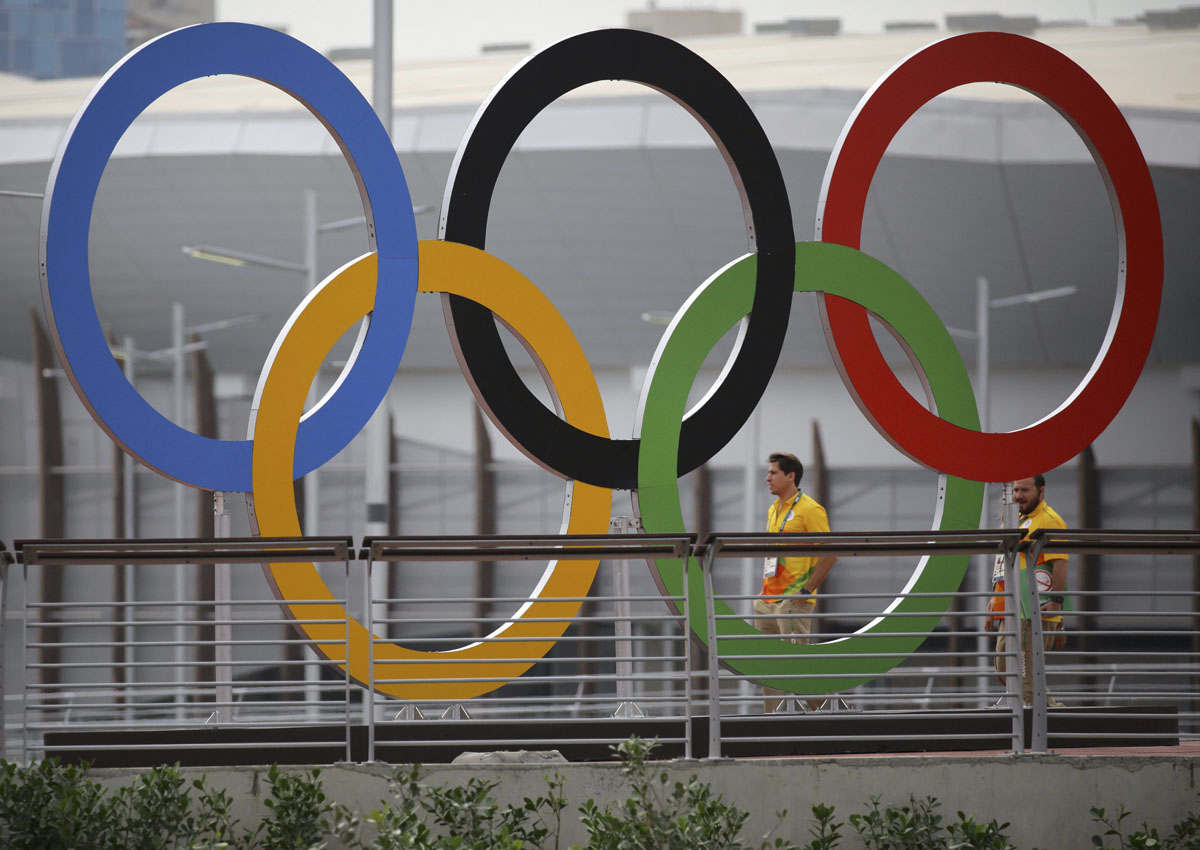

On lazy Sundays in September when my friends ask me about Rio, I might start with Jennifer Abel and Pamela Ware.

Early 20s. Canadians. Classy.

They lost diving bronze in the 3m synchronised springboard by .87 of a point and Abel cried and Ware was distraught and this was sport at the Olympics: Just another heartbreak in public.

Except they then composed themselves, marched to the mixed zone and talked.

To their press, to The Straits Times, to whoever asked, about mistakes they made and chances lost.

Ernest Hemingway should have been there: He’s the one who described guts as “grace under pressure”.

Or maybe I’ll tell my pals about the Russian, Yulia Efimova.

People called her a cheat, she got booed at the pool, she wept at the mixed zone. Then she turned up at the press conference only to receive disdain from an American rival and a relentless interrogation from the media.

She had to know that questions on doping and bans were inevitable and yet she came.

I’m a journalist, so obviously I like athletes who face questions and talk.

I also understand that athletes are human and different and are allowed to be furious, dejected and stomp off and kick a chair out of sight.

Sometimes you don’t want to talk; sometimes it’s just one of those awful days.

Though when Roger Federer has them, he still shows up. To talk. To print, TV, radio. In a ridiculous amount of languages.

There’s no doubt that swimmer Quah Zheng Wen, whose silent walk past the media a few days ago in Rio has become an issue, was having a tough day.

I respect that. I’ve also met Quah, 19, a few times and found him to be feisty, tough, ambitious, hard-working, likeable and smart. He clearly knows how to talk. And so I wish he had spoken.

Talking isn’t a favour, it’s simple professionalism, it’s part of their job and ours.

Yu Mengyu lost, covered her face, composed herself and then talked.

Novak Djokovic lost, cried like a man and then talked like one.

On the ATP Tour, tennis players get fined if they don’t talk after every match and they play close to a hundred every year.

Athletes don’t want the media to speculate on how they feel and guess what they’re going through.

Fair enough.

Our interpretation can be flawed because we don’t always know the details: That they slept badly, their goggles filled with water, their fever spiked and the fire alarm went off at 2am.

Want to fix that?

Talk.

Talk like the Indian shooter, who was deeply upset and terse at times but told his media that his sight broke before his event.

It wasn’t an excuse but just information which gave his day some perspective.

Athletes have told me that we, the media and the public, don’t know *&^ per cent about their sport, don’t appreciate its nuances and its intricacies, don’t comprehend what it’s like for dreams to die, what a crowd at an Olympics can do to your nerves and how hard they train.

They’re right, sometimes we don’t know.

How to fix that?

Talk.

Talk like Teo Shun Xie who told my colleague Jon that she felt fine before her 10m air pistol event, her sighting was good, and then they called “start” and she “suddenly didn’t feel good” and briefly forgot what she had practised.

This was insight, this was honest, this was how we comprehend pressure.

Athletes sometimes grouse about the inadequate attention they get: “You guys don’t care about our sport.”

They’re not always wrong either.

In Singapore, the media and the public are devoted to football which means less time on TV and inches in newspapers for everyone else.

In England, hockey players are ignored and in India, judokas must sulk.

Very few people care, watch, write on them.

How to (partially) fix this?

Talk.

At the risk of repeating a tale, one of my favourite interviewees was a world chess champion who brought his laptop along and spent an hour explaining his art to me.

And so, especially when major events occur, and TVs switch on, athletes should draw attention to their sport and their struggle by talking.

Even for a minute.

People may not know how divers clasp their hands when they enter the water. They may not understand why swimmers speak of “holding the water”.

If the athlete won’t tell us, we’ll never know.

Quah was hurting that day, no question, but how deeply we didn’t know.

Silence is not necessarily eloquent.

Debate on this subject will continue, but picking on a young swimmer or flagellating the journalist who first commented on him is pointless.

Bullying is never tasteful.

It’s more fun talking about Michael Phelps, who has won 21 golds but is still a half-dressed swimming preacher who uses the press conference as a pulpit.

By the time he finished his 200m butterfly the other day and then won another gold in a relay, it was 1.15am.

He’s 31, he has a tough schedule in Rio, he was exhausted and yet he still came.

To talk.

This article was first published on August 12, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.

6.jpg)