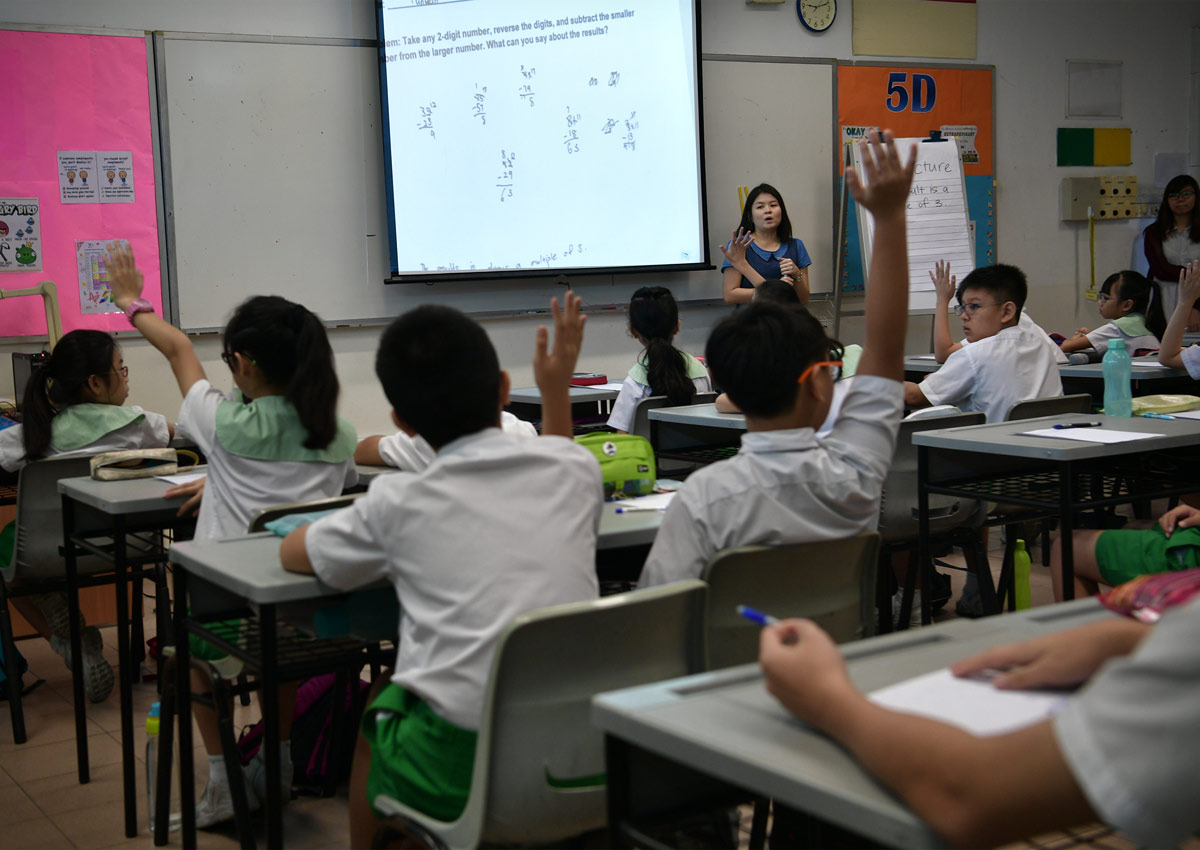

In a class last month, Primary 5 pupils at Woodgrove Primary School mulled over a mathematical puzzle unlike any standard problem sum.

The puzzle read: “Take any two-digit number, reverse the digits and subtract the smaller number from the larger number – what can you say about the results?”

“Try as many numbers as you like on a piece of paper,” said their mathematics teacher, Ms Lin Caili, 34, as she prompted pupils to test their hypotheses and explain their guesses.

“The answer is always a multiple of three,” one boy concluded.

“Maybe it’s a multiple of nine,” said another.

Ms Tan Hong Kai, 34, the school’s level head of mathematics, said the class was doing an investigative task on number patterns.

These open-ended activities, which she said are not usually tested in examinations, have been woven into lessons to equip pupils with higher-order thinking skills.

Such efforts by schools to encourage active learning have borne fruit, with Singapore students topping a global benchmarking test that measures how well they apply knowledge to solving real-world problems.

Read Also: Tuition industry worth over $1b a year

Earlier this month, 15-year-olds in Singapore were ranked No. 1 in maths, science and reading in the 2015 Programme for International Student Assessment (Pisa) test, dubbed the “World Cup for education”.

Last month, Singapore children in Primary 4 and Secondary 2 also topped another global mathematics and science test – Trends in International Mathematics and Science Study (Timss).

These results have placed Singapore on the world map and sparked discussion in media worldwide about the merits and flaws of the Republic’s education system.

Dr Kho Tek Hong, a former curriculum specialist who led a team in the 1980s to raise maths standards, said these results reflect the performance of Singapore as a country, not individual abilities, an indication that students from different academic streams were represented.

Science was the major domain tested in Pisa 2015, and the results showed teens here were strong in scientific enquiry skills and could use evidence to support claims.

An Education Ministry (MOE) spokesman attributed Singapore’s success in global studies to a teaching and learning culture which has built a “strong foundation in reading, numeracy and scientific literacy for all students”.

It also develops their thinking and communication skills, exposes them to application of knowledge in real-life contexts across subjects and gives them “positive attitudes towards learning”, he said.

Education experts point to Singapore’s ability to refresh its school curriculum and level up its teachers as key factors behind students consistently topping global rankings since the 1990s.

National Institute of Education (NIE) don Jason Tan, 53, noted that Singapore has managed to attain a high average achievement level compared with other countries in the region.

“This is helped by a rather centralised administration which can push reforms quickly from headquarters down to schools,” he said.

“Another plus point is the continuity in government, so there has not been much policy reversal.”

He also pointed to schools here having the resources to develop teachers, and physical infrastructure such as labs for learning.

CURRICULUM SHIFTS

Dr Kho, 70, said that Singapore’s journey to where it is today started with an overhaul of education in the 1980s to raise standards.

“The New Education system, as it was called, changed everything from school curriculum to teaching methods,” he said.

For instance, the former Curriculum Development Institute of Singapore was set up in 1980 to develop good-quality teaching and learning materials.

In those years, Singapore also looked to education systems in countries such as Israel and Japan, and studied how it could learn from various psychological theories.

“That was the start of slowly moving away from traditional rote learning and passive memorising over the next 30 years,” said Dr Kho.

“When students explore and are more active in learning, they make sense of concepts better.”

Since about a decade ago, the MOE has also made an effort to cut content across subjects, to make room for students to learn higher-order thinking skills such as logical reasoning and problem-solving.

This was done to free up time in schools for teachers to be more flexible and help students learn creativity instead of just content.

Dr Yeap Ban Har, 48, principal of Marshall Cavendish Institute, which conducts professional development courses for teachers, said there is a “clear direction” across the system today to train students to develop deeper inquiry skills.

For instance, since the 1997 vision of “Thinking Schools, Learning Nation”, curricula and assessment have focused more on critical thinking skills and creativity, he said.

Read Also: Pisa and the creativity puzzle

Increasingly, national examinations are also testing more application-based questions in novel scenarios, said Dr Yeap, who spent 10 years at NIE’s mathematics and mathematics education academic group from 1999 to 2010.

Twelve-year-old Gary Gan, who finished Primary 6 this year, said “higher-level” mathematics questions can be frustrating but he enjoys them as they help him think more.

“Maths helps me learn to solve problems and I think this will help me in the future to solve more challenging problems,” he said.

Dr Ridzuan Abd Rahim, an MOE lead curriculum specialist in mathematics, said: “It is no longer enough that we just know something.

More importantly, we need to know how to learn something new and how to apply what we know to new situations and problems.”

Today’s society and economy require workers to take ownership, be adaptive, and adapt ambiguity and complexity as the norm, said CHIJ Katong Convent principal Patricia Chan.

That is why curriculum has to evolve from one totally focused on content, to equip students with such skills for the future, she said.

In response to these rapidly changing needs, science and humanities subjects have been refreshed to equip students with skills for the future such as teamwork and the ability to analyse, be creative, make links and solve problems.

Lessons are now more grounded in real-life contexts, requiring students to apply textbook theories outside the classroom.

For instance, Ms Chan said students would learn about the total surface area of a cylindrical container in relation to understanding why and how manufacturers minimise material cost when canning drinks.

“In the humanities, the move towards the inquiry approach positions itself away from typical rote learning, where one can score by just memorising,” she added.

Students now need to make links between concepts and draw their own conclusions, using investigative work and examples from current affairs in the process, she said.

Pupils are also encouraged to speak up more so they are able to express themselves confidently.

A national curriculum called Stellar, short for Strategies for English Language Learning and Reading, was piloted in some schools in 2006 with the aim of developing pupils’ ability to use the English language confidently in real-world scenarios.

Stellar, which does not rely on textbooks and instead uses storytelling, role-playing and texts such as news articles in lessons, was extended to all primary schools in 2009.

Schools also pay more attention to developing students beyond book smarts through applied learning in topics such as robotics, food science or transport.

These programmes, said Dr Ridzuan, give students a chance to experiment and take on hands-on activities that apply to the real world.

TEACHER TRAINING

The other plank of Singapore’s global success lies in teacher training.

Experts said NIE and its predecessors have played a key role in training educators centrally over the years.

NIE director Tan Oon Seng said its partnership with schools and MOE ensures that teacher education is in line with “larger teacher policies, Singapore’s education priorities and aspirations, and the ground challenges in schools”.

For instance, to teach students higher-order thinking, teachers themselves must be equipped to “ask questions, to guide and facilitate students to think… beyond information or knowledge imparting”, said former NIE director Lee Sing Kong.

Professor Low Ee Ling, head of NIE’s strategic planning and academic quality, said having a central body that trains teachers is what makes Singapore “a very unique system”.

This model began with the setting up of the Teacher Training College in 1950.

Before that, many teachers had little or no prior formal teacher training, leading to uneven quality of teaching standards across schools, she said.

Today, around 85 per cent of teachers are graduates, and at the primary school level, seven in 10 teachers have a degree.

Read Also: Parents ponder value of Pisa test rankings

NIE trainee teachers, called pre-service teachers, also go on practice stints in schools to help them link theory to practice.

The MOE has also been improving pay and promotion prospects for teachers.

For example, in October last year, up to 30,000 teachers received a 4 per cent to 9 per cent increase in their monthly pay.

Mentorship schemes introduced since 2006 have also helped new teachers hone their craft on the job.

Each beginning teacher is matched to a mentor in school who provides guidance in areas such as classroom management, basic counselling skills and assessment skills.

St Stephen’s School teacher Gion Pee is grateful that the system emphasises beginning teachers’ professional growth.

The 33-year-old, who joined teaching in July 2012, had a one-year induction where he learnt teaching and management skills from senior teachers.

Since January this year, he has received tips on teaching English during weekly meetings with his mentor, Madam Azizah A. Rasak.

The sessions helped him to reflect on how to differentiate his teaching style to suit his pupils’ learning needs, he said.

Dr Charles Chew, principal master teacher in physics at the Academy of Singapore Teachers, said: “Teaching is a highly complex craft that needs to be constantly sharpened and honed to meet the needs of students… A good teacher is one who does not teach the subject but teaches students the subject.”

This article was first published on December 25, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.@sph.com.sg>