Along Telok Ayer Street, shophouses have lined narrow lanes for more than a century.

The terraced structures, which once housed provision shops on the ground level and cramped quarters above, have been converted into bars and bistros which serve workers from nearby offices.

With the bustle of activities that permeates the street daily, it is almost easy to miss the cream-coloured building. Make no mistake though, the Al-Abrar Mosque has an unwavering presence.

Built in 1827, it has stood the test of time, even as its neighbours have changed. The mosque began as a small thatched hut, and was nicknamed Kuchu Palli – “hut mosque” – in Tamil. “It was where the Chulia or South Indian immigrants gathered to pray,” said Mr Mohamed Sulaiman Mohamed Arif, the mosque’s secretary.

The Chulias were among Singapore’s earliest immigrants. They worked as traders and money changers in Chinatown, hence the mosque’s other nickname: Chulia Mosque.

The hut was upgraded into a brick mosque over five years from 1850 and underwent a series of major renovations more than a century later. Today, it has expanded to take the space of three shophouses.

Flanked by two large minarets, the main entrance leads past a five-foot-way and up some steps into the main prayer hall.

Former postman Hasan Kutus recalls raised platforms at the entrance where worshippers would gather in their free time.

“This was where the thinnai (raised platforms) used to be,” said the 69-year-old retiree, pointing to the steps. “Food was served, people would sit and talk. After the HDB blocks were built and the community scattered, the place became more quiet at night.”

As a young man, Mr Hasan frequented the mosque daily during his time working for Singapore Postal Services at the nearby Fullerton Building from 1969. He remembers performing his ablution, or ritual cleansing, at a large pond next to the prayer hall. “During the 70s, there was no room to cleanse and wash, so people would take their wudhu (ablutions) at the pond before praying,” he said.

Worshippers prayed on straw mats laid on the cement floor. While the hall has since been fitted with carpet flooring, Mr Hasan recounts the joy of the simple days. “It is a simple mosque but when we came here, we found happiness,” he said.

Mr Abdul Latiff Syed Mohamed, 67, who has worshipped there since the 1970s, said praying at the mosque is special to him too. “When you pray here, the feeling is different from other, newer mosques,” he said. “The energy level is different.”

Mr Latiff, director of a trading firm, visited the mosque every night during his teens.

Added the mosque secretary, Mr Arif: “Other than a spiritual refuge, the mosque served as a social venue where people met up.”

Together with the Nagore Dargah, a former Indian Muslim shrine down the street, the Al-Abrar Mosque became an important religious monument for the Chulias. Both buildings were gazetted as national monuments by the National Heritage Board in 1974. Within the historic vicinity are three other national monuments: Telok Ayer Chinese Methodist Church, Thian Hock Keng temple and the former Keng Teck Whay Building.

The mosque went through a series of major renovations between 1986 and 1989 during which an additional storey was built and the courtyard at the entrance gate covered to create more space.

It also acquired the adjacent shophouse and converted it into a prayer hall for women. After the upgrading works, the mosque could cater to 800 worshippers, up from about 60 in its original space.

Today, the mosque stands out from the other shophouses along Telok Ayer Street with its Indo-Islamic architectural style. Six minarets line the entrance, two of which are crowned with the Islamic symbol of a crescent moon and star.

Inside is an eclectic mix of East and West. The mosque weaves its history into the architecture with coloured glass panels fitted in the fanlights above large French louvred windows. Wooden parapets line the sides of the mosque and its interior is held up by Doric columns.

Then, there are the familiar features of a prayer hall that distinguish it as an Islamic place of worship – such as the mihrab, a niche that points towards Mecca in the direction that Muslims pray.

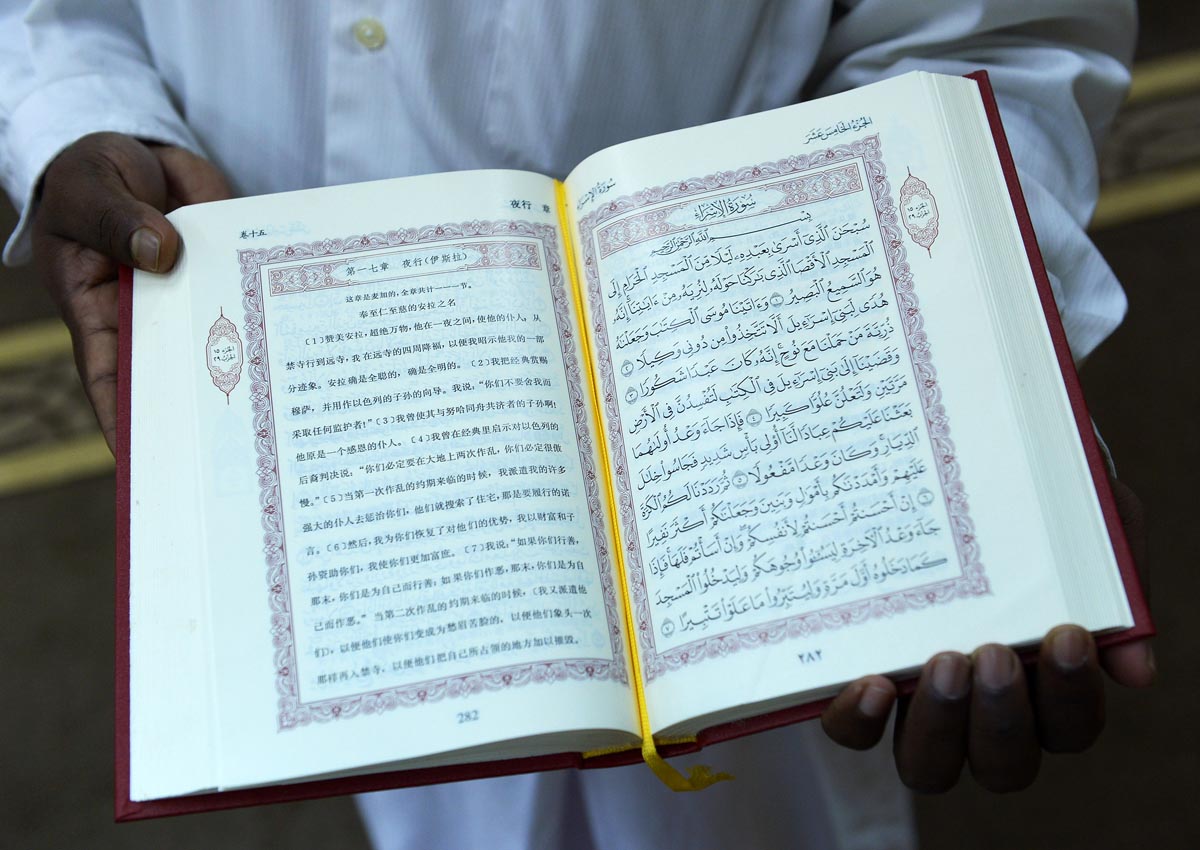

Sunlight pours from a blue glass panel inscribed with a verse from the Quran. “During sunrise and sunset, you can see the shadow of the verses on the carpet,” said the mosque’s Mr Arif.

Less familiar is the newly mounted television on the wall in front. “A lot of Malay office workers come here during lunchtime. The TV is to help translate the Friday sermons, which are in Tamil,” Mr Arif said.

While Al-Abrar Mosque continues to serve a predominantly Indian Muslim group, it sees more Malays during weekday afternoons, many of whom are office workers from the nearby business district.

Photo: The Straits Times

“The mosque is open to all,” said Mr Arif – even tourists and other visitors who are not Muslims.

“Old people say that when they have problems and they feel down, they come here and they will find peace,” he added.

“That is why we hope that we can preserve the mosque until the end of time.”

rahimahr@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on September 29, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.