I remember my own childhood vividly. The weeks were filled with school, piano classes, private tuition for quite a few subjects and swimming lessons on Sunday afternoons.

But I also remember the moments in between – learning to cycle with my father on Saturdays, having dinner with my family every night, camping on the beach at Pasir Ris Park and the holidays abroad.

I don’t remember much of classroom lessons in primary school – only running down a grassy slope with friends, playing hide-and-seek around the school stage and, of course, recess time.

My schedule was packed, spare time was precious and rest time cherished.

At times, I was so tired I dozed off during tuition sessions, and I was secretly happy if my tutors had to cancel.

Yet, there was still disappointment when grades did not seem to match the work put in, and fear of facing even more disappointed parents and having to explain the results.

I pulled through and knew my parents acted in my best interests.

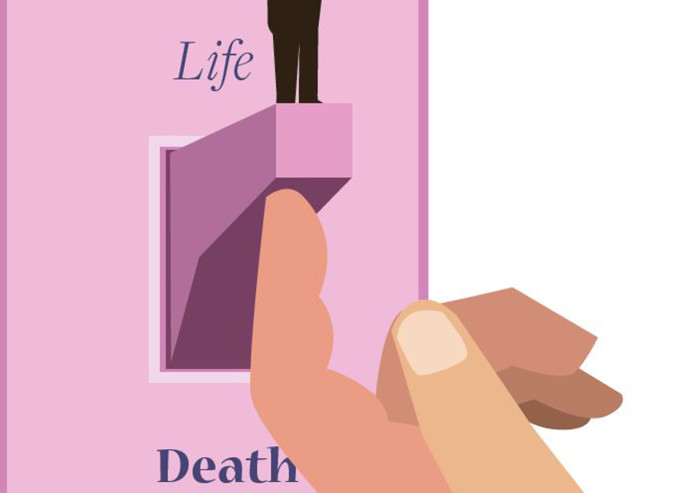

Stress on young children here is nothing new, but it recently came under the spotlight after a Primary 5 pupil killed himself in May.

According to a coroner’s inquiry in October, the boy had failed his examinations in Higher Chinese and mathematics and was due to show his parents the grades that day.

Read also: Death of boy, 11, who fell 17 floors after failing his exams for the first time ruled a suicide

This made many parents sit up, especially after latest figures revealed that there were 27 suicides last year among 10- to 19-year-olds – a 15-year high.

This is double the 2014 figure, despite a drop in the overall number of suicides.

This trend is not unique to Singapore – in Britain and Hong Kong, suicides among the young are on the rise as well, shocking the authorities and prompting preventive measures such as engaging parents and improving counselling in schools.

Schools here are also paying more attention to students’ mental wellness. Efforts range from starting peer helper initiatives to encourage students to speak up about their difficulties, to organising talks on mental health and setting up rest corners. And yet, the stress seems only to climb.

Mr Brian Poh, clinical psychologist at the Institute of Mental Health’s department of child and adolescent psychiatry, says: “Children do face pressures in different areas of their lives.”

These could range from academic-based stress to relationship issues such as friendship and bullying problems.

They face expectations from parents or teachers, and sometimes these pressures could be self-perceived, he added.

On top of that, there are hormonal changes that could play havoc with adolescent emotions.

Most children need to be pushed to work hard and some stress is needed but they should not be weighed down to the point that they feel crushed.

Suicide numbers are only the tip of the iceberg; many others develop psychological problems such as depression, anxiety and extreme mood swings.

Some even resort to self-harm in their teenage years.

Part of the problem is the faster pace of life today, said counsellors, and in smaller families, children face higher expectations to achieve.

Growing up in an increasingly digital era also means some young people retreat into the virtual world instead of spending, quality face-to-face time with family or friends.

Read also: Youth suicides here hit 15-year high last year

A FINE BALANCE

The education system’s longstanding focus on exam grades and book smarts, resulting in parents’ obsession with academic performance, is changing, albeit slowly.

In recent years, the Ministry of Education has taken steps to relieve some pressure, from not naming top scorers of national examinations to removing school ranking.

It has also invested more in programmes to nurture students’ strengths in other areas, such as sports or music.

And the Primary School Leaving Examination (PSLE) T-score – a key source of excessive stress for young ones – will be done away with in 2021, and pupils will no longer be graded relative to their peers.

But many parents and pupils still feel the need to keep up in the education race as long as there are high-stake exams and children are measured by grades.

Some said the ministry’s efforts to focus more on children’s holistic development come too late, after years of “conditioning” that have resulted in a mammoth system so ingrained in traditional notions of success.

There is also a sense that school curricula and exam questions are getting more difficult. So parents want their children to attend any optional supplementary classes offered by schools so as not to miss out on anything extra that is taught.

Fears of losing out have also helped create a booming shadow education industry in private tutoring, where paying for extra lessons outside school has become the norm rather than the exception.

It seems society as a whole – and that includes parents, students, policymakers and educators – has to re-examine its values and definitions of success.

While it is never easy for parents to go against societal expectations and to resist the urge to compare their children’s grades to others or strive for them to get into brand-name schools, perhaps more will do so over time.

There are parents now who say they refuse to bow to the pressures of signing their children up for tuition or enrichment lessons, or buying extra school exam papers, unless they really need it.

One parent, Madam Shirley Woon, 50, said she makes it a point to pack her children off to bed by about 9.30pm every night even if they are not done with their homework, and even if that means they risk the ire of teachers.

“Homework is important, but health is more important,” said the counsellor. “The mind needs to rest, the body needs to recover. It’s a matter of time before the body collapses if it is overworked.”

Research has shown that play is essential to the cognitive, physical and socio-emotional development of children especially in their early years.

Yet, in reality, this is not a priority for most families. Parents admit that the number of hours children devote to academic work is far more than any spent on play and rest.

And with many parents also busy with their work lives, when they come home in the evenings, conversations with their children often revolve around what is deemed more important and needful – if homework has been done or if they have revised schoolwork for tests.

Said Madam Joyce Ong, who has a Secondary 1 daughter: “I’ve heard of other kids who are very fatigued. They come home from school, rush through dinner, have tuition at night and go for tuition on weekends. I’m hoping not to put her through this,” said the 42-year-old property agent whose daughter currently does not have any tuition.

Read also: Survey to be formed to study suicides among young people

PARENTS’ APPROVAL

To children, a parent’s show of approval, disappointment or anger are signs of affirmation and acceptance, or otherwise, said counsellors.

Children need to know their self-worth is not defined by academic marks on their report cards.

They need to know their parents will support them even when they fail. Only then are they more likely to open up to their parents and share their fears and struggles.

Psychologist Daniel Koh from Insights Mind Centre said: “Before a child can confidently speak to his parents and feel safe and secure as well as supported, parents need to show that the child will be accepted and loved unconditionally.”

Communication with children has to go beyond their studies and results, he added. Instead, the focus must be on helping them be resilient when things don’t go their way.

Resilience is not just about dealing with school stress, but having the strength to face all challenges. Schools here are opening up to discussing mental health, especially among adolescents, and that is a first step to helping them build resilience.

These are not easy lessons to learn in the immense task of parenting – it takes significant courage and resolve to go against the grain and do what is better for your child.

Next month, I will become a first-time mother. People have asked if I have looked at securing a place in brand-name pre-schools with waiting lists, or if my husband has joined his alma mater’s alumni association so our son will have a higher chance of entering his school at Primary 1.

The years of schooling are far away, and those thoughts have not yet crossed my mind.

I want the first conversations at home about our son to be about the values we want to instil in him, not which schools we want him to go to. I hope to be an involved parent, yet know when to take a step back and let go.

I want him to learn resilience in times of stress and in the face of failure. I want him to understand that challenges and mistakes are part and parcel of life and that we learn most from them.

But I also know raising a child will not be easy, as many parents I have spoken to in the course of work have shared.

I anticipate the uphill struggle in the years ahead – there is the fear of being too caught up in the rat race of education, but on the other hand, there is also the fear that he will “lose out” if he does not join the race.

My hope is that when the time comes, we will make the right choices – not just for our child to get ahead and be a good student, but to grow to be a better, happier, and more well-adjusted person.

Read also: What drives teens over the edge?

Helplines

Samaritans of Singapore (24-hour hotline): 1800-221-4444

Tinkle Friend: 1800-274-4788

Singapore Association for Mental Health: 1800-283-7019

Care Corner Counselling Centre (in Mandarin): 1800-353-5800

Mental Health Helpline: 6389-2222

This article was first published on Nov 24, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.