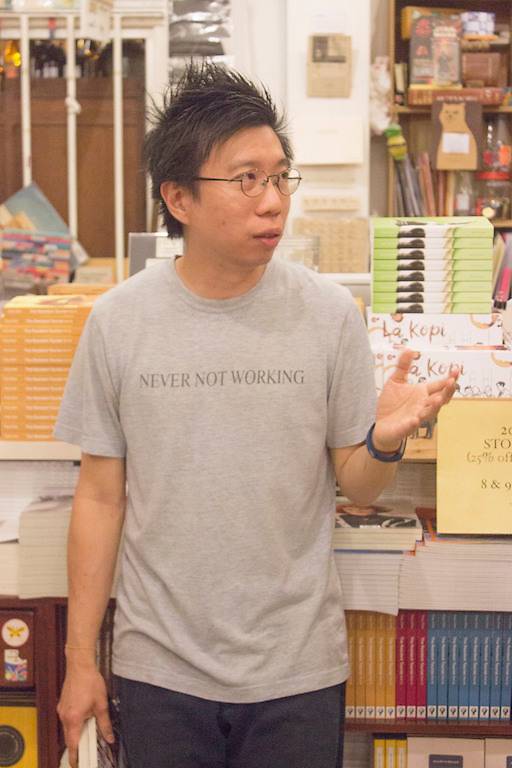

SINGAPORE: Kenny Leck looks nothing like a conventional businessman but in his field he is considered a formidable force. In an era where many major bookstores have closed down, his independent bookstore BooksActually has survived and is going strong after 13 years.

When I arrive there, he is behind a stack of books next to the cashier. He wears a nondescript T-shirt and glasses. The only thing that is easily visible from afar is his spiky black hair.

It’s a weekday and only a handful of people are browsing the rows of books that stretch from floor to ceiling at BooksActually at Yong Siak Street in Tiong Bahru.

We move into a backroom to talk. The 40-year-old answers questions with aplomb, but it feels as if I’m speaking with someone who is more a booklover than a businessman.

However, to survive in this business, you “necessarily have to be both”, he concedes.

To listen to the full interview, click here.

The business turned a modest profit of S$80,000 last year. For a single bookstore, “that’s actually quite ok”, he says. To a great extent, the figure is modest because he has been pumping more money into boosting the bookstore’s publishing arm, Math Paper Press, through which he often publishes local work that may not always make money, but that he considers important to “put out there”.

“When someone sends you a manuscript, whether it’s fiction, non-fiction, or a children’s book, they are trying to tell a story. Especially if it is a Singaporean who has submitted the manuscript to you, they’re trying to tell you a particular narrative of their own. And that narrative is as important as us winning an Olympic gold medal. Because that’s part of who we are, that’s part of our history.”

Investing in publishing has slowed down his progress towards buying a permanent retail property for the bookstore.

While he and his co-founder have been making the business work entirely on their own dime so far, they recently started a fundraising effort to rope in investors to help them do this.

“It’s more sustainable than paying rent and we hope we can do this through this crowdfunding effort.”

Over the last 13 years, they have moved three times, each time due to an increase in rent but for the last seven years, they’ve managed to establish some stability in Tiong Bahru.

The current rent is about S$10,000 a month but he’s not complaining.

“If you’re a good business owner, regardless of what the rent is, low or high, (if) you know that the location works for you and the numbers are proving right, you’ll just stay. So for now, it’s fine. But in the future, we don’t know what’s going to happen and who wants to be a sucker to any landlord who’s going to increase your rent by 50 to a 100 per cent?”

While he bemoans high rents, he doesn’t believe, as some businessmen do, that the authorities should intervene to control them.

“That’s just how the free market economy works. If you expect the landlords to reduce rent or if you ask the Government to intervene to reduce retail rents, you’re just being lazy and asking to be spoon-fed. We have to remember that it’s not free money. Rental subsidies will have to come from taxpayers.

“Business people should just accept this is the way it is, crunch your numbers well and do more to make your business successful. That’s what we have been trying to do. But if the price is too high, then you have to move. That’s just how the economy is. But we also want to explore other options such as having our own property.”

I remark that his public fundraising effort for this could be construed as “asking to be spoon-fed”.

He disagrees.

“We are aware that nobody owes us a living. It’s your private money. If you decide to help or invest, then do it. If you decide not to help, it’s fine too,” he says decisively.

We talk more about the numbers and his strategy to convince people to help later but to understand Mr Leck’s motivations it’s necessary to take a step back.

Kenny Leck, owner of BooksActually has also started a publishing arm, Math Paper Press.

WOULD HE AMOUNT TO NOTHING?

He came from a low-income family. His father was a taxi-driver and his mother a housewife. They both recognised the importance of reading.

“My mum was a typical parent who read a lot of self-help books about parenting. While she encouraged me to spend a lot of time in the library, she was also never stingy when it came to buying books for me.”

He attributes his desire to own books instead of simply borrowing them from the library, to a “covetous” instinct that he believes many book lovers possess.

“My mother would never say no. She would crunch her own numbers and figure out how she can transfer money from her household expenses to buy me books. I remember in school when there was an opportunity to buy several sets of encyclopedias, she bought them for me on a three-year instalment plan.”

He dropped out of an accountancy and taxation diploma course in a local polytechnic just two semesters before graduation and went to work at Borders before co-founding BooksActually in 2005.

He picked the polytechnic course for a very specific reason.

“My dad fell very ill when I was 17 so the family needed me to come up with a solid income after National Service (NS). I chose all the business-related courses, and I ended up with Accounting and Taxation. It was a very clear route. If you’re there, after NS you can just go on to do your accounting papers, and eventually you can become a chartered accountant which pays really well.”

But things changed. His father became better and landed a well-paying job at a church. This helped seal his decision to turn his back on school to pursue his dreams.

His polytechnic course manager at the time actually told him he would amount to nothing. His memories of this are still very vivid.

“I remember this person, but I understand why she said it. It was the context of that time. I think many people didn’t believe that you could succeed without paper qualifications. I was actually doing well in school. I was probably one of the top 10 students and I enjoyed studying things like taxation. But I also knew it’s not something I wanted to do for the rest of my life.”

His parents seemed to understand his decision.

“I told my dad I wanted to quit, and broke down the number of years that would be saved if I were to quit immediately, and he told me to go ahead. That’s what my parents have given to me. Since I was a kid, they’ve always trusted me to make my own mistakes, and to own them to make decisions, whether good or bad.”

BOOKSTORES HAVE ONLY THEMSELVES TO BLAME

Working at major bookstores such as Borders and Tower Books taught him what not to do.

He has said in previous interviews that the mistake many of these stores made was to sell non-book merchandise such as stationery, movie posters, gadgets and even snacks.

He admits now that he was guilty of this too, albeit to a much more limited extent today.

“Booksellers are guilty. All of us are guilty. There were phases of this bookstore when we brought in non-book products because they brought in the money. As we went on, we realised that we are a bookstore, so why are we selling all these things? If we’re a bookstore, let’s work harder at selling books.”

His focus is on displaying and marketing the books well and to that end, he sets up pop-up stores around the island. He believes that consumers should not be blamed for losing interest in reading or in physical books.

“The bookstores that haven’t made it have only themselves to blame. I’m in the business so I know. Sometimes, they receive stock and they don’t display it. They’ll leave it somewhere in a box. Three months later, they’ll tell you that the books don’t sell. So who is to blame? Is it the consumer, or is it the bookstore manager that managed the outlet? Or is it the top not managing the business well enough to ensure that when the books come in, they get processed and displayed?

“And not just displayed in terms of shoving it in, but making a nice visual display, and doing enough marketing and branding.”

“The bookstores that haven’t made it have only themselves to blame. Sometimes, they receive stock and they don’t display it. They’ll leave it somewhere in a box. Three months later, they’ll tell you that the books don’t sell,” says Kenny Leck of BooksActually. (Photo: Facebook / BooksActually)

FEAR AND ANXIETY

He set up his first bookstore in Telok Ayer Street with less than S$25,000.

“We borrowed $20,000 from my co-founder’s mom. We had maybe S$1,000 in our bank accounts. I borrowed S$700 from my dad. I remember because my dad had to take the loan from a fellow church member, and I had to pay it back within the month, so the number was very clear-cut.

“We picked up quite a bit of contractor skills. We actually made our display tables from discarded wood mounted on Ikea shelving units. We did quite a fair bit of painting ourselves. A lot of our marketing materials were made in-house. The do-it-yourself philosophy became more pronounced as the years went by. The current wooden wine crates that you see in the bookstore today were all mounted and put together by us. We sourced the wine crates, planned the layout, and then fitted it into the walls.”

When they first started out, there would be days when there would be no sales whatsoever.

He remembers the fear and anxiety he felt then.

“I think for any retailer, bookstore or otherwise, that’s the scariest thing that could ever happen. I remember that happening a few times in that first year. One day I fell ill, so I decided to take a break. The second day, I was actually feeling okay, but I was feeling so demoralised that I decided to stay at home another day. Then another. On the fourth morning, I woke up and I decided I shouldn’t do that, no matter if there are sales or not. I should just suck it up, open it up because you never know what’s going to happen.”

He calls that period a turning point.

“If I was serious about running the business and if there’s zero sales, it means that I’ve do something about it whether it is organising an event, doing more marketing, doing more branding, get people in and get the sales.”

He was to face even more challenges later though.

He sold a 3-room HDB flat that his mother left him when she died and with the S$200,000 he made from it, he set up a second bookstore at Club Street which failed.

“I miscalculated. The space there was huge and we had to buy stocks from scratch. We had to buy a lot to fill up that huge space that we had. And the money burned faster than you could ever think.”

They had to close it eventually, but thankfully have managed to continue sustaining at least one store till today.

WHY INVEST IN A BOOKSTORE?

I ask how his fundraising efforts to purchase a commercial retail property for the bookstore are going.

The BooksActually Shophouse Fund has only made S$20,000 to date. They’ll need much more for a downpayment.

“An ideal location in Jalan Besar where it’s got a good vibe and slightly, but not totally gentrified, in total, will set us back about S$5 million. For a not-so-ideal location, but a location that we still like, it’ll be about S$2 million.”

He is considering the Balestier area.

I ask him what his proposition to donors is. Why should people contribute to this fund?

“I guess it’s about possibilities. Over time, we have connected with a lot of people, formed relationships and we have discovered simple things. For example, just two months ago, a customer who used to visit us at our previous location came back from the UK after completing her studies and she told us that she’s so happy to see us still around, because now she can show her kid what the bookstore meant to her when she was still studying in Singapore.”

I remark that it all sounds merely sentimental. What’s the business rationale?

“There’s no business rationale. There’s only that very intangible part of it. Everybody’s always asking where are our roots? Where is our commonality in this country, right? If they like to ask that but they tell you that actually we have no roots in this country because everything is changing so fast and places are disappearing, they are obviously not looking hard enough or not investing in it.

“Maybe someone down the road that you might be married to, or your kid might end up being a writer, might end up being a musician, might end up being an artist who we end up supporting. When you invest in us, it comes back around to you.”

But it seems as if he hasn’t managed to convince many people with that argument.

He ascribes the dismal contributions to a lack of publicity for the fundraising efforts and intends to ramp them up progressively.

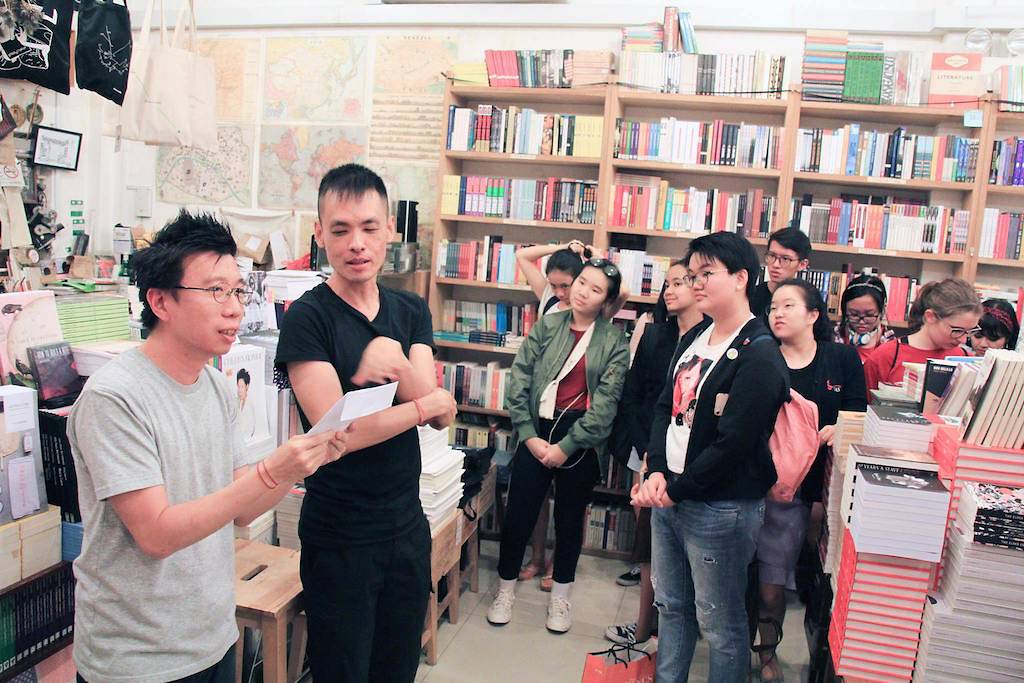

A book launch at BooksActually. (Photo: Facebook / BooksActually)

STANDING FOR SOMETHING

But he reveals that “quite a handful” of private investors have actually offered to contribute, but once they realised what he stood for, they retreated.

“Bookstores tend to have a certain amount of character, and the character here is derived heavily from me – the person running it. For example, I am against discrimination and injustice, so a few years ago when the National Library Board pulled some books from their shelves because they highlighted different types of families including same-sex parents, we took a stand. We went to Amazon and bought all the 300-odd copies of And Tango Makes Three left in stock and sold them at our bookstore.

“We stand up against anything that discriminates against another person but some of our potential investors with deep pockets are of a certain social standing, and they are not comfortable aligning themselves with such causes.”

He clearly would rather reject the money than relinquish his ideals.

For now, he concedes that his modest profits will not get them far in terms of acquiring property, but he is determined to soldier on.

His ultimate goal is to have one large bookstore modeled after The Strand Bookstore in New York City.

In other respects, he is happy to continue living humbly.

“I currently only draw an allowance that covers food and transport, and I rent an apartment near the bookstore which doubles up as our publishing office, and storage area for our book stocks, plus bookstore supplies.

“I don’t take any holidays. For the first nine years of the bookstore’s existence, I did not travel because that was an unnecessary expense. When I had the chance to go to Bangkok after being invited to be a speaker in 2015 for the Bangkok Literary Festival they paid for all my expenses.”

Considering that at this time, he can’t afford to expand or buy his own retail property, clearly the bookselling business, on the scale he does it, has its limitations.

I ask if wealth is even a goal of his.

“I want to achieve wealth but I want to achieve wealth that enables me or the bookstore to help those who need it most because I’ve experienced what it’s like to grow up in a low-income family. I’ve seen how my folks struggled to make ends meet and not deprive their two kids of basic material comforts.

“The lowest point was when my father fell ill, nearly died, and with the loss of the sole-breadwinner in the family, we were suddenly at a loss. I was 17 that year doing my ‘O’ levels. We were either very, very lucky or blessed or both. His major hospital bills were close to 80 per cent subsidised by the government based on our income level, and for the rest, our church stepped in. That kind of support meant that my mother could ease her way into a job.”

Experiencing this “lack of wealth” has put him on a path to be as self-sufficient as possible but it has also ingrained in him a deep belief that any wealth gained must be used to help another person in need.

In his business, he classifies budding writers as “those in need”.

Through the publishing arm, Math Paper Press, he goes out of his way to help them in spite of the fact that some of the work lacks quality.

“There’s definitely a quality deficit. Over the years, it has of course improved by leaps and bounds, especially in the last decade. But we’re always going to have a quality deficit because there’s not enough being pushed out. How are you going to reach higher standards when you only have three or four serious publishers, compared to a city like London where they have many more. They also have a longer history than us.

“But we already have some really good work too that gets ignored because sometimes local publishers don’t push it hard enough. We have to do a better job.”

In the meantime, he sees it as his responsibility to give all writers a “good debut”.

He contributes to society in other ways by sponsoring books for community reading programmes for children from low-income families. Recently, he also contributed several thousand dollars to helping pay rent for a shelter for transgender individuals.

Kenny Leck is regularly seen at book fairs and events, a necessary part of his bookstore’s outreach efforts. (Photo: Facebook / BooksActually)

STAYING RELEVANT

As we turn to talking business again, he concedes that in some quarters it’s believed that physical books will become passé no matter how well they are marketed.

“I think the covetous side of book lovers – the fact that we are tactile beings – will ensure there’ll be a market for books. But I also know that there are questions about how environmentally-friendly all this is.”

I point out that e-books have a carbon footprint too, but ask him to justify why he continues his business in spite of his concerns.

He thinks the trade-offs are worth it.

“With books, we push knowledge and insight. All of us have been impacted by one or a handful of books. I think that’s where the value is. You are consuming resources, but we are producing books for pushing conversations, for keeping narratives, for pushing the envelope. Using paper to produce a book is much more valuable than using the same resources to produce a memo-pad.”

Some suggest that in a country with very good public libraries, buying books may in fact be wasteful too.

But he insists that book lovers’ covetous instincts that he alluded to earlier can make bookselling a viable business long into the future.

In fact, he welcomes competition.

“If we want to become a nation of readers, you need to have more bookstores. People today would rather open a cupcake shop than a bookshop, but they don’t know how to crunch numbers. They’ll always tell you that there’s a great number of people who will eat cupcakes, but soon many of these businesses will fold. I believe if they crunch the numbers right and did the right marketing and publicity, they’ll see bookselling can be viable.”

Competition, he believes, will also keep him and his team from becoming complacent.

His advice to budding business owners is simple.

“Don’t go in with the mindset of trying it for just two to three years and falling back on something else you’re more familiar with. If you go in with that mindset, you’re setting yourself up for an easy failure. If you’re faced with a life-and-death situation, you will think of more ways to stay alive, right? In business it’s the same thing, if you are presented with one problem, there can be multiple solutions. But if you go in with that mindset, you won’t even be able to see these solutions. You’ll just give up.”

While running a sustainable business is clearly important to him, when asked what impact he’d like to ultimately make in the industry, his answer has very little to do with monetary concerns.

“I always say the best way to die is to be just sitting in a chair reading a book, and to suddenly just expire. But throughout my life, I remember the individuals who’ve left a huge mark on me, whether teachers, parents or friends. I think that’s the most valuable thing. In your toughest times, you look back and know that those individuals have propped you up, put you on their shoulders so you can walk better. Hopefully, I can be that support for others in my personal and business life.”