Most Singapore seagrasses have not been sexually propagated for at least three to four years, and the scientists concerned are trying to figure out what is wrong.

The lack of sexual reproduction – the creation of new plants through flowers and seeds – may lead to a decline in the genetic diversity of seagrass populations, making them more susceptible to mass mortality.

This will harm the environment in many ways because seagrass meadows store up to 30 times more efficiently than rainforests and are key breeding grounds for marine animals such as dugongs in Singapore waters.

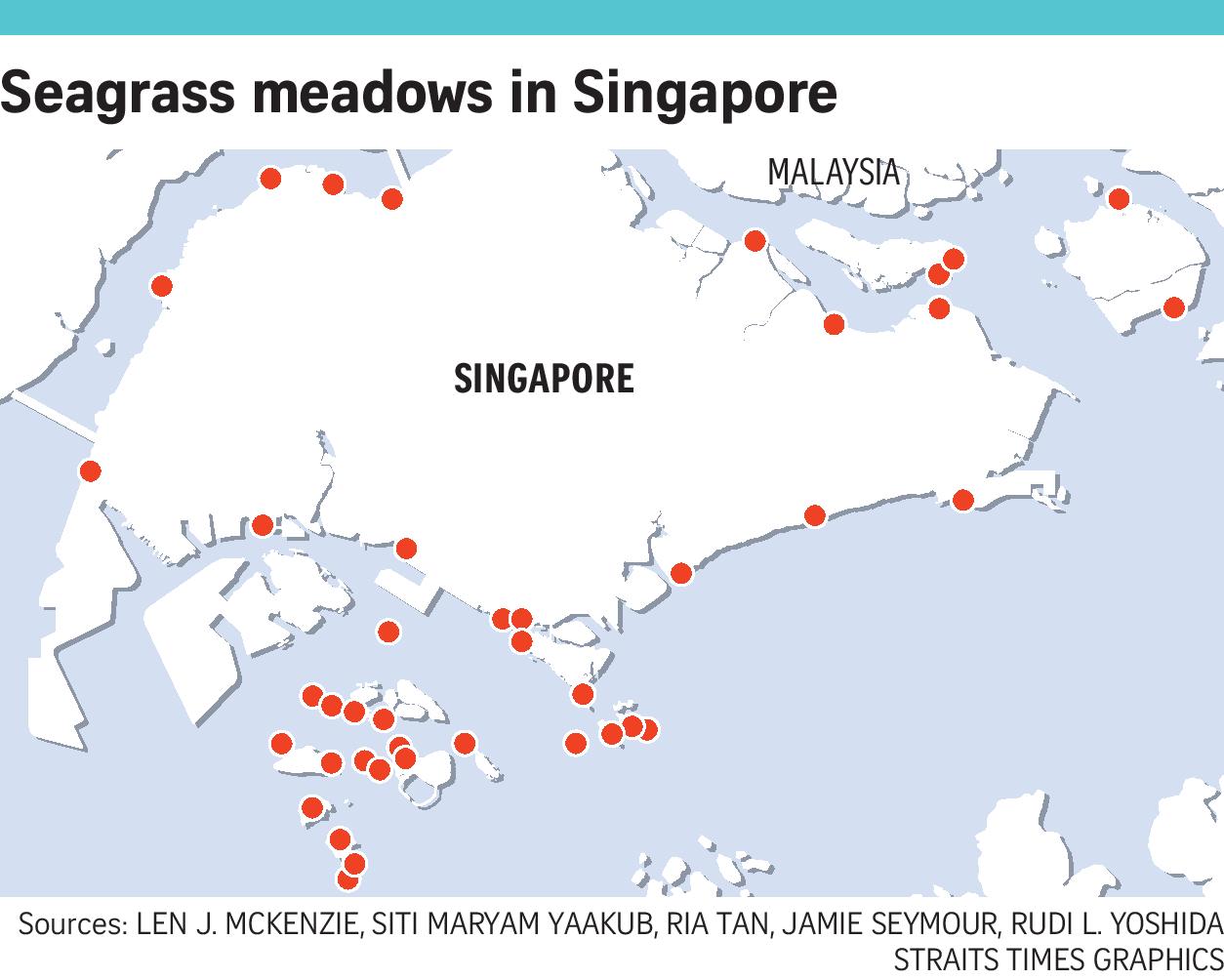

Hidden in the waves, often covered by more colored coral reefs, seagrass meadows dot the coast and ocean all over the country (see map).

Like most of the country’s natural heritage, they have been declining for decades, with about 40 per cent of the original cover lost to coastal development.

According to the National Parks Commission (NParks), Singapore has 12 seagrass varieties, 23 in the Indian Pacific region.

Since 2007, scientists and volunteers regularly monitor their health status.

In addition to their actual investigative work, they often see seagrass producing fruits and flowers.

Dr. Siti Maryam Yaakub, 35, has led a number of trips and said that because Singapore is a tropical country, seagrass should blossom and bear fruit throughout the year.

“We want to see them at almost every low tide.

But about three to four years ago, senior marine ecologists at DHI’s Department of Water and Environment began to notice that most of the flowers and fruits had ceased to exist.

Seagrass populations can grow by cloning themselves, and long-term surveys do see an increase in the size of some grasslands, such as those in Chek Jawa in the Ugan Group.

But Dr. Siti said the clonal growth – if Singapore ‘s seaweed is indeed being done, could mean that all new seagrasses are equally susceptible to stress factors such as disease, making it easier for the entire new population to die at the same time.

In addition, no seeds lying in the environment, new plants more difficult to come back.

Samantha Lai, PhD candidate at the National Laboratory for Marine Ecology at the National University of Singapore (NUS), says there is already one such case in Semakau Island.

In 2009, the island ‘s seagrass meadow suddenly died, and in addition to some of the scattered seaweed, the area was still barren, she said.

Dr Lai said environmental factors were also the culprit, but added that one of the consequences of not having enough sex was “not enough seedlings or seeds to help Semakau recover.”

Dr. Siti described the seagrass research as “very nascent” and acknowledged that there are a lot of researchers who do not understand but they “work hard to fill many of these gaps.”

This is the purpose of their current research, involving NParks in collaboration with the National University and DHI.

Dr. Karenne Tun, Director of NParks National Center for Biodiversity (Coastal and Marine), said that the three-year research project, by mid-2018, aims to better understand the segregation patterns of seagrass and assess how to restore them. For a variety of pressures.

“By assessing the status, connectivity and productivity of seagrass meadows in Singapore, we will be able to develop measures to protect seagrass, including restoration of their habitat.

“We’re just understanding the behavior of the seagrass ticks,” Dr. Siti said.

“Filling these gaps in our knowledge is the best chance for us to ensure that they continue to survive.

josehong@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on Dec 29, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.