SINGAPORE: As they arrived, the guests would have been in no doubt they were attending a high-profile event.

Huge balloons and congratulatory flowers festooned the area. Drummers and a Chinese orchestra revved up the celebratory atmosphere. Photographers clicked away as guests streamed in and warm handshakes were exchanged.

At the centre of it all was Olivia Lum, the founder of home-grown star company Hyflux.

Dressed in a black and white pant suit, the businesswoman, whose name was synonymous with the water treatment giant she built, had a broad smile when the day’s special guest, Singapore’s Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong, arrived.

It was a happy day, as seen from the scenes captured by a video on Youtube.

The event was the opening of Tuaspring desalination plant – Singapore’s second and largest seawater treatment plant supplying 70 million gallons of treated water, or 125 Olympic-sized pools worth of water, per day for 25 years.

It was also the first water plant in Singapore and Asia to be integrated with a power generator.

Costing more than S$1 billion to build, the Tuaspring project marked Hyflux’s foray into the energy business. Even if the power plant was not yet operational in September 2013, Lum was eager to showcase her pet project.

“Today is an especially proud moment for all of us at Hyflux,” she told the guests – who included bankers, analysts, foreign dignitaries and local officials – at the invitation-only event.

The Prime Minister, who gave a speech after Lum, said Tuaspring was the “latest milestone in Singapore’s water journey”.

Amid the high spirits, no one could have guessed that this plant would in a few years’ time take mighty Hyflux from its peak to near rock bottom.

For all the ambitions that it embodied, it struggled to make money. The plan was for the power plant to supply electricity to the desalination facility and sell the excess to the national grid, thereby raising energy efficiency and cut costs. But by the time Tuaspring started feeding electricity to the grid, a severe oversupply in the power generation market had made prices undesirably low.

As losses snowballed, Tuaspring became the “noose” around Hyflux’s neck.

Last May, the listed firm sought court protection to restructure a mounting debt pile of nearly S$3 billion.

Since then, the process has never been far away from the headlines – marked by investor angst that culminated in a rare public protest and a last-minute abortion of a white-knight takeover – and the end seems nowhere in sight, with Hyflux still trying to cobble together a survival plan as this article was being written.

And now, it has ceded control of Tuaspring desalination plant, which opened to much fanfare in 2013, to local authorities on Saturday (May 18) for no money, paralleling how Hyflux has shrunk from one of Singapore’s most successful home-grown businesses to a shadow of its former self.

Prime Minister Lee Hsien Loong was guest of honour for the opening of Tuaspring Desalination Plant on Sep 17, 2013. (Photo: Hyflux/Annual report)

1989-2010

MAKING WAVES

The rise of Hyflux has been told many times, alongside the rags-to-riches story of its founder.

It began in 1989 when Lum left a career in pharmaceuticals and sold her car and apartment to start a business to help solve the world’s water problems.

The indomitable spirit that Lum – an orphan who grew up in a small Malaysian town – displayed in her early life saw her through the tough years of entrepreneurship. By the late 1990s, Lum’s 14-hour work days paid off and Hyflux had made a name for itself with its proprietary membrane technology.

The company went public in early 2001. That year, it also secured its first municipal water treatment project in Singapore to supply and install the process equipment for the country’s first NEWater plant in Bedok.

Other key projects that followed included Singapore’s third NEWater plant in Seletar and the SingSpring Desalination Plant, the country’s first seawater treatment facility. Hyflux also expanded beyond the shores of Singapore, with projects in northern China, India, Algeria and Oman.

Along the way, it garnered state investment firm Temasek Holdings as one of its shareholders, albeit for a brief period from 2003 to 2005.

By 2010, Hyflux was prospering. Its market capitalisation peaked at an eye-popping S$2.1 billion; revenue and net profit also hit record highs of S$569.7 million and S$88.5 million, respectively.

Lum became a role model for entrepreneurs, especially at a time when female founders were comparatively few and far between. She won awards and was at one point a Nominated Member of Parliament.

It was at this peak when Hyflux cast its eyes on its most ambitious project.

READ: Once a star company, Singapore’s Hyflux faces major challenges

READ: Hyflux’s Tuaspring plant: The ‘noose around the neck’ that needs to be sold, but can it be done?

OCT 2010

“IMPOSSIBLY LOW BID”

Four months before, PUB had called a tender for Singapore’s second and largest desalination plant to be built at Tuas.

Lum wanted that for Hyflux, so she engaged consultants and began studying the local power market, according to industry publication Global Water Intelligence.

She drew up a proposal to build a power plant, which she argued would be profitable and allowed for “an impossibly low bid” of supplying water at a first-year price of S$0.45 per cubic metre, the article added.

When the tender closed in October, PUB received nine bids. Hyflux’s submission was way below its competitors, such as S$0.67 per cubic metre from Keppel Seghers and S$1.42 per cubic metre from Sembcorp Utilities.

It was also markedly lower than the first-year price of water for SingSpring Desalination Plant at S$0.78 per cubic metre.

MAR 2011

TUASPRING IN THE BAG, BUT DOUBTS SURFACED

Five months after it submitted the bid, Hyflux was named preferred bidder for Tuaspring. It would be the company’s largest contract to date.

“We showed our mettle by securing Singapore’s second seawater desalination project amidst very tough competition,” its 2011 annual report said.

But while the company saw it as a win, some analysts had their doubts.

Carey Wong, a former analyst who tracked Hyflux since its initial public offering, recalled how questions were asked at an analyst briefing about the company’s move into the energy business.

“When they announced the project, a number of us were quite surprised why they’d even want to go into power … ‘Why are you going out of your comfort zone? Will you have capabilities to do something like this?’ We had some reservations.”

But Hyflux was “very bullish” about the prospects of selling excess electricity and using that to offset its low bid, Wong recounted in an interview with CNA last month.

True enough, Lum said in a Feb 15 affidavit this year that the “technical and financial viability” of the Tuaspring project was “validated and approved by various parties, including regulators, professional advisors and project finance lenders” at that point in time.

“Electricity (trading) prices were about S$200 back then so it had seemed doable. Nobody foresaw the fall in prices,” said Wong, who is now vice president of portfolio management at Ascend Capital Advisors.

“Now when you look back with hindsight, that’s the one that did them in.”

APR 2011

“EVERYONE KNOWS WHO HYFLUX IS”

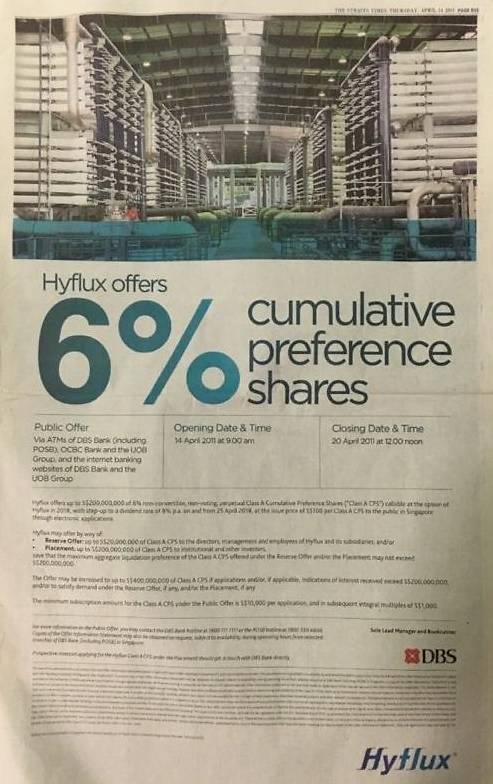

The 25-year water purchase agreement with PUB was signed on Apr 6. To fund the Tuaspring project, the company geared up for the issue of its perpetual preference shares with a 6 per cent annual dividend.

It set up a telephone hotline, held roadshows and placed advertisements in the local newspapers.

Hyflux held roadshows and placed advertisements in major newspapers when it issued its 6 per cent perpetual preference shares in 2011.

The advertisements caught the attention of Max. The then-civil servant had made some money from his holdings in similar instruments offered by local banks, and was mulling new investment opportunities.

“They have to go through the Monetary Authority of Singapore to do these issues. You don’t see the smaller companies issuing these for retail investors so it seemed that only the safe companies are allowed.”

Max, who by then had been investing in the local market for at least a decade, added: “The banks are safe names and everyone knows who Hyflux is.”

Max was not alone. The preference shares, which were then the first non-bank corporate perpetual issue by a Singapore company, saw strong interest and was over-subscribed by about six times, Hyflux said in its 2011 annual report.

A strong brand name aside, there was also the lure of attractive coupons in a low interest-rate environment.

2011 proved to be a momentous year for Hyflux with several milestones.

In July, construction of the Tuaspring integrated plant began. Later in December, Lum became the first Singaporean and the first woman to be crowned the Ernst & Young (EY) World Entrepreneur of the Year award.

An even bigger milestone was to come in 2013.

Hyflux founder-CEO Olivia Lum became the first Singaporean and the first woman to be crowned the Ernst & Young (EY) World Entrepreneur of the Year award in 2011. (Photo: Ernst & Young website)

SEP 2013

“IT WAS A CARNIVAL”

After two years of construction, the Tuaspring desalination plant was finally ready. With the balloons and congratulatory flowers all over the facility, Wong, who was covering Hyflux then as an analyst, recalled the opening.

“It was a carnival,” he said. “Olivia Lum was in good spirits. It was one of their biggest projects.”

But by then, its financial statements were looking less rosy.

Net profit had dropped to nearly half of that in 2010. Operating cash flow, which indicates how much cash is generated from business activities, had been negative since 2010.

That meant the company had to increase its investment cash flow through means such as selling assets, in order to keep its free cash flow positive. Otherwise, it would have to resort to external funding, like issuing shares, bonds or loans.

Nevertheless, the mood at the plant opening was a joyous one.

“While the desalination plant is now completed, our work continues with the onsite power plant. We look forward to its completion and connection to the national energy grid,” said Lum.

2014 TO 2016

CHALLENGES EMERGE

It would take almost two years before that happened.

In May 2014, Hyflux reported its first delay in connecting Tuaspring to the national grid. It only managed to do so in the second half of the following year, and began selling electricity to the grid by Feb 2016.

However, it cautioned in its 2016 annual report that “persistently low electricity prices due to an oversupply are expected to continue impacting near-term profitability”.

At the same time, external challenges, such as plunging crude oil prices and persistent political uncertainty in the Middle East due to the Arab Spring uprisings, added a further squeeze on its profits.

It remained aggressive in borrowing and issued 6 per cent perpetual securities in May 2016. Again, it saw red-hot demand from retail investors and had to upsize the issue from S$300 million to S$500 million. Max, the retail investor with preference shares, was among those that subscribed.

“The strong demand for the securities is testament to the market’s confidence in Hyflux,” Lum was quoted as saying in the company’s annual report.

FEB 2017

EXPLORE DIVESTMENT OF TUASPRING

The fall in electricity prices continued to take a toll on Hyflux’s finances. Eight months after, the first sign of weakness came when Hyflux reported earnings of S$4.8 million for the full year ended Dec 31, 2016 – a steep fall of 91 per cent from the previous year.

The company said weaker-than-expected electricity prices had “substantially wiped out” its profits. Excluding losses from the Tuaspring plant, full year earnings would have been S$118 million.

In line with its asset light strategy, it decided that it would be seeking partial divestment of Tuaspring.

The Tuaspring Integrated Water and Power Plant. (Photo: Hyflux)

Later that year, Hyflux caught the attention of iFast Corp’s senior fixed income analyst Ang Chung Yuh.

“Clearly, the financials are unsustainable,” Ang thought. So he released a report on Sep 6, noting Hyflux as a “negative issuer” with a “highly leveraged” overall financial risk profile.

“Even before accounting for the large amount of perpetual securities outstanding, Hyflux’s balance sheet appears unsustainably stretched by any standards,” Ang wrote.

Corporate perpetuals, like those issued by Hyflux in 2011 and 2016, are bond-like instruments that have no maturity date. As such, local issuers have always viewed them as equity, rather than debt. Even a non-call or non-payment of distribution do not constitute defaults.

On this, Ang said there are different views and he belonged to the camp of analysts who recognized perpetuals as debt.

Hyflux’s debt to earnings before interest depreciation and amortization (EBITDA) was at 13.4 times in 2016, while its debt-to-market capitalisation ratio stood at 3.9 times, his report said.

But if one were to take into account the perpetuals, both indicators would “jump to dizzying levels” of 23.4 times and 6.8 times, respectively. “You don’t have to be an expert to know that (this is) not sustainable,” Ang wrote.

With Hyflux falling short of working capital and liquidity, the analyst said the company would have to turn to selling some of its assets to meet short-term needs, and viewed plans to divest Tuaspring as “potential credit positives”.

The analyst, however, acknowledged in a recent interview with CNA that he had underestimated the challenges Hyflux would face when it came to selling its key asset.

FEB 2018

WARNING SIGN?

The losses of Tuaspring proved to be an obstacle in Hyflux’s search for a buyer.

As that came to nothing in 2017, Hyflux announced its first full-year loss since going public. The Tuaspring integrated plant alone chalked up losses of S$81.9 million.

It also said that it would not be redeeming its S$400 million tranche of preference shares until the partial divestment of Tuaspring was completed.

“That’s no longer just a warning sign,” Ang told CNA last month, noting that a failure to redeem such Sing-dollar-denominated investments “has never happened”.

“For a company with very stretched financials, that means a very precarious situation.”

Ang said he started getting queries about his report released in 2017, and more discussions among analysts emerged about whether Hyflux would be able to sell off its prized asset.

Despite all that, Lum reiterated at a results briefing in February that there were still interested parties and Hyflux would not accept a fire sale below Tuaspring’s book value.

File photo of Tuaspring Desalination Plant. (Photo: Darius Boey)

MAY 2018

“I’M GOING TO LOSE MY INVESTMENT”

On the morning of May 22, a Bloomberg article said Hyflux was eyeing court protection to facilitate negotiations with creditors.

Emails to the company were unanswered until late in the evening, Hyflux confirmed that it had applied to the Singapore High Court to commence a court-supervised debt restructuring and an extended six-month moratorium.

A day earlier, it had suspended trading in its SGX-listed shares and related securities. At its last trade price of S$0.21 a share, the company’s market value of S$165 million was a far cry from its 2010 peak.

The news came as a “big shock” for tens of thousands of Hyflux retail investors.

READ: ‘A big shock’: Retail investors in Singapore caught out by Hyflux woes

“Initially, the financials were good then it deteriorated rapidly within a short span of time. By then, the price of the securities was too low to offload (and) it was due for redemption, so I decided to wait,” said Madam Loo Leung Hun, a retiree who invested in 2,500 preference shares in 2012.

“The first thing that came to my mind (when I saw the news) – I would not receive any interest and I’m going to lose my investment.”

But just two months before, the company’s auditor KPMG had signed off on Hyflux’s audit report.

This would later become a question that some investors had. In a letter to the company’s board on Feb 11 this year, the Securities Investors Association of Singapore (SIAS) asked how KPMG provided the clean audit report and what could have happened during those two months.

In its reply to the investor advocacy group, Hyflux said when KPMG issued its unqualified opinion, “there were no events or conditions that … cast significant doubt on the going concern assumption as at the balance sheet date of Dec 31, 2017, or at the audit report date of Mar 22, 2018.”

ONE YEAR ON, RUNNING DRY?

Just like how investors were baffled at what could have gone wrong in two months, Hyflux’s journey to restructure its mounting debt has left watchers equally bewildered.

By October 2018, it found a “white knight” in Indonesian consortium SM Investments, with whom it inked a S$530 million investment agreement. At the press conference, Lum declared it as “a happy day”.

It was then that developments picked up pace and emotions started running high.

For many retail investors, the offer from SM Investments seemed inadequate given that Hyflux had a debt of nearly S$3 billion.

Worries of steep haircuts among retail investors brewed. By the time the second town hall meeting organised by Hyflux came round in January 2019, updates from the company’s advisors that junior creditors would get nothing in a liquidation scenario only served to fuel these concerns.

“I remembered it was quite dark when I left the Hyflux office (after the town hall). There were people around me; we looked at each other but nobody wanted to talk,” said Max.

“Some of them were holding on to the bento boxes but I didn’t bother. I just wanted to get out of that place. That was when we realised that we would not get our money back. The deal is so bad.”

READ: Commentary: The fall of once-great Hyflux, a unicorn in the Singapore story

READ: Commentary: Hyflux after the perfect storm

True enough, by February 2019 when it laid out its restructuring plan – one that would ask some of its investors to accept as much as a 90 per cent haircut – anxiety turned into anger.

However, before the vote on the plan could take place, things turned south fairly quickly. Hyflux aborted the key crucial rescue plan with SM Investments in April, but not before investors staged a protest at Hong Lim Park and national water agency PUB issued a default notice to Tuaspring.

The U-turn in the deal has left the company hanging by a thread. Since then, Hyflux has managed to convince the Singapore court to grant it another debt moratorium extension, and has announced at least three potential new suitors. However, nothing has been confirmed for now.

READ: Hyflux announces third potential investor, with letter of interest to acquire overseas assets

READ: Hyflux’s UAE investor plans to meet retail investors, asks PUB to delay Tuaspring takeover

One thing is for sure, it has lost control over its key asset with PUB seizing the desalination plant on Saturday.

In a statement, the national water agency said: “To safeguard Singapore’s water security, PUB … will take over Tuaspring Desalination Plant with effect from May 18, 2019, following termination of the water purchase agreement with Tuaspring Pte Ltd.”

Secured lender Maybank has also appointed receivers and managers over the remaining assets of the plant.

Even after seeking court protection in May 2018, Hyflux had continued to paint a rather optimistic picture about divesting Tuaspring. In July, when the management met the media, Lum had said that it was in talks with eight bidders.

It was only until October when there was more clarity. Bloomberg reported that Keppel and Sembcorp Industries were the only parties pre-approved by PUB as potential buyers, and that of the two, only Sembcorp had submitted a final bid.

The fate of Tuaspring being seized at no cost has left investors devastated. In a letter sent by SIAS to PUB in March, the investor watchdog asked how the zero-dollar price was determined.

In PUB’s response, it said the desalination plant purchase price is expected to be negative, based on calculations under the water purchase agreement. It is willing to buy the plant for zero dollars and waive any compensation claims on TPL.

Unsatisfied, a group of retail investors sent another list of questions to PUB last month, requesting more details.

“In Singapore, even the smallest HDB flat cost more than S$0. How can a plant of this size be worth S$0? Can PUB share the company who did the valuation and its basis of the valuation?,” the letter read.

Earlier this week, one of Hyflux’s potential investor Utico made a last minute appeal to the national water agency to seek a delay in the takeover. PUB has responded that the seizure would go on as planned.

For some investors, the past year has been a painful one.

An investor who CNA met at a shareholder’s meeting last year, shared how he had invested in Hyflux over a span of two decades, slowly accumulating his portfolio in the company’s ordinary shares, perpetual securities and preference shares.

He had trusted the company as a well-known brand dealing with an important resource. Altogether, he ploughed in more than S$200,000 of his hard-earned money.

When contacted for this article in April, this investor said he had decided to move on. “It pains me every time it’s being dug up for discussion. This saga has taken a toll on me and my family.”

“After all these months, we have struggled a lot and recently decided to let it be and move on,” he replied via SMS.

But for those who have not, a burning question remains: Will the company they had once pinned their hopes on, be able to move on?