The obsession with grades and exams can take its toll on children. Amelia Teng speaks to experts and shines the light on the pressures children face and what parents can do to ease their burden.

One counsellor recalled how a 13-year-old girl scored 83 marks in mathematics but was scolded by her mother for being careless on one of the questions.

“Her mother told her that she could have scored above 85 had she been more careful,” said Ms Lena Teo, deputy director of therapy and mental wellness services at the Children-At-Risk Empowerment Association Singapore. The girl was referred to her because of anxiety, depression and self-harm.

Then, there was a mother who made her son retake the Primary School Leaving Examinations (PSLE), even though he had passed the first time. “I was shocked,” said Dr Carol Balhetchet, senior director for youth services at the Singapore Children’s Society.

“I couldn’t understand why a parent would put her child through another year of primary school for better grades.”

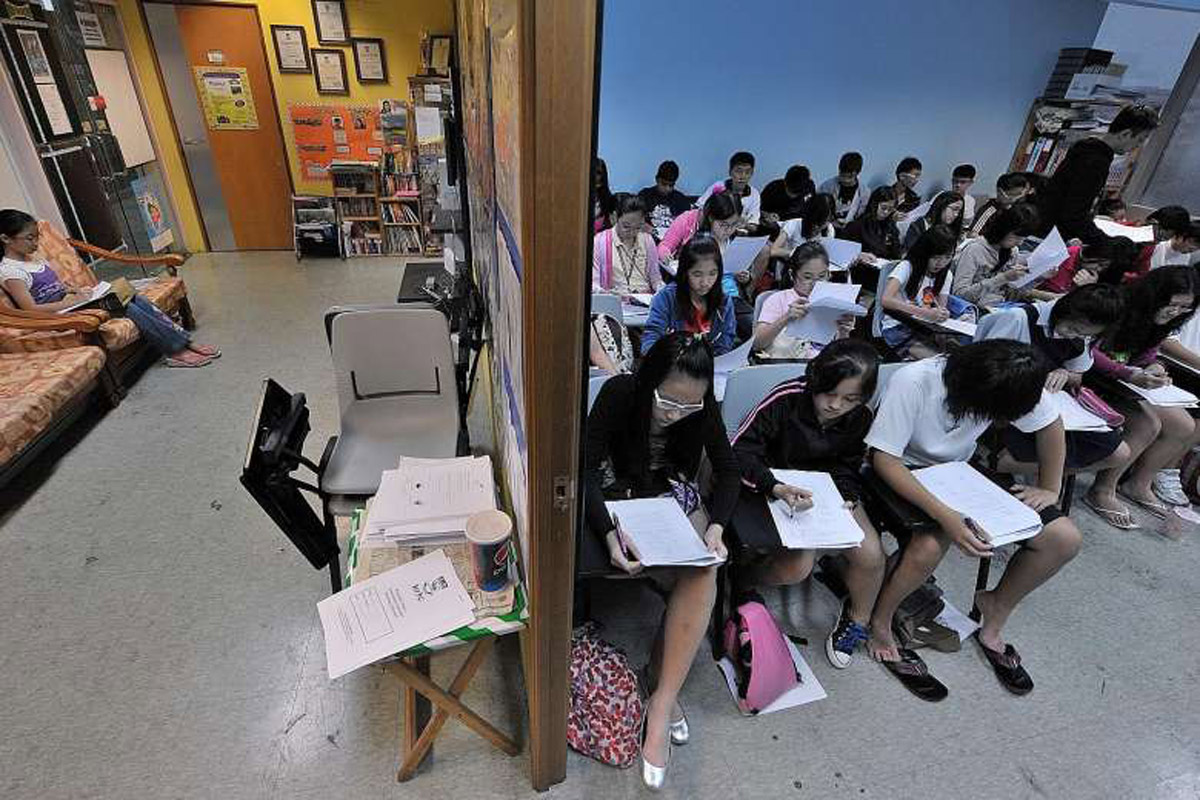

The obsession among some parents for grades and exams is putting undue stress on young children here – an issue that has come under the spotlight after a Primary 5 pupil fell to his death. According to a coroner’s inquiry last week, the boy had seemed afraid of showing his mid-term exam grades, having failed Higher Chinese and mathematics, to his parents.

Parents here have described the episode as a wake-up call, with many admitting it has forced them to rethink how much pressure they put on their young children to do well academically – sometimes without even realising it.

More than As and Bs on a report card, it is the expression on their parents’ faces when they read it that often matters most to children, added experts.

A parent’s show of approval, disappointment or anger are signs of affirmation and acceptance, or otherwise, for young children. “Children just want to see their parents happy for who and what they are,” said Dr Balhetchet.

Latest figures show that last year, there were 27 suicides among 10- to 19-year-olds – a 15-year high. This was double the 2014 figure, despite a drop in the overall number of suicides.

Young suicides have also been on the rise elsewhere – in Britain, 201 young people in the same age group of 10 to 19 had killed themselves in 2014, up from 179 in 2013.

A recent investigation by the University of Manchester of 130 teen suicides also showed that more than a quarter of them had experienced exam stress or other academic pressures.

The worry, counsellors here said, is that parents sometimes do not realise that by harping on grades, young children’s sense of self-worth ends up being defined by how well they do in school. Even the “reminder” that if the child does not do well in school, he could end up with a poor job in the future can add pressure.

Families today also have fewer children, counsellors pointed out. And that means that children not only have fewer siblings to confide in, they also end up having greater expectations placed on them.

Said Madam Madelin Tay from Family Central, a service by Fei Yue Community Services: “With fewer kids, parents can afford better resources and surely want the best for their kids. So it may be intentional or unintentional that they want to see results after investing their time and money.”

And not just when they enter primary school.

Housewife Nadia Ng, 28, who has a four-year-old boy and 2½-year-old girl, said: “Even in pre-school, other parents ask me if I send my son for enrichment classes, but I don’t see a need because he’s so young.”

The Ministry of Education has, in recent years, taken steps to reduce the overemphasis on academic marks, by not naming the top scorers of national examinations and investing more in programmes to nurture students’ strengths in other areas, such as sports or music.

The PSLE T-score – often criticised for causing excessive stress – will also be done away with in 2021, and pupils will no longer be graded relative to their peers.

Mr Bimal Rai, an educational psychologist from Reach Therapy Services, said he sees more efforts to help academically weaker students through schools like Crest Secondary. “The good thing is that there are multiple pathways in the education system today.”

But parents do not buy into this as well – that learning is a lifelong journey.

“There is more understanding across schools that children have to be measured more holistically, but some old structures like grading and assessment haven’t changed,” said Dr Balhetchet.

Mr Brian Poh, a clinical psychologist from the Institute of Mental Health’s department of child and adolescent psychiatry, said that children also have other pressures to deal with. These include friendship issues, bullying, sibling rivalry and difficulties with school authorities, he added.

While some children can cope, counsellors said that others may struggle and later develop socio-emotional problems such as anxiety, extreme mood swings or even withdrawal from social circles.

The Primary 5 boy’s death has seen some parents relook their own behaviour.

Housewife Karen Chen, a 34-year-old mother of three, said: “Education seems like a rat race, and it does seem that kids are under more pressures today. The recent tragedy is a wake-up call for all parents to evaluate ourselves and how we help our kids manage stress.”

Madam Christine Lim, 39, a part-time recruiter who has a son in Primary 2 and daughter in Primary 6, said: “As long as they try their best, I can accept any grade.

“Sometimes I scold them for making careless mistakes or I may threaten to not take them on holidays, but I’ve never hit them for bad results.”

Mrs Tan Kee Leng said she was more careful with her words during the lead-up to her son’s Primary PSLE this year.

“He started to get more stressed and couldn’t sleep very well,” said the 42-year-old who works in a pharmaceutical company.

“Instead of asking him what’s the highest mark or how his friends did… we told him we would accept his results and we would move on no matter what.”

Thoughts of a student on the need to excel

In April 2014, New Zealander Victoria McLeod fell to her death at a Clementi condominium where she lived with her parents.

The 17-year-old who was in her final year in an international school here had put great pressure on herself to get into university, even though her parents had told her that passing exams was not the only way to find her course in life.

Seven months after her death, her parents found her online journal. Here are several extracts:

JAN 14, 2014

Dear Friend,

I lost it. I just sort of keeled over and thought ‘I can’t do this’. Like, I’ve known that I will never have a dazzling life, what with the grades I get. But if I keep carrying on like this, I might actually end up snapping…

I don’t know how I’m going to cope when I get back to school. Will it really help if I ask for it? Would I just be wasting my parents’ money? But the whole point is that I can’t ask for it anyway. How do you explain that you might have social anxiety… I just don’t know. And it scares me.

JAN 15, 2014

Dear Friend; I was out yesterday and saw (). You know, one of those chicks that look like they have it all. Blonde. Lithe. Top grades. Popular. The whole jealously wrapped-up package…

It’s kind of beyond me how someone can have their life so sorted. Maybe I should start comparing them allegorically to filing cabinets. Each file section is a subdivision of life. Academics. Family ties. Extra-curricular activities. Social stature. Looks. Boyfriends/ girlfriends. Socioeconomic state. Mental health. Physical form. With a person like (), not only is every section perfectly organised, but also each page has the right border, font, page number and grammar with A-pluses on each sheet of crisp white paper inside every pastel folder… I gave up on trying to be an () a long ago.

MARCH 30, 2014

I remember something J.K. Rowling wrote in the first Harry Potter book. That there were more important things than Hermione’s affinity with books and cleverness. Like friendship. And bravery. But that’s changing. One day, no one will know the meaning of courage or camaraderie.

Sadly, all that really matters, all that grown-ups are trying to drill into young minds, is success. If you are not successful, there is no point in existence. That’s a pretty sad message to teach. But that is what’s happening, whether we want it to or not.

It doesn’t matter if it’s at the cost of one’s well-being. Even if you were reduced to something barely functioning, but you pulled yourself up and are sitting there, telling your story in an Armani suit, that’s all that matters. That you became a success story.

Marks do fall as lessons get harder but a big drop may indicate other issues

It is common for pupils’ results to dip in upper primary school as they adjust to more subjects and tougher content – and parents need to readjust their expectations.

The introduction of science as the fourth subject at Primary 3 is one factor, but the increasing complexity of concepts being taught also adds to the dip, said educators, who urged parents not to be unduly alarmed. Pupils tend to improve after some practice.

Madam Joyce Ong, 42, said her daughter, now in Secondary 1, had experienced a dip of around 10 marks in mathematics and science when she started Primary 4 and 5.

“As new and more complex topics are added, children might fumble a bit,” said the property agent.

But extra coaching, sometimes through tuition, helped her daugher to catch up, she added. “Some of the problem sums can be quite daunting… I was also unsure which methods to use, so I can imagine it was more difficult for an 11- or 12-year-old.”

However, large drops in scores could point to more serious issues. In the recent coroner’s report into the death of a Primary 5 pupil, it was stated that he had scored 20.5 out of 100 for mathematics and 12 marks for his Higher Chinese exam. For his English language, Chinese language and science papers, he had 50, 53.8 and 57.5 marks respectively.

His principal had testified that the boy had been an “average” student since he started school, and in previous years, had obtained an average of 70 marks for his subjects.

Experts said the huge drop may have meant that the boy was coping with other issues as well.

Several parents also questioned if he should have been allowed to take Higher Chinese as he was an “average” student.

A 51-year-old former primary school teacher said that pupils are given the choice of taking up Higher Chinese at the end of Primary 4 if they do well in the examinations for their languages.

“Schools will also hold briefings after the exams at the end of the year to explain to parents their selection criteria – usually 75 marks and above,” he said.

“Higher Mother Tongue is an optional subject and if, in Primary 5, the pupil fails or is unable to cope, parents can still write in to ask that he or she drops the subject.

“Parents typically like their kids to take a higher language because it looks good on their portfolio.

“But it doesn’t seem very wise for them to continue taking the subject if they don’t do well, even if they qualified for it earlier.”

Key steps in building stronger ties with kids

Speak with them, spend time with them and understand who they are – these, said counsellors and psychologists, are several key steps in building stronger relationships with children, who will in turn be more open about sharing their problems.

Dr Thomas Lee, medical director and consultant psychiatrist at The Resilienz Clinic, said children at the age of 12 and below are still developing emotionally and mentally. He said: “They don’t know how to talk about their feelings.”

Ms Pamela See, an educational and developmental psychologist from Th!nk Psychological Services, said: “If parents are encouraging and allow open communication, their kids are more likely to share their difficulties with them knowing that they will get the support.” Parenting coach Cheren Kwong believes parents must spend quality time with their children, instead of being “too engrossed in work or their phones”.

Psychologist Daniel Koh from Insights Mind Centre explained that communication with children must go beyond what parents deem as “important”, such as if homework is done or they have revised for tests.

Parents must show interest in their children’s lives beyond how they fare in their studies, said counsellor Madelin Tay, from Family Central, a service of Fei Yue Community Services. “If we focus on just the academic aspects, kids may feel accepted only when they have measured up or when they have achieved. Kids want to know that they are accepted unconditionally,” she added.

Dr Carol Balhetchet, senior director for youth services at the Singapore Children’s Society, said: “When children see their parents’ faces, they see a validation of love – whether they come in first or last, whether they win or lose.”

Mr Bimal Rai, an educational psychologist from Reach Therapy Services, said: “Parents need to manage their expectations and be mindful of what they convey to children.

“At the moment, the message that seems to define our culture is ‘you must do well, the Primary School Leaving Examination is very important’.”

Instead, the focus should be on helping children be more resilient when they fail and providing unconditional support.

Said Dr Balhetchet: “We have been brought up with so much success that we think that we cannot afford to fail. But sometimes failure is another way of learning.”

Mr Brian Poh, a clinical psychologist from the Institute of Mental Health’s department of child and adolescent psychiatry, said rather than being overly focused on results, it is better to praise young children for their “effort in completing their work or trying their best”.

Parents and educators can also teach children how to cope with academic pressure, such as setting goals and managing time, he added.

Ms Lena Teo, deputy director of therapy and mental wellness services at the Children-At-Risk Empowerment Association Singapore, urged parents to understand their children’s abilities better: “Every child has (a) different kind of smart. Some are academically smart, some are better with their sports or music, while others are late bloomers.”

Technology entrepreneur Chow Yen Lu, in his 50s, who co-founded Over the Rainbow, a non-profit organisation that promotes mental wellness among young people, said parents need to be less “authoritarian” and more like “partners and advisers”. His lost his own son, Lawrence, in 2009, a few months before his graduation from Murdoch University in Australia. Lawrence had been battling manic depression for eight years.

“The most important thing is to be there, and be supportive… (when facing failure) tell them that it’s like a thunderstorm, that everything will come to pass,” said Mr Chow.

Higher-level schools like junior colleges have started training students in basic counselling skills and mental health issues, realising that it may be be easier for them to talk about their problems with someone of similar age. The Ministry of Education said schools also build resilience in students through ways such as project work, co-curricular activities and camps.

“Teachers teach students social-emotional skills such as time management, goal-setting, coping with stress, and handling expectations,” said a spokesman, explaining that teachers are trained to detect signs of distress and provide basic counselling.

But students at a younger age need more guidance from parents, said counsellors. Part-time recruiter Christine Lim, 39, said she told her Primary 6 daughter, who had read news about the 11-year-old who fell to his death after receiving his Primary 5 results, that after failure, “you can always try again”.

• Additional reporting by Calvin Yang and Yuen Sin

HELPLINES

SAMARITANS OF SINGAPORE (24-hour hotline) 1800-221-4444

TINKLE FRIEND 1800-274-4788

SINGAPORE ASSOCIATION FOR MENTAL HEALTH 1800-283-7019

CARE CORNER COUNSELLING CENTRE (IN MANDARIN) 1800-353-5800

MENTAL HEALTH HELPLINE 6389-2222

AWARE HELPLINE 1800-774-5935

This article was first published on Oct 30, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.