SINGAPORE: Located off Upper East Coast Road, Jalan Hajijah is a quiet road, the home to several condominiums and landed properties.

For most of the last century, however, the area was home to Masjid Kampong Hajijah – a modest mosque serving the 300 residents of Kampong Hajijah, a village that stood by the sea before land reclamation extended the shoreline outwards.

Dating back to 1900, the mosque and the village surrounding it were torn down to make way for newer developments in the mid-1980s.

Independent heritage researcher Sarafian Salleh told CNA that Masjid Kampong Hajijah may have been just one of as many as 120 mosques that dotted the island in the mid-20th century, prior to the establishment of the Mosque Building Fund in 1975.

The mosque and the village were named for Madam Hajijah Cemat, a wealthy Malay landowner who founded the village and mosque, as well as donated the land for nearby Masjid Kampung Siglap, which still stands today.

READ: From Sang Nila Utama to Raffles: Free Telok Blangah tour explores 700 years of Singapore history

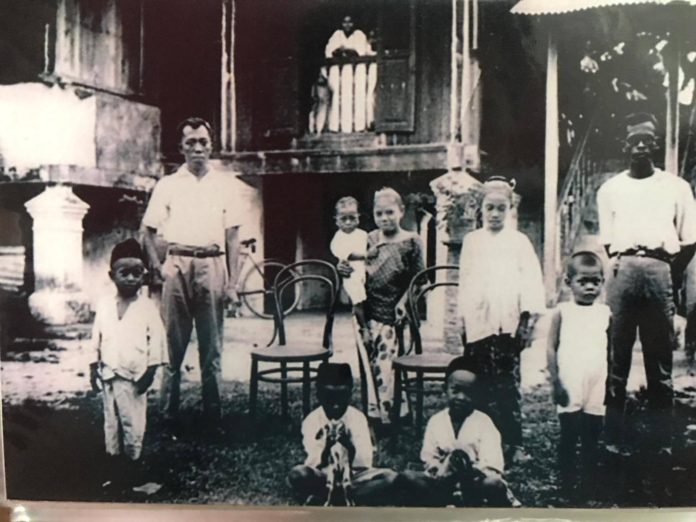

Residents of Kampong Hajijah circa 1986, before the village was redeveloped. (Photo: Sarafian Salleh)

His experience documenting Masjid Kampong Hajijah in 1986, when he was just 16, sparked Mr Sarafian’s passion for heritage photography.

This passion slowly faded after he furthered his studies, got married and had children, he noted.

“The photos that I had amassed over the years were eventually forgotten and lost,” he said.

EVERY MOSQUE HAS A STORY TO TELL

His passion was ignited once again in 2007, when he dug out old photos and started sharing them on social media.

“My postings of old photos of Kampong Hajijah caught the attention of Ms Hanizah Abdul Ghani who was the great-granddaughter of Mdm Hajijah, the lady who built Masjid Hajijah in 1900,” he said.

Ms Hanizah shared stories about her great-grandmother, and this spurred Mr Sarafian to “think that every mosque has a great story to tell”, he added.

The 50-year-old – a mechanical engineer by trade, who also volunteers as a tour guide with non-profit organisation My Community – said the number of such “lost mosques” in Singapore is not well-documented.

Heritage researcher and volunteer tour guide Sarafian Salleh (Photo: Zaili Mohama Din)

However, his own research – together with that of his friend Mr Zaini Kassim – has helped plug this gap, locating and cataloging such forgotten mosques, working with information from archives as well as contributions from friends.

“Mr Zaini Kassim has been consolidating the names of existing and lost mosque in Singapore and we have consistently updated the information on social media,” Mr Sarafian said.

Mr Zaini, 56, said his own work documenting mosques began in the 1980s, when he realised such “kampong mosques” were slowly disappearing.

Mr Zaini noted that one such kampong mosque, Masjid Kampong Holland, closed in 2014 after having been around since the 1950s – first as a surau (small prayer hall) before being upgraded to a 500-congregant mosque in 1975.

Only a handful of kampong mosques remain here, on temporary occupation licences issued by the Singapore Land Authority – such as Masjid Petempatan Melayu Sembawang, nestled away in a forested area on the outskirts of Sembawang, a stone’s throw away from the Johor Straits.

Another is the 68-year-old Masjid Hang Jebat in Queenstown, which sits at the end of a row of colonial era terraced houses on Jalan Hang Jebat, next to where the KTM (Malayan Railway) train tracks ran before services ended nine years ago.

Mr Sarafian and Mr Zaini are not alone.

A Facebook group, called Lost Mosques of Singapore, has about 2,400 members, with almost daily posts on long-gone mosques – such as the Paya Goyang and Angullia Park mosques off Orchard Road, and Masjid Aminah in Geylang, where a block of Housing Board flats now stands.

WATCH: How can Singapore preserve heritage buildings?

The foundation of the two men’s research goes back to a book from the early 1980s entitled Masjid-Masjid di Singapore 1982 (Mosques in Singapore 1982), a slim volume by Syed Abu Bakar Alsagoff which catalogued the mosques in the country at the time.

Despite the “exhaustive documentation” found in the book, the two men, as well as others online, have been able to identify mosques not recorded.

Mr Sarafian hopes to be able to put together a book, documenting the mosques as well as the stories from villagers who used to live around them.

For his part, Mr Zaini hopes more of such books will be written to create a record of mosques and villages that are now forgotten.

With Islam having come to the region centuries ago, Mr Sarafian said mosques here likely predated Masjid Omar Kampong Melaka – built in 1820 by Arab philanthropist Syed Omar Aljunied – which is often acknowledged as the oldest mosque in Singapore, though information about these early mosques have been lost to history.

PRESERVING SINGAPORE’S HISTORY

Mosques of the past were generally found along Singapore’s coastal areas and riverine networks, Mr Sarafian said.

There were mosques found further inland, but these were fewer than those found along coastal areas, he added.

These included Masjid Haji Osman in Seranggong Kechil (now Serangoon), and Masjid Wak Sumang at Kampong Punggol (now Punggol Point), he said, noting various sources point to Kampong Punggol as one of the earliest settlements prior to the arrival of Stamford Raffles.

Named for the Javanese warrior said to have founded Kampong Punggol, Masjid Wak Sumang was demolished in 1995 to make way for developments in the area, though it lives on in the name of an LRT station as well as several roads in the Punggol area.

Masjid Wak Sumang at Punggol Point, circa 1985. (Photo: Sarafian Salleh)

“These mosques were generally constructed in the middle of a Muslim community that lived and traded in the respective district and serve as a place to pray, kampong meetings and teachings of religious knowledge,” said Mr Sarafian.

They often lacked the minarets and domes associated with mosques, he said, and instead the architecture of these houses of worship were designed to adapt to Southeast Asia’s tropical climate.

“These mosques were built on stilts, which allow cross-ventilating breeze beneath the dwelling to cool the space whilst mitigating the effects of the occasional flood,” he noted.

“The roofs were steeply pitched to facilitate storm water and excessively overhung to offer shade and reduce glare from the sun.”

Mr Sarafian added that these mosques were often sited together with community wells, where villagers could draw water to perform wudhu – the Muslim ritual washing before prayer.

READ: Commentary: We can’t save the Sentosa Merlion, but can sure protect other aspects of Singapore’s heritage

A communal well at Masjid Kampong Hajijah. (Photo: Sarafian Salleh)

Older mosques also had percussion instruments called the bedok and the kentong, which were sounded to call residents for the five daily prayers.

These mosques were smaller and often served no more than 300 people each, he said, compared with up to 5,000 worshippers today as with Masjid Darul Ghufran in Tampines.

While newer mosques are generally given Arab names, Mr Sarafian said older mosques had “Malay names”, associated with known personalities or historical locations.

Documenting these forgotten mosques is an important process in preserving Singapore’s history, he said.

“Keeping the original names of the mosques helps to retain the history of the folks living there who were the building blocks of the nation.”