“Champurah”, which sounds like campur or “to mix” in Malay, is part of the dying heritage language of the Portuguese-Eurasian community called Kristang. It is a language spoken by fewer than 500 people across Malacca and Singapore today.

Eurasian-Chinese undergraduate Kevin Martens Wong, 24, has made it his mission to revive the language in Singapore.

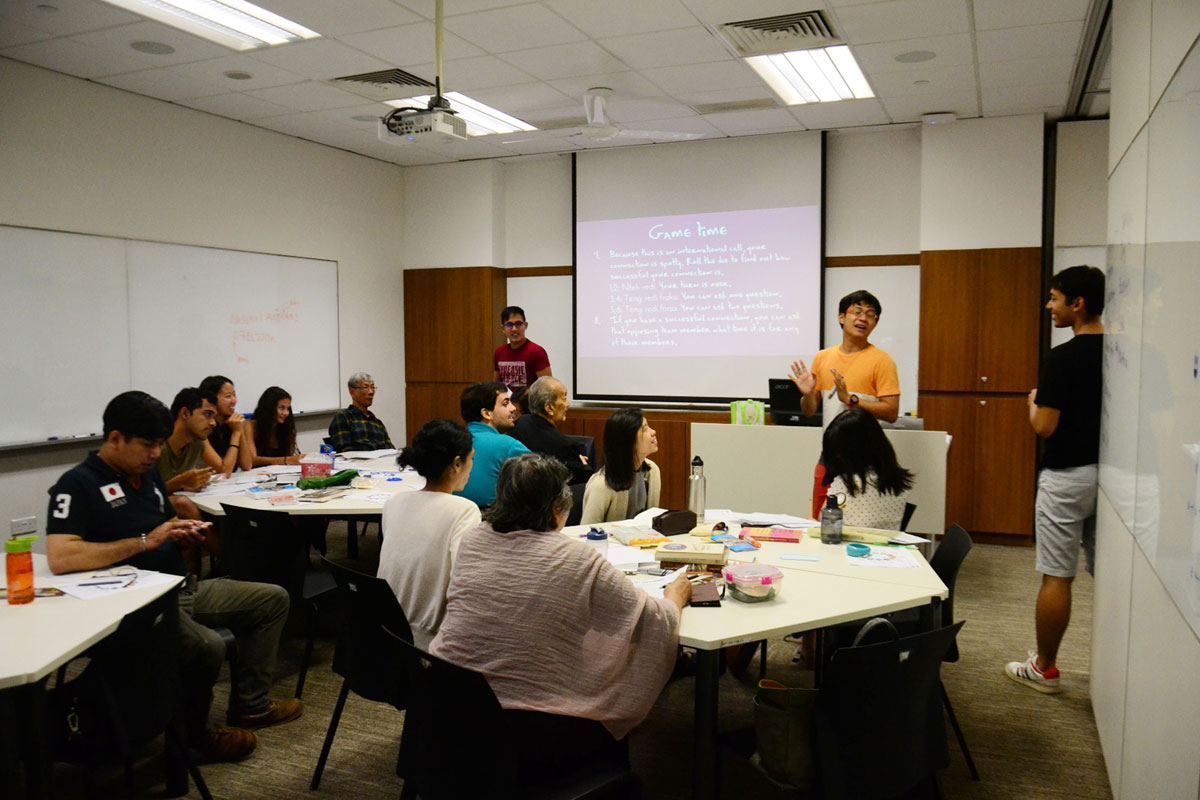

After learning it in two months last year from older Kristang speakers, he developed a curriculum and then started running classes for students this year.

It grew from 14 students in the first term in March to 42 in the second term in July. He now has more than 100 for the current term which started last week.

Mr Wong said the unique language “reflects early Singapore history and the interactions we had”, noting that the lexicon of Kristang is mostly from Portuguese while its grammar is largely rooted in Malay. Kristang also evolved to incorporate dialects such as Hokkien, Hakka and Cantonese.

The language was likely borne out of intermarriage between Portuguese colonisers, who settled in Malacca, and local Malay residents.

In Singapore, it was common to hear it spoken in Katong, Frankel Avenue and Joo Chiat. But by the 1930s, use of Kristang had begun to decline as it was perceived by the community as a broken language.

The English language was adopted instead, partly because it was seen as more desirable and useful for employment in the British civil service.

Mr Wong, whose mother is Eurasian, never heard of the language until he stumbled on it while doing research on endangered regional languages for an online linguistics magazine which he helps to run.

“In my household, like many other Portuguese-Eurasian families, the language stopped with my grandmother. I didn’t realise that some of the food names she used or expressions were actually Kristang words,” he said.

For instance, she refers to the Portuguese-Eurasian dish devil curry as kari debal.

Mr Wong runs the classes with retired primary school teacher, Mr Bernard Mesenas, 78, a Kristang consultant.

His students include Eurasians, and students and faculty members from the National University of Singapore (NUS).

Even his grandparents attend the classes. His grandmother, Mrs Maureen Martens, 80, said the classes helped trigger her memory of some of the Kristang words she learnt from her own grandmother.

Each term comprises 10 lessons that span two hours each, and weekly classes are held at NUS and at the Eurasian Association in Ceylon Road. Students learn for free.

The linguistics undergraduate is doing this on his own time and money although he has received two one-off grants from the National Youth Council and The Awesome Foundation, Singapore.

Mr Wong, who is fluent in German, Spanish and Mandarin, has big plans for Kristang.

He has produced a five-phase, 30-year masterplan to revive the language which includes developing a Kristang textbook by 2019.

Undergraduate Joel Joshua Mathias, 23, a Portuguese-Eurasian who attends the classes, said he is learning Kristang in the hopes of passing it down to his family in the future.

He said: “We should take ownership of our language because if not us, then who?”

melodyz@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on Nov 21, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.