“We once knew a girl named Maria But suddenly that name Will never be the same.”

With apologies to Leonard Bernstein and Stephen Sondheim, whose lyrics I have altered, their enduring love song of the 60s musical West Side Story now seems to have less innocence.

The most famous girl named Maria – Maria Sharapova – may not be all that she seemed.

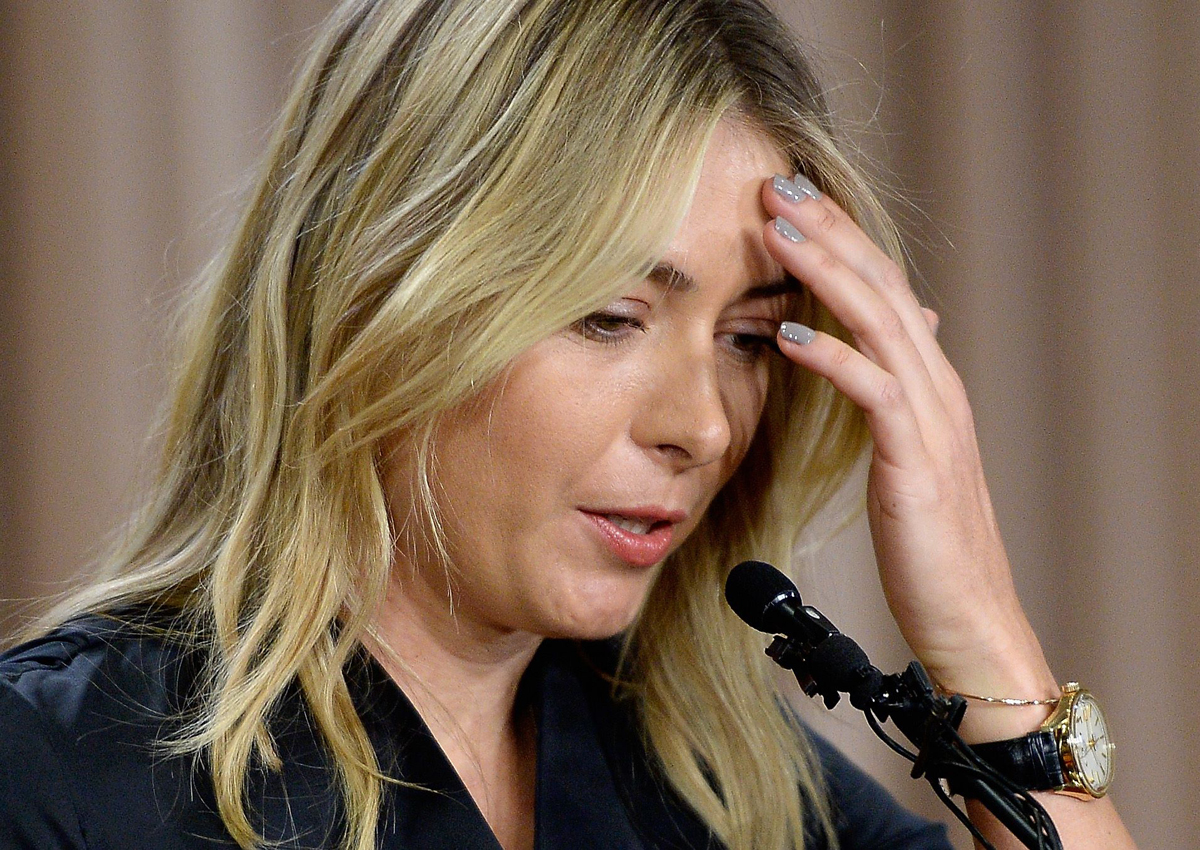

When she donned a widow’s black garb for her press conference in Los Angeles on Monday, it was to pre-empt the announcement by the World Anti-Doping Agency (Wada) that she had tested positive for a banned substance during the Australian Open in January.

“I take full responsibility for it,” Sharapova said, hand quite literally on heart.

“For the past 10 years,” she explained, “I have been given a medicine called mildronate by my family doctor and a few days ago after I received the ITF (International Tennis Federation) letter I found out that it also has another name of meldonium which I did not know.

“It is very important for you to understand that for 10 years this medicine was not on Wada’s banned list and I had legally been taking the medicine for the past 10 years.

“But on Jan 1 the rules had changed and meldonium became a prohibited substance which I had not known. I was given this medicine by my doctor for several health issues that I was having in 2006.”

She knew; but she didn’t know.

Over the past week, the world’s most famous, and richest female tennis player (though not the best; that would be Serena Williams) has divided opinion.

There remain more questions than answers, but Sharapova’s American lawyer, John Haggerty, believes she has a number of “mitigating factors”.

One suggestion was that they might seek a reduction in her inevitable suspension by applying for a retrospective Therapeutic Use Exemption (TUE).

Such exemptions are allowed, and widely applied across many sports. But, obviously, a competitor has to disclose any ailment that might require such medication – and Sharapova had not done so.

Her story during Monday’s (early Tuesday morning Singapore time) press announcement was that she was getting sick very often, that she had a deficiency in magnesium, that she had irregular electrocardiogram (ECG) results, and has a family history of diabetes.

The kind of questions that still need answers would start with just why Sharapova, now 28, was prescribed a Latvian drug by her “family doctor”.

Maria was taken by her father, Yuri, to the Nick Bollettieri academy in Florida when she was just seven years old.

She became one of those tennis prodigies, winning tournaments and big prize money when it was barely legal for a girl to work.

The sheer effort those precocious kids put into their strokes, evident in the accompanying shrieks, have long been a disturbing aspect of this phenomenon.

However, the family doctor mentioned, but not named, may hold some answers. If he or she is American, why was Sharapova prescribed a Latvian drug that is not registered in the US?

And why that particular drug, which the manufacturers say is for Alzheimer’s, angina and serious heart conditions – and generally recommended for use over four to six weeks?

Haggerty later told media that Sharapova has a family history of diabetes and heart conditions, and she was diagnosed in 2006 with asthenia – a lack of energy or strength.

Sharapova had said that she continued taking the medicine while regularly checking the list to ensure that it was not a banned substance.

She had received a letter and an e-mail in December that forewarned athletes that meldonium was being added to the prohibited list from Jan 1.

A rational person might ask why Sharapova missed the warnings that Wada says were repeated five times to all sportsmen and women since last autumn.

We might question not only how she missed it, but also that no one in her entourage was aware of it. Her coach is a Dutchman, her fitness trainer is Japanese, her physio French, her hitting partner is a German male, and both her agent and her legal adviser are Americans.

Those experts are paid out of Sharapova’s estimated wealth of almost US$200 million (S$275 million), and none of them apparently read the list and knew what drugs she has been using for 10 years?

The global reaction also sends mixed signals. Former world No. 1 Caroline Wozniacki, now ranked No. 25, said: “Any time we take any medication, we double and triple-check. Even a thing like cough drops and nasal spray can be on the banned list, so as athletes we make sure not to take something that would put us in a bad situation.”

Yet Sharapova put herself in that situation over an increasingly suspect drug.

Serena Williams praised Sharapova for the way she took responsibility for her actions: “That takes courage and heart.”

However, Nike, TAG Heuer and Porsche, three of her major sponsors, either ended or suspended their deals with her.

Taking the contrary view, the owner of Head, whose rackets Sharapova endorses, took the view that she made “an honest mistake” and, rather than being banned, she should be encouraged to teach tennis to kids over a three-month period of penance.

“I trust what she is saying is the truth,” said Johan Eliasch, the boss of Head. “She says she only received certain dosages and those dosages have been significantly below what would be performance-enhancing.

“I believe she’s been transparent about it – and if she hasn’t, then my reasoning fails.” One man who still thinks of Maria as the most beautiful word he ever heard.

stsports@sph.com.sg

This article was first published on March 12, 2016.

Get a copy of The Straits Times or go to straitstimes.com for more stories.